NEW YORK (CNN/Money) -

Crude oil and gasoline prices, driven through the roof by worries about a possible war in Iraq, still haven't risen high enough to send the U.S. economy into recession -- but they sure aren't helping.

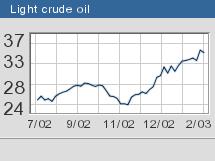

The average retail price of a gallon of gasoline jumped last week to $1.61, the highest in 19 months. Underlying that jump was a gain in the price of crude oil, which has been trading around $36 a barrel in the United States -- the highest level in two years.

| Oil and the economy

|

|

|

|

|

Crude oil prices are at least $10 higher than most industry analysts think they should be, driven up mainly by the looming possibility that the United States will go to war in Iraq, and also by fears about what impact that will have on the supply of oil from the Middle East. In addition, a two-month strike in Venezuela, the world's fifth-biggest producer, has curtailed supplies.

| Oil and you

|

|

|

|

|

"The only thing keeping prices artificially high is the potential for supply disruption," said Fadel Gheit, oil analyst at Fahnestock & Co. "Fundamentally, prices should be at $20-to-$25."

Many economists believe that every $10 gain in the price of oil cuts about a half percentage point from the growth rate of gross domestic product (GDP), the broadest measure of the nation's economy.

Though the U.S. economy is more diversified and less dependent on oil than it was in the mid-1970s, when an Arab oil embargo triggered a deep and enduring U.S. recession, higher energy costs still hurt the world's largest economy.

"Oil prices will damage the economy in the sense that they're a large 'tax' on household income, meaning spending on non-energy goods will slow down, meaning there will be less production and employment in those areas," said Kevin Logan, chief economist at Dresdner Kleinwort Wasserstein.

This is unwelcome news for a country that has been struggling to recover fully from a recession that began in March 2001.

Consumers, whose spending fuels more than two-thirds of GDP, have put up with an awful lot, including nearly two million job cuts from the recession, the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks, the collapse of Enron, WorldCom and other corporate scandals, and three years of falling stock prices.

Having to pay $1.60 a gallon to fill up the SUV probably won't be the straw that breaks a consumer's back. What's more, any consumer spending -- even if it's on boring stuff like gas and home heating oil -- does contribute to GDP somewhat.

But paying higher gas prices has at least some negative effect on consumer confidence and could put the brakes on wild spending sprees when the economy could use some wild spending sprees.

"It will take away from discretionary spending," David Resler, chief economist at Nomura Securities, told CNNfn's Halftime Report program. "It may not show up in the numbers for a few months, but it probably will cut into discretionary spending in the first part of this year."

If the uncertainty about Iraq lingers for much longer, the price of oil could continue to climb, and end up shaving a full percentage point from first-quarter GDP, according to Steven Wieting, economist at Salomon Smith Barney.

A recent survey by the National Association for Business Economics found economists, on average, expect a 2.7 percent GDP growth rate in the first quarter.

If oil prices shave GDP growth down to 2.2 percent or even 1.7 percent in the quarter, that's a much better rate than the paltry 0.7 percent growth of the fourth quarter of 2002, but still not nearly enough to inspire much job growth.

"This is a fairly big negative, correlated to other unfortunate news, like weak financial markets, which have their own impact," Wieting said. "So far it still looks like the economy is growing, but below trend."

If a war starts, all bets about oil prices are off. Oil could spike above $40 a barrel and then drop back to the mid-$20s, if the war goes quickly and well for the United States, analysts said.

But in a worst-case scenario, where terrorists sabotage oil production in Saudi Arabia, the world's biggest oil supplier, for example, prices could jump to $80 a barrel. That would be a problem, to say the least.

"Losing the Saudi oil would immediately shock the U.S. economy to the worst level in decades," said Gheit of Fahnestock & Co.

|