If a foreign dignitary checks into a room at one of President Trump's hotels, the hotel's profit from that stay is supposed to go to the U.S. Treasury.

The pledge was a big part of Trump's plan to counter ethics concerns created by his business interests.

Figuring out the profit on a single hotel room takes some number-crunching: If a guest orders food, how do you account for the time the executive chef spent creating the menu? What about the energy bill for the lights in the lobby?

But it can be done. The point, ethics experts say, is that it doesn't solve the conflict of interest for Trump: He's still accepting money from a foreign government.

The Trump Organization hasn't put out specifics on the donation plan, which, like the rest of Trump's arrangement on conflicts of interest, was not approved by federal ethics officials.

Alan Garten, the organization's corporate counsel, told CNN on Monday that Trump Organization finance and accounting staff would figure out the calculations.

Bjorn Hanson, a professor of hospitality at New York University, said determining per-room profit isn't easy, "but it can be done to some reasonable degree of accuracy on guest rooms."

Xavier Lividini, the managing partner at the Miami consulting firm Hospitality Advance International, said cost assessments for rooms generally account for housekeeping, supplies and energy bills. Indirect costs, like administration and marketing, can be factored in, too.

Hanson said the math would be trickier for large-scale events like banquets. And there could be other adjustments, like special room assignments, complimentary breakfasts and negotiated rates.

Still, Hanson said, it would be possible to factor those in and come up with an amount that represents how much money the hotel made off a dignitary's stay and set it aside for a donation to the U.S. government.

It's not clear how journalists can verify that the Trump Organization even followed through on its plan, or how the Treasury Department can be sure the profits were figured fairly. Treasury officials did not return a request for comment.

But siphoning off profits doesn't fix the ethics problem for Trump, said Norman Eisen, a visiting fellow at the Brookings Institution who was an ethics lawyer for former President Barack Obama.

Related: Experts say Trump's plan to leave business isn't enough

Eisen cited two 1980s opinions from the Justice Department's Office of Legal Counsel that prohibit federal employees from accepting any foreign payments, not just profits.

For the plan to work, Eisen said, the Trump Organization would have to isolate all revenue from foreign governments.

Otherwise, he said, the business will run afoul of the Emoluments Clause of the Constitution, which prohibits federal office holders from accepting any "present, emolument, office or title" from a foreign state.

"The whole thing is intellectually incoherent," said Eisen, who is one of the lawyers bringing a lawsuit that claims Trump's business ties are a Constitutional violation.

Even if Trump turned over every dollar -- not just the profit -- to the U.S. Treasury, Eisen said problems would persist.

The plan would need to include any cash flowing into Trump's golf courses and rented office or condominium spaces, he said.

And Larry Noble, general counsel of the Campaign Legal Center in Washington, doubts the Trump Organization knows for certain when it is being paid by a foreign government.

"While there are reasons why a foreign government may want to be clear it is the source of payment, I'm not sure that will always be the case," he said.

Related: Who can sue Trump over emoluments?

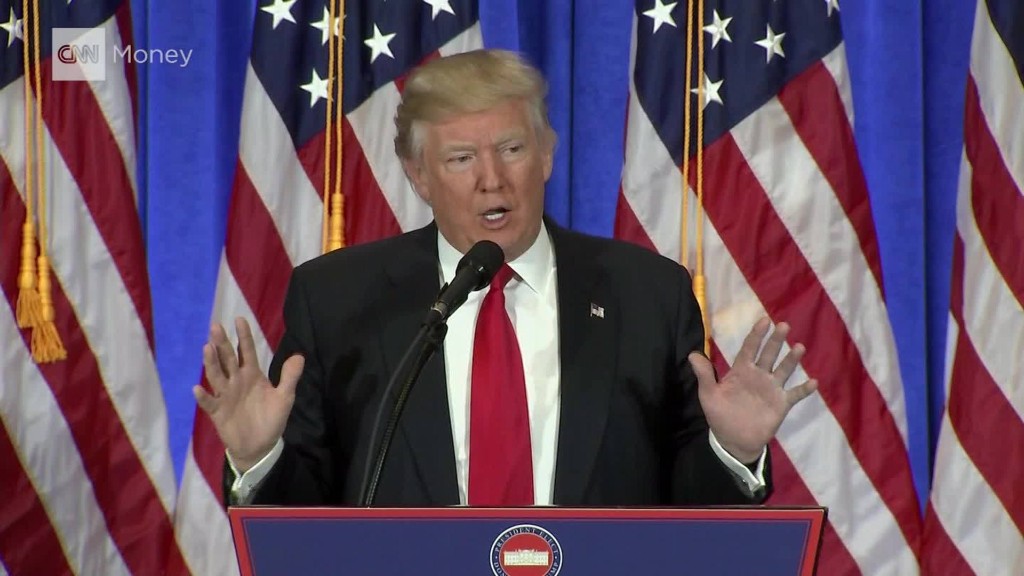

At a press conference earlier this month, Sheri Dillon, a lawyer for Trump, dismissed concerns that accepting hotel business from foreign governments would violate the Emoluments Clause.

"No one would have thought when the Constitution was written that paying your hotel bill was an emolument," she said.

Other ethics lawyers, like David Rivkin Jr., say even that defense isn't necessary.

Trump is a shareholder or partners in the companies that do business overseas, not the direct recipient of gifts or emoluments, said Rivkin, who worked in the Justice Department under Presidents Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush.

Rivkin said Trump's holdings are akin to a stockholder who owns shares in the Marriott Corporation. Would an official in that situation run afoul of the Constitution because an official of the United Arab Emirates stayed at a Marriott in Dubai?

"That absolutely does not trigger the Emoluments Clause," Rivkin said. "Think about how ridiculous that would be."

--CNN's Drew Griffin contributed to this report.