After just days in office, Greece's new government has begun wrestling with Europe, while inching closer to a more volatile power: Russia.

The countries have a long history of economic, cultural and religious ties. Both are now proving to be a big headache for the European Union.

Greece's government, led by left-wing party Syriza, has started to unpick reforms that were crucial to securing €240 billion ($272 billion) in European and IMF funds keeping the country afloat. Relations between Russia and the EU are the worst they've been since the Cold War due to the Ukraine crisis.

Congratulating Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras on his victory, Russian President Vladimir Putin said he was confident the two countries would "work together effectively to resolve current European and global problems."

Greece seems receptive to closer links. Tsipras reportedly met with the Russian ambassador hours after taking office, and with Russian officials last May.

Related: Europe to Russia: We won't blink over Ukraine

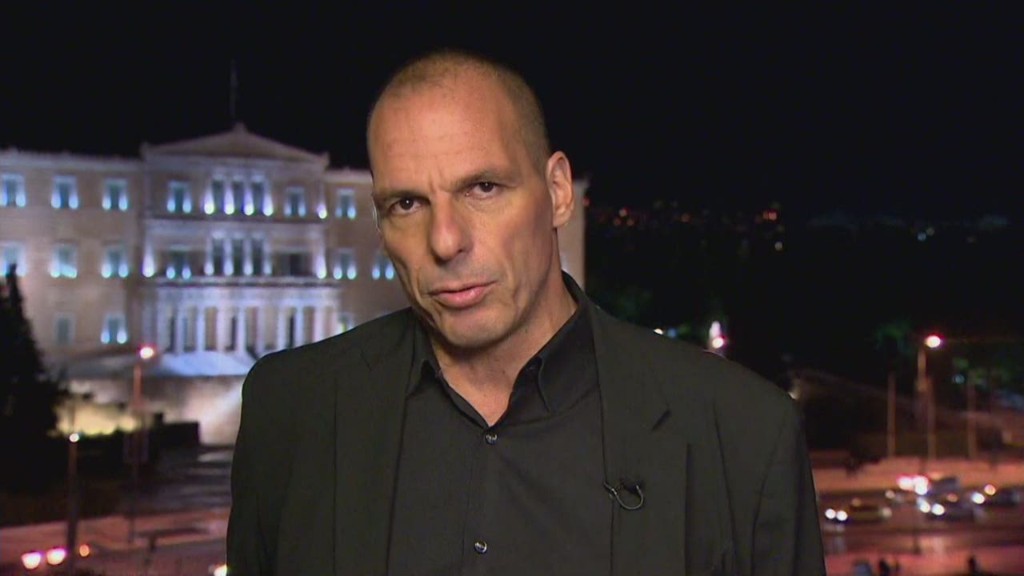

Syriza and its right-wing coalition partner have been supportive of Putin and deeper cooperation is likely, said Dimitris Papadimitriou, professor of politics at the University of Manchester.

The two countries have established trade ties. Almost 13% of Greek imports came from Russia in 2013, according to the IMF. Greece's share of Russian imports is much less significant. Still, the countries have agreed to make 2016 the "Year of Greece" in Russia, and the "Year of Russia" in Greece.

Against this backdrop, Greece could break ranks with its European partners over how to respond to a recent escalation of violence in Ukraine.

EU leaders said earlier this week they had evidence of growing support by Russia for separatists in eastern Ukraine. The Greek government was angry that it had not been consulted over the statement.

"Greece's disagreement was that Greece had not been asked, and that its consensus was taken for granted," a government spokesperson told CNN.

"Greece has to have an equal say in all EU decisions," the spokesperson said.

Foreign Minister Nikos Kotzias is said to have had close links to the Greek communist party during the Cold War. He also has a record of supporting Russia -- including under Putin -- Manchester University's Papadimitriou said.

Kotzias gave his support late Thursday to an EU decision to extend -- until September -- travel bans and asset freezes imposed on a list of Russian officials. But the meeting in Brussels stopped short of broadening sanctions.

Related: Syriza won. What's next for Greece

Some experts say Greece's new guard is simply trying to assert its authority. Expressing concern about sanctions is a far cry from jumping into Moscow's arms in the hope of finding a more sympathetic creditor.

"Greece needs fresh money and a reliable backstop," wrote Berenberg's Holger Schmieding in a note. "Flirting with Russia won't help Greece secure better terms from the only realistic lenders it has."

At the same time, Greece has good reasons to want to develop the relationship, and could do so in some areas without causing big problems for Europe.

One area of potential cooperation is energy. Russia scrapped plans to build a gas pipeline through the Black Sea to Europe last year, and is currently pursuing an alternative partnership with Turkey.

"Greece should be a partner in energy planning for Russia," Papadimitriou said.

Thanos Dokos, from the Hellenic Foundation for European and Foreign Policy, said Greece could also develop trade and tourism ties with Russia.

"But if the current climate between EU and Russia continues, their options are limited," Dokos.

--CNN's Elinda Labropoulou contributed to this report.