Women are constantly being told they need to be more confident.

Social media and pop culture send the same message over and over: feel more confident and you'll be more successful. Keep "confidence logs" and "brag books." Dress for success. Power pose.

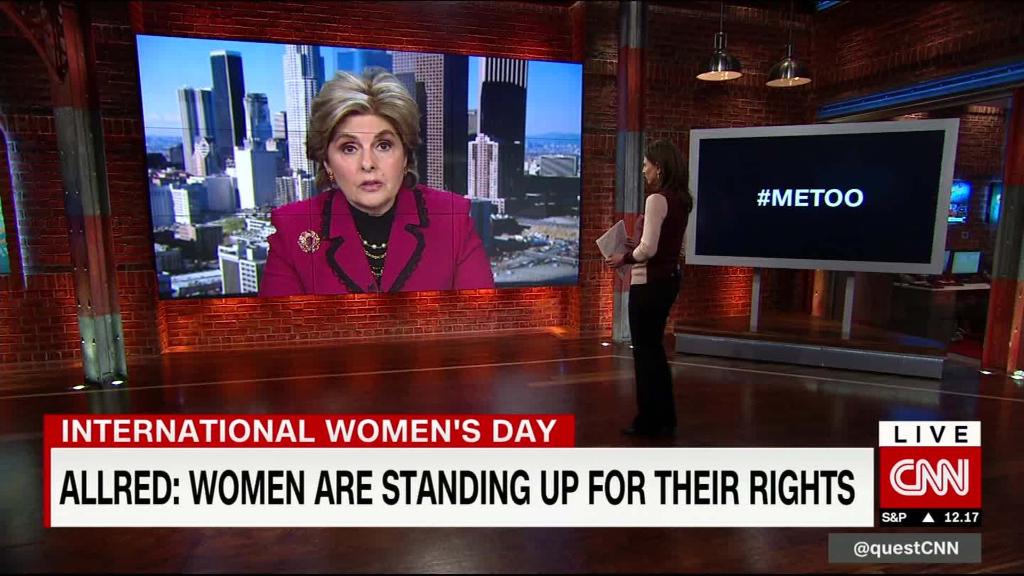

But in the last six months, the #MeToo movement has ignited a nationwide discussion about the structural barriers inhibiting women's success — pervasive cultures of harassment, limited access to male leaders, careers stalled by postponed promotions and overlooked raises. All problems a power pose can't fix.

Instagram mantras, confidence-tracking apps and self-monitoring tips from books like "Lean In" and "The Confidence Code" have created an environment that puts too much pressure on the individual, according to London School of Economics Professor Shani Orgad. She calls it "confidence culture."

"These women have internalized the blame rather than the revolution," Orgad says of "confidence culture" followers.

A 'confidence coach' taught me to be more self-confident

Self-confidence or self-deception?

The promise of these self-confidence strategies is simple: believe in yourself, or fake it until you do, and boom — success unlocked.

But self-confidence, and its companion feeling, self-efficacy, or the ability to actually achieve goals, doesn't come out of the box like that, says David Ballard, assistant executive director for organizational excellence at the American Psychological Association. Especially for women and people of color, there are systemic barriers stalling their success, regardless of their own confidence in their abilities.

How a woman's appearance can affect her career

"We know opportunities are not equal, so we can prepare individuals to address this and be successful," he says. "But if we don't simultaneously address the systemic issues, it's an uphill battle for them."

Other things outside an employee's control — like seeing role models similar to them succeed, or getting opportunities to test new skills and grapple with new challenges through "mastery experiences," as Ballard calls them — help develop self-confidence.

In a recent survey from the APA, 89% of men and 85% of women said they had the technical skills necessary to do their jobs well. But when asked if their employers had given them opportunities to learn new abilities they'd need for future career development, far fewer women than men reported seeing those opportunities.

And even when women "perform" assertiveness and other qualities we associate with self-confidence, it doesn't always work in their favor. Research shows there's often a backlash against women who act this way.

So in other words, those confidence exercises could make you feel great about your qualifications, but they won't get you the promotion.

Countering the culture

That's not to say women should balk at the occasional self-esteem boost, Ballard says. And every personality is different: some people may feel more energized by writing or repeating affirmations, while others may learn new skills when they read a confidence self-help book or ask for feedback and guidance on their executive presence.

As Ballard puts it, "The individual things are still important."

"The individual needs to develop the skills they need, they need to have the experiences that are going to lead to success, but you can't put the onus only on the individual," he says. "We have to make changes to the system as well."

But in decoding these "confidence culture" messages, confidence strategies can only do so much. Often, they're hiding the bigger picture.