NEW YORK (CNN/Money) -

The once-proud U.S. dollar, battered and bruised in the past year, took another punch from new Treasury Secretary John Snow Wednesday, raising the chance that the greenback's stumble could impact U.S. and global economies -- for better or worse.

The dollar, long the currency of choice for global investors, particularly during the stock market boom of the late 1990s, has fallen about 17 percent in the past year and about 7 percent since November.

Global concern -- and outright disapproval -- of the U.S. confrontation with Iraq have fueled the dollar's decline, along with queasiness about a three-year bear market in U.S. stocks, an economy that can't seem to gather any steam, and swelling trade and budget deficits.

The unpopular currency lost even more charm when Snow commented late Tuesday that he was "not particularly concerned" about the dollar's sorry state.

"In context, those comments might have seemed fairly acceptable. But the market goes by headlines, and seeing that headline, the market sold the dollar," Jane Foley, currency strategist at Barclays Capital, told CNNfn's Market Call.

The dollar fell to a four-year low against the euro overnight, though Snow and another Treasury official stopped some of the bleeding by trying to reassure the market that they hadn't abandoned the long-standing policy of supporting a strong dollar. But many traders were skeptical.

"[Snow's comment] really does undermine the credibility of the U.S. strong dollar policy," Foley said.

The dollar fell to 117.35 yen Wednesday from 117.87 yen in the previous session, while the euro rose to $1.0959 from Tuesday's $1.0883.

Exporters' delight

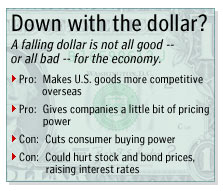

U.S. exporters would certainly love to see a falling dollar, since it makes their goods more competitive overseas. That'd be especially good news for the manufacturing sector, which has struggled since late 2000, leading to about 2 million job cuts.

And when dollars buy less, that means inflation is rising, which could ease some of the recent fears about the economy falling into a Japan-like spiral of deflation, an unstoppable drop in prices that cripples corporate profits.

"You could always think of a weak dollar as having the same impact as low interest rates," said Brown Brothers Harriman currency economist Lara Rhame. "It has a stimulative impact on the economy and puts upward pressure on inflation. That's a net gain for the U.S. economy."

But that's also a net loss for other economies, such as Germany and Japan, which have been struggling. A slump in economic activity in those countries could sap some demand for U.S. goods.

| Related stories

|

|

|

|

|

And there's another sticky problem for U.S. exporters: China pegs its currency to the dollar. In other words, a falling dollar is absolutely no help to U.S. exporters in China, one of the world's biggest economies and the nation that accounts for the biggest chunk of America's whopping trade deficit.

If consumers are paying higher prices for imported goods at a time when they're already paying through the nose for gasoline, that could put a damper on consumer confidence and spending.

"It reduces the standard of living for Americans because the cost of imports is going up," said UBS Warburg senior global economist Paul Donovan. "Americans have to work harder to buy a tank of gas [and other imported goods], so real household income is in decline."

No boon for stocks

What's more, a falling dollar could discourage foreign investors in U.S. financial markets, since the returns from their investments are coming in ever-less-useful dollars. That cuts the prices of stocks and bonds. In order to entice bond investors back to the market, yields have to go up, putting upward pressure on interest rates.

"Foreigners own 11 percent of U.S. stocks -- that's not huge, but at the margin it makes a big difference," said BMO Nesbitt Burns chief economist Sherry Cooper. "And right now there's massive foreign buying of bonds because they're a safe haven amid geopolitical uncertainty -- that could change as well."

Some economists still blame former Treasury Secretary James A. Baker III and Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan for causing the stock market crash of 1987 by cutting the dollar off at the knees, saying there was no "floor" for the greenback and that the government wouldn't stop its fall.

"In 1987 we had a sharp increase in long-term interest rates and a stock market crash when there was a run on the dollar," said Northern Trust economist Paul Kasriel. "While a lot of people think a weaker dollar is a good thing, it essentially makes us poorer and turns out not to be a good thing."

Right now, however, many economists think the greenback's recent decline is just a natural reaction to the dollar's being overvalued in the late-1990s market boom. They think a complete dollar collapse is unlikely -- it would be a pretty radical move for investors to pull all their money out of the United States, which has the world's biggest economy and some of its most liquid markets.

Such a dollar collapse, these economists think, would be necessary to do major damage to the economy and financial markets.

"Has [the falling dollar caused] an outflow of capital? Someone's buying Treasurys, and the stock market's pretty much flat, so they're not bailing out of equities," said John Davidson, president and CEO of PartnerRE Asset Management. "I don't see any evidence of it yet."

|