Deflation warning bells ring louder

Consumer prices may fall on an annual basis for the first time in more than 50 years. Is this the beginning of a deflationary spiral or just a blip?

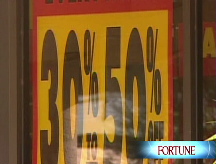

NEW YORK (CNNMoney.com) -- Prices are falling for just about everything these days.

The government will report its key inflation index Friday morning, the Consumer Price Index, and economists believe the report is likely to show the first year-over-year drop in prices since 1955.

But while shoppers might see that as good news, economists generally view this as a threat to an already struggling economy.

That's because deflation, or a widespread drop in prices, is one of the most destructive forces that can hit an economy.

Lower prices are one way businesses respond to the lack of demand for their products in a slowdown. But if companies can't make a profit selling their products at the lower price, they'll respond by cutting production and laying off more people.

More job losses can cut even further into demand. But even if consumers have jobs and money, they're likely to hold off on purchases if they come to believe that prices will head even lower. All of which adds up to even more weakness in the economy.

Deflation is most often associated with the Great Depression. In 1930, consumer prices fell 2.3% and plunged 9% a year later. Prices fell nearly 10% in 1932 before the rate of decline started to slow. Still, prices didn't turn higher again until 1934.

The U.S. is nowhere close to that type of deflationary spiral just yet. Economists forecast that the year-over-year drop in January was just 0.1%

Much of that decline has been driven by lower gas prices. But there is clear evidence that falling prices are spreading beyond the pump. The core CPI, which strips out food and energy prices, fell at a compounded annual rate of 0.3% in the fourth quarter of 2008.

The potential economic pain that can be caused by deflation is so great that St. Louis Federal Reserve President James Bullard identified it in a speech Tuesday as the greatest risk facing the economy this year.

"I think we face some risk -- at this point only a risk -- of sustained deflation," he said, adding that "ongoing deflation in the United States might be particularly pernicious."

Some economists agree that deflation should now be a major concern.

"I think we're on the precipice of outright, full-blown deflation and that we'll fall into that abyss by this summer," said Mark Zandi, chief economist for Moody's Economy.com. "Given the pressures businesses are under to sell something, they'll have to cut prices and I think they will."

Zandi said his biggest worry about deflation is that it may cause more employers to cut wages, which could lead to even lower prices down the road.

Some companies have already begun to reduce salaries. General Motors (GM, Fortune 500) is cutting the pay of all of its remaining U.S. salaried staff between 3% and 10% as of May 1.

"Right now millions of people are losing their jobs, and as painful as that is, it affects only a small fraction of 150 million workers," Zandi said. "If you're cutting wages broadly across 150 million people, that's a far bigger problem for the economy."

But other economists argue that falling prices are not a significant threat to the economy.

They point out that consumer prices fell in the mid-1950's, a relative period of prosperity. And they add that the current drop in prices may simply be a temporary decline due to an adjustment between supply and demand.

"To have deflation, you have to have the price structure collapsing," said Rich Yamarone, director of economic research at Argus Research.

"Disinflation is the D word we should be using," he added, meaning that he thinks prices won't rise dramatically going forward as opposed to continuing to fall.

Yamarone says the steps taken by the Federal Reserve and Treasury to pump trillions into the nation's banking system will keep deflation from taking hold the way it did during the Great Depression and in Japan's "lost decade" that started in the 1990's.

"Those policymakers did nothing for decades," he said. "We're throwing everything imaginable and several things that are unimaginable at the problem."

But Yamarone concedes that prices for many products will be kept in check for awhile, partly because of weak demand in the near-term and demographic changes in the longer term.

"There is too much capacity for everything right now - too many malls, too many auto plants," he said "The Boomers are in the process of retiring and 60-year old Boomers don't need 2.5 cars in the driveway." ![]()