FORTUNE -- Two years ago this month, Wal-Mart CEO Mike Duke dropped a bomb on the retailing world by announcing that the company would spearhead an audacious effort to create a "sustainability index" that would reassure the environmental and social impact of every product sold in its stores. Though the move was generally praised by environmentalists, Wal-Mart had not suddenly turned green -- it turns out a vast amount of money is to be made by reducing energy and waste up and down the supply chain. As the world's largest company, Wal-Mart had the clout to enforce its implied threat, later made explicit by Duke's lieutenants: Treat the planet well and get prime access to its 200 million customers each week; pollute and despoil, and you will be shunned.

It makes sense to try to measure the impact manufacturers and retailers have on the planet as the world's natural resources come up against the reality of population growth. But can it be done? Clearly Wal-Mart (WMT, Fortune 500) -- which had set a five-year timetable for the index -- had no idea how difficult the job would be. First it spent $5 million creating a group called the Sustainability Consortium (TSC) with Arizona State University and the University of Arkansas, but it took nearly two years to name an executive director. To date, TSC has closely examined only seven products ranging from laptops to orange juice. Though Duke made it clear that "it is not our goal to create or own this index," many of Wal-Mart's competitors, like Target (TGT, Fortune 500) and Costco (COST, Fortune 500), have declined to participate. Major brands such as Pepsi (PE), Dell (DELL, Fortune 500), and Procter & Gamble (PG, Fortune 500) did get on board -- what choice did they have, really? -- but some balked at Wal-Mart's call to create product labels that could blaze from the shelf like a scarlet letter. "So much has to go into a sustainability score and there are so many variables, the question is whether you can come up with a number that's accurate enough to drive meaningful decisions," says Len Sauers, P&G's vice president of global sustainability.

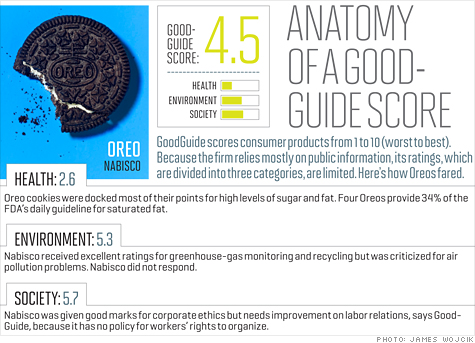

Wal-Mart is certainly not the only one trying to create a sustainability index. San Francisco startup GoodGuide has a useful -- if imperfect -- system that mostly employs publicly available data to rank consumer products. (See its Oreo rating at the top of the page). The apparel industry announced a similar effort earlier this year -- but all face the same daunting obstacles.

The trouble with any consumer scoring systems is that ultimately consumption is about trade-offs. All products -- no matter how "green" -- impact the planet in some way. The best a consumer index can do is suggest that one product in some particular way might have less of an impact on the planet than another. To achieve this, mountains of data have to be gathered about the impact of thousands of products across every stage of their life cycle, from raw materials and manufacturing to final disposal, while including social factors like workplace conditions. How much waste was generated by the factory in rural China that made that zipper? How much phosphate was used to make this laundry detergent? Were the chips in that Blu-ray disc player manufactured in an energy-efficient way?

It gets even more complicated once such data are obtained: How should various forms of sustainability be ranked? Is soil erosion less important than carbon emissions? Gary Hirshberg, founder and CEO of Stonyfield Farm, now a subsidiary of the food giant Dannon, has been trying to measure the impact of his own organic yogurt products since the early '90s. "I'm not saying it's impossible," he argues, "but it's very difficult to do in a credible way."

No wonder Wal-Mart is now backpedaling from its pledge to help create a scoring system for consumers. Two years ago, Matt Kistler, the officer then in charge of the company's sustainability efforts, spoke publicly about the possibility of a number from 1 to 10 or a color-coding scheme. At the same time, the company announced the goal of a "simple rating." Today, Kistler's successor, Andrea Thomas, will say only: "By 2014, consumers will have more information about the sustainability of products they buy."

It's enough to make you wonder whether creating a sustainability index is even worth the Herculean effort. Hirshberg thinks not. A company, for example, might earn high marks for using recyclable packaging, but Hirshberg found that Stonyfield reduced its carbon footprint more by switching to yogurt cups that aren't recycled. It turns out that cups made from plants and then thrown into landfills generate far fewer greenhouse gas emissions than recycled plastic containers. Similarly, a yogurt company might score high for using organically fed dairy cows, but Hirshberg found that a significant source of his company's methane emissions -- a potent greenhouse gas -- is cow burps, of all things. (Stonyfield is in the process of reducing those emissions by tinkering with the feed.)

"In the end we realized that to get a real score is a very costly, complex process that's probably not worth it," Hirshberg says. Instead he founded a nonprofit, Climate Counts, that does not rate individual products but scores the world's largest companies on their commitment to fighting global warming and the transparency of their sustainability efforts.

Another pioneer in measuring sustainability, Yvon Chouinard's outdoor-apparel company Patagonia, also found its well-meaning assumptions turned upside down. Chouinard, an avid mountain climber, founded Patagonia in 1972 and has been a leading apostle of corporate sustainability ever since. But when his company began assessing the environmental impact of its fibers in the early '90s, it found that the most harmful was cotton -- not petroleum-based synthetics -- because of pesticide use. So it switched to organic cotton and helped other companies like Nike (NKE, Fortune 500), Timberland (TBL), and Wal-Mart do the same. But even organic cotton uses an enormous amount of water. By one estimate, a single pair of jeans requires 1,200 gallons of water to manufacture, making the process of trying to eliminate all harmful effects of a product like playing Whac-A-Mole.

Chouinard, however, is not giving up. In 2007, Patagonia joined an effort by the Outdoor Industry Association to create the "Eco Index," a standard for measuring sustainability now being adopted by the clothing and footwear industry through the Sustainable Apparel Coalition (SAC), formed in March. The new indexing tool will help designers select green materials and suppliers based on various sustainability factors. The coalition has postponed any decision about whether it will create a consumer-facing score, the move that raised concerns among Wal-Mart's suppliers.

Rick Ridgeway, a Patagonia executive who is chairman of the apparel group, was a climber in the Chouinard mold -- he was on the first team to reach the summit of K2 without oxygen. Now he wants to help other industries adapt the apparel index for their own sectors. Just imagine: the beer index! The auto index! The toy index! The SAC has attracted clothing makers (Gap (GPS, Fortune 500), Levi Strauss), nonprofits (the Environmental Defense Fund), the U.S. government (EPA), and retailers like J.C. Penney (JCP, Fortune 500) and Target that have spurned Wal-Mart's invitation to join its consortium. "We looked at the Sustainability Consortium for a year and a half," says Tony Heredia, Target's vice president of compliance in Canada, who was VP of corporate risk and responsibility at the time, "but we found other coalitions more aligned with our business strategy."

The SAC faces a steep climb. Few sectors are as opaque as the clothing industry because of its reliance on overseas manufacturers that often don't have a clue where raw materials come from. The Chinese manufacturer of a jacket sold by Bloomingdale's probably used a series of middlemen to buy the fabric, thread, buttons, and zippers, and asked few questions about their origins. The fabric company, meanwhile, may not know the source of the fibers or finishing chemicals it uses. Further down the supply chain, finishing agents that might make a garment wrinkle-free or extra soft are often a mixture of several chemicals that each come from a different set of suppliers.

Perhaps it goes without saying that many companies in the developing world are unfamiliar with the term "corporate sustainability policy." When Hank Paulson was U.S. Treasury Secretary, he says, he asked the manager of a Chinese factory about his pollution controls. The man pointed to a field next to a factory that was belching smoke and said, "See those two camels and a goat? When they fall over from the pollution, we turn off the factory."

Digging deeply into supply chains is so difficult, in fact, than even some environmental groups don't have much hope that a sustainability index will push firms to invest in the staffing and expense it requires. "I hope it will, but the skeptic in me doubts it," says Linda Greer of the Natural Resources Defense Council. Instead she urges companies to join the NRDC's "Clean by Design" program, which offers a series of best practices to help textile mills reduce water, energy, and chemical use, and improve manufacturing efficiency -- all measures she says will pay for themselves in less than a year. Major retailers such as Wal-Mart, Target, and H&M have signed up. "It's not an index of a million things or a score," says Greer. "It's just the simple idea that if companies really care about sustainability, they need to know what's going on in environmental hot spots of their supply chains."

Jason Clay, a senior vice president at the World Wildlife Fund, agrees. He believes that trying to parse the differences among thousands of products is a waste of energy and distracts from the crucial task of corporations trying to design their operations to be as sustainable as possible. "A sustainability index should only exist to help manufacturers put sustainable brands on the shelves," he says.

But how are consumers supposed to know which products may be better for the planet? GoodGuide is trying to assist them by rating over 100,000 consumer items. The company was started in 2007 by Dara O'Rourke, a supply-chain expert and professor at the University of California at Berkeley, when he realized that he had no idea what chemicals were in the sunscreen he was using on his young daughter's face. He did some research and found it contained an endocrine disrupter, two skin irritants, and, most shockingly, a suspected carcinogen activated by sunlight. Investigations of soaps and toys in his house revealed similar hazards.

Today GoodGuide's website rates products on a scale of 1 to 10 and offers a mobile app where you swipe a product's bar code at the store to get those ratings. Shoppers can make decisions based on scores for three major subcategories -- health, environment, and "society" (labor and human rights) -- and search only for products that, for example, are organic, vegan, low in sodium, and not tested on animals.

GoodGuide is small -- it has just 26 employees and has raised $9.2 million in venture capital -- but O'Rourke has assembled a team of life-cycle specialists, engineers, chemists, and nutritionists who mine data from over 1,000 sources, including company disclosures, government agencies, research firms, environmental groups, academia, and the media. Its revenue comes from a percentage of sales from online stores such as Amazon (AMZN, Fortune 500) when users click through, and soon, it hopes, from a version it will offer retailers like Wal-Mart to use for their own buying decisions.

But any scoring system is only as good as the data behind it, and O'Rourke concedes that GoodGuide is only about halfway to information nirvana, if such a state exists, of a verifiable life-cycle assessment of every product. There's much the firm doesn't know about products either because the manufacturers won't say or don't know themselves. GoodGuide won't even rate clothing and footwear because the data are so thin. Still, he insists, we can't wait until academics at places like the Sustainability Consortium perfect the science. "It can take you five years to do a risk assessment of one chemical," says O'Rourke. "We're taking what we believe is the best available science and getting it out to consumers right away."

It's easy to understand the urgency felt by O'Rourke and others. The world's population is expected to grow from today's 7 billion to 9 billion by 2050, offering a mother lode of potential new customers for ambitious companies like Wal-Mart. But "if our environmental demands continue at the same rate, we will need the equivalent of two planets to maintain our standard of living in another 25 years."

By the way, that was Wal-Mart's CEO talking, not some environmental activist. Such dire predictions are why Duke was applauded for calling for a sustainability index. Now he has to figure out how to make one work.

--Paul Keegan is a contributing writer for Fortune and Money. Additional reporting by Josh Dawsey and Betsy Feldman