FORTUNE -- In 2008, Mitt Romney wrote a New York Times op-ed titled "Let Detroit Go Bankrupt." He argued then that if the auto companies got a bailout, "you can kiss the American automotive industry goodbye." Lately, however, the Republican frontrunner has begun to favorably compare the government-imposed structured bankruptcies to his work at Bain Capital. "What the president has done overseeing GM and Chrysler has been reminiscent of what people in the private equity industry do," he said a few days ago in South Carolina. "To try and save the business, you have to cut back to a core that matches the revenue of the business."

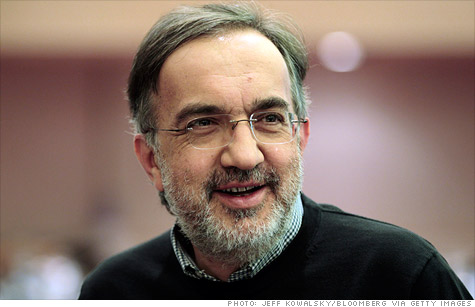

In fact, the restructured Chrysler is expected to report a net profit for the first time since 2006 when it releases its full-year results on Feb. 1. And it is not unfair to give the lion's share of the credit to one man: Fiat-Chrysler CEO Sergio Marchionne. With his lightning-quick mind, boundless energy, and utter self-confidence, he took over the company, selected a management team, created a product plan, and established a set of performance targets. Chrysler's ability to hit them was a huge surprise to industry watchers who still don't have a clear idea of how he pulled it off.

For insight, they need only look back at Marchionne's turnaround at Fiat, when he made the Italian automaker profitable for the first time six years and extracted $2 billion from a cash-strapped GM (GM, Fortune 500) in the process.

New insight into Marchionne's methods are the core of a new book by the Wall Street Journal's longtime Rome bureau chief Jennifer Clark, Mondo Agnelli: Fiat, Chrysler, and the Power of a Dynasty.

An accountant and lawyer by training and a corporate manager by experience, Marchionne had no auto industry experience when the Agnelli family picked him to save the failing Fiat in 2004. As he would later do at Chrysler, Marchionne took matters into his own hands. He selected his own management team after months of walking around at the company, looking for energetic risk-takers and evaluating them on the spot. After picking his team, he sent 2,000 of his rejects off to early retirement.

Clark relates how Marchionne's next step was to put all of his executives together in one room to come up with a business plan. Having wiped out several layers of management, he now eliminated time-killing committees, replacing them with a Group Executive Council to bring together disparate operations like tractors and trucks. Then he formed a 24-person team to run Fiat Auto. The idea was to make Fiat quicker and more efficient by getting all parts of the company to talk to one another. Under the old system, Fiat's three brands -- Fiat, Alfa Romeo, and Lancia -- were run as separate business units that did their own hiring, purchasing, and engineering. "They didn't even share one screw," Clark quotes one engineer as saying. It was if the 1990s had never happened.

Just as deadly was Fiat's practice of putting car development entirely in the hands of engineers. When the engineers were done, they would throw the car "over the wall" to sales and marketing teams with instructions on how many to sell and at what price, Clark notes. It was a process that was guaranteed to be inefficient and to create disputes between different parts of the company.

The new life under Marchionne wasn't easy. Management committee meetings were often held on weekends, and on-the-spot firings were not unheard of. After one manager patted himself on the back for turning a big loss into a smaller one, Marchionne went after him. "I don't need people in here who are happy to lose money," Clark quotes him as saying. "I want people who culturally are all about making money. You are free to go."

Clark describes Marchionne as a world-class poker player, able to keep track of every card in the deck even while carrying on a conversation. He demonstrated his skill at bluffing in winning a $2 billion pot from GM. As part of an alliance between the two automakers in 2000, Fiat had wangled a put option that gave it the right to sell 90% of Fiat Auto back to GM. As the time approached when Fiat could trigger the option, it was still losing money, and GM wanted no part of the company at any price. GM was betting that Fiat would back down because letting itself fall into the hands of an American company would be political suicide. Marchionne called GM's bluff. He asked for a $2 billion settlement in lieu of a lawsuit.

In 2005, Marchionne flew to New York for a crucial weekend meeting to negotiate the settlement with then GM CEO Rick Wagoner and GM's lawyers. Marchionne's bluff worked, and he got his cash. GM would rather pay the money than discover if he was serious about letting Fiat go. Wagoner's mind may have been elsewhere, Clark reports. Before the meeting started, the GM CEO, a former Duke University basketball player, asked for a television so he could follow a big game between his alma mater and Maryland.

Marchionne demonstrated his steely nerve again in his dealings with the government to acquire Chrysler. He badly wanted Chrysler to add some critical bulk and scale to Fiat, but he was short of cash and didn't want to pay for it. The government, represented by Steve Rattner and Ron Bloom, were wedded to the concept of "skin in the game," and were determined that Fiat invest at least a symbolic amount. They didn't want Fiat to walk away from the deal after a few months without any risk if it didn't like what it found.

Marchionne knew that without Fiat, Chrysler would go bankrupt, so he played hardball. "This thing is broken and there is one person who can fix it, and he is telling you now 'I am not paying cash.'" When Rattner insisted that Fiat make a token investment, Marchionne replied, " I don't want to talk about 'skin in the game." I have plenty of it. We are contributing Fiat's technology. And me and my people are going to move over to Detroit and pour our lifeblood into the company."

Fueled by coffee and nicotine, and operating on four hours of sleep a night, Marchionne has done just that. He spends ten days a month in Michigan meeting with his hand-picked team of direct reports in person, and stays in contact the rest of the time by Blackberry. He still makes snap decisions, still works from an aggressive plan, and still fires people who don't fit his definition of "team player. "

Perhaps his most defining characteristic is his unwillingness to sugarcoat reality. When the Fiat 500 failed to hit the 2011 sales targets Marchionne set for it, he personally took the blame for launching the car too soon. Of course, he also allowed the person he put in charge of Fiat to resign, indicating he thought there was plenty of blame to go around.

Understanding Marchionne is critical to understanding the future of the American and European auto industries. Clark goes further than other journalists writing in English in doing that. A few days ago, Marchionne publicly mused about forming "a second Volkswagen group" as part of an industry consolidation. If he goes ahead, let's hope Jennifer Clark is along for the ride to tell his story. ![]()