When you're only earning $29,000 a year, getting your paycheck slashed by $400 a month can be financially devastating.

That's the situation 34-year-old Natasha Small is in.

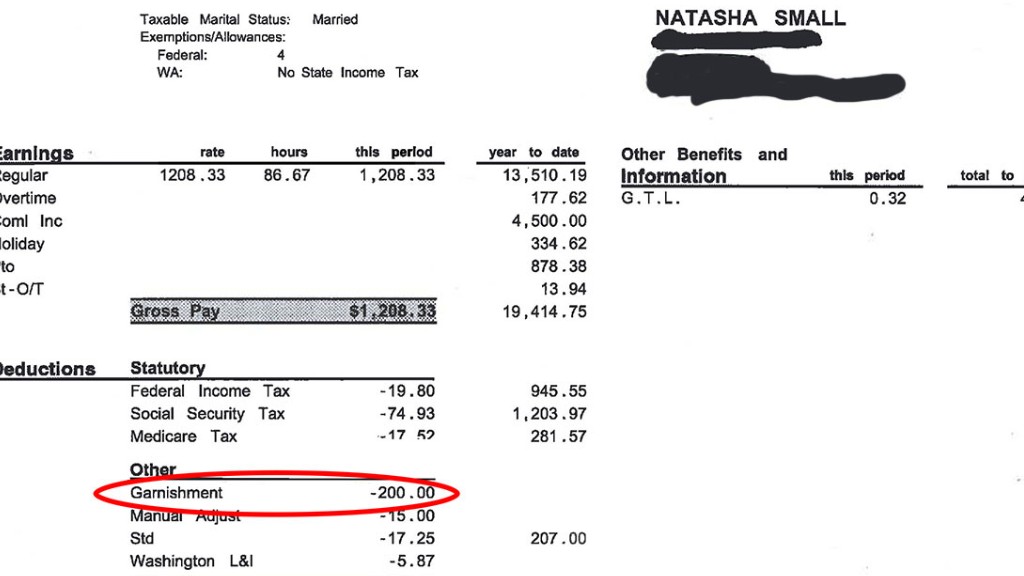

After being laid off by a law firm in 2009, Small finally found a full-time job last spring as a debt collector. But a few weeks in, she was told by an HR person that the state of Washington had garnished her wages by $400 a month.

Why?

A few years earlier, the state said it had overpaid Small $11,000 in unemployment benefits.

Related: What to do if your paycheck is garnished

The two sides don't agree about what happened. Washington state's Employment Security Department, which is in charge of administering benefits, says Small was at fault because she reported that she was earning no income when she had worked two temporary jobs.

Small said those jobs lasted for 30 and 60 days and that she reported every cent she received but continued receiving the benefits.

But in the end it doesn't matter -- the state wants its money back.

Related: Retirees' Social Security checks garnished for student loans

Small was able to pay back $500, and another $6,400 was taken from her tax refunds. But that still leaves over $3,000, some of which is interest.

So Small, who has two teens, has had her monthly pay (after taxes) cut from $2,100 a month to about $1,700.

Making that stretch is very hard: Rent, ($1,050), utilities ($100 to $174) and gas for the family car ($200) leave about $300 a month for food. And four mouths to feed.

Fortunately, her husband, after being out of work, just found a warehouse job that will bring in an extra $15 an hour. But he won't get his first paycheck for another couple of weeks.

The family has canceled cable TV and downgraded to the cheapest Internet service they could find. No one has a cell phone -- just a home phone they qualified for through a financial assistance program.

Related: Hey Occupy Wall Street, abolish my debt too!

"Having that $400 back would do wonders," she said. "I wouldn't have to worry how my kids are eating, and if my kids need new shoes I could get them new shoes and I wouldn't have to worry that I would be taking that money from some other necessity."

And Small is just one of millions of Americans being hit with wage garnishments.

More than 7% of workers nationwide had their wages garnished last year, according to a report from payroll processor ADP conducted as part of an investigation by ProPublica and NPR.

The rate was highest -- at 10% -- among people earning between $25,000 and $39,999 per year.

More than 40% of garnishments are for child support payments. Tax debts make up about 20%, and the rest are for other consumer debts like Small's.

To garnish someone's wages, the entity collecting the debt -- which can be a government agency, a company or private debt collector -- must sue the consumer and get a court order.

Garnishment is typically a last resort for creditors, after consumers stop paying their debts or default entirely. There are some limits under federal law. No more than 25% of disposable earnings can be seized, for example.

But beyond that, states pretty much determine their own policies, said U.S. Labor Department spokesman Jason Kuruvilla.

"Unfortunately some states can be more strict than others," he said.

For Small, who says she can't keep up with the rent and is on the brink of being evicted, filing bankruptcy seems to be the only way out.

"I was trying to avoid bankruptcy, but finally I just couldn't breathe," she said. "I don't have any option right now but to run from my debt, because if I don't, my kids will be homeless again. And I'm not letting that happen."