NEW YORK (CNN/Money) -

U.S. employers dug deep in their pockets to pay workers in the first quarter, which is good news for people whose wages have been stagnant in recent years.

But some economists worry that the trend could cause penny-pinching businesses to tighten up in the long run, keeping a lid on wage growth and stretching out the economy's run of sluggish growth.

The Employment Cost Index, a measure of how much companies shell out in wages and benefits, posted its biggest gain in nearly 13 years in the first quarter, the Labor Department reported Tuesday.

Most of the gain came from employer contributions to health-care and defined-benefit retirement plans. Wages and salaries, which can be spent right away, rose 1 percent in the quarter -- still better than nothing.

Some economists say businesses are still cutting costs and laying off workers in a bid to boost profitability and pay off debt after the boom of the late 1990s. Those businesses will find little in the news to encourage them to hire more workers or pay their current employees more -- either directly or through enhanced benefits.

"Rising benefit costs are cutting into already lean corporate profits," said Oscar Gonzalez, economist at John Hancock Financial Services Inc. in Boston. "This may cause businesses to further delay additional hiring, which is critical to boosting the sluggish economy."

Businesses might also try to get employees to pay for some of these benefits themselves, draining disposable income that consumers could otherwise spend on appliances, computers, home furnishings and services. Consumer spending fuels more than two-thirds of the nation's economy.

"With corporate profitability still under significant pressure, companies will be unwilling to meet the full cost of increases in pension plan or health-care costs," said Bijal Shah, chief global strategist at SG Cowen in London. "They'll expect employees to participate, meaning employees may have even less wage growth in the future."

Weak labor market sinks wage growth

U.S. payrolls are 2.6 million jobs lighter than they were in March 2001, when a recession started. Though the recession probably ended late that year, the labor market has remained weak. After a brief hiring spurt in 2002, the layoffs started again in the months leading up to the U.S.-led war with Iraq.

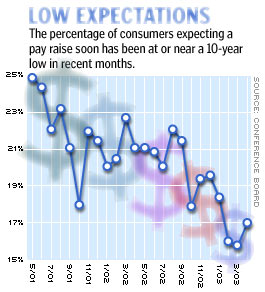

Labor-market weakness restrains wage growth -- after all, it's hard to demand a raise when there are some 8.4 million people looking for work, many of whom probably wouldn't mind taking your job, no matter how stagnant your salary might be.

Back in the good old days of the Internet boom, wages grew like gangbusters -- 7.8 percent in 1998, 6.6 percent in 1999 and a whopping 8.8 percent in 2000, according to the Commerce Department's separate measure.

The popping of the stock-market bubble and the subsequent recession brought an end to all that. Wages and salaries, as measured by the Commerce Department, grew 2.4 percent in 2001 and an even more dismal 1.1 percent in 2002.

Encouragingly, wages grew 2.97 percent between the first quarter of 2002 and the first quarter of 2003 -- almost keeping up with the 3 percent gain in the consumer price index (CPI), the Labor Department's key inflation measure, between March 2002 and March 2003.

Economists who like to strip food and energy prices from CPI noted that all other prices grew just 1.7 percent, making wage growth look even more impressive. Of course, it's awfully difficult to live without food and energy -- the prices might be annoyingly volatile, but you still have to pay them.

Most economists hope that the end of the Iraq war will lift a fog of uncertainty that's kept businesses from investing, and that all the labor-market pain of recent months has lifted productivity and profits enough to set the stage for future investment and hiring.

"Freeing up less productive resources by accomplishing more with less is the entire basis for rising living standards," said Salomon Smith Barney economist Steven Wieting. "It shouldn't come as a surprise that stronger periods of economic growth have generally begun during periods of high unemployment, not low unemployment."

Consumer confidence has clearly bounced back after the war, and retail sales are showing signs of improvement, despite last week's normal post-Easter decline -- more signs businesses could soon be convinced to crank up production.

"In the whole post-war rebound story, the first part has come through -- we've clearly seen a bounce in consumer confidence," said UBS Warburg economist Jim O'Sullivan. "The next key step is business activity measures improving, including employment indicators. Hopefully we will see weekly jobless claims coming down soon -- in the next three-to-four weeks."

Anybody got a match?

With corporate profits clearly improving in the first quarter -- companies in the Standard & Poors 500 index have so far reported year-over-year earnings per share growth of 11.7 percent -- all the wood would seem to be in place for the big corporate-spending bonfire that's needed to warm up the economy.

But one thing still seems to be missing -- the spark to get that fire going.

"Companies have the wherewithal to pick up the pace of hiring and capital investment again, but I'm not sure they have the desire, for a variety of reasons -- including their outlook on future demand," said Joshua Feinman, chief economist at Deutsche Bank Asset Management.

The economy seems stuck in a Catch-22 -- in poll after poll, corporate CEOs have expressed pessimism about future demand, and economists worry they won't start spending again until they see demand picking up. But demand might not pick up until businesses start spending again.

When businesses have to shell out a bunch of money for fixed costs such as health insurance and pension plans, some economists say the balance will be tilted in favor of continuing caution.

"The balance will eventually change, but these numbers suggest the caution businesses have been showing is warranted," said Ken Goldstein, economist at the Conference Board, the private research group that produces monthly reports on consumer confidence. "They also say we might be waiting until early 2004 before we see much stronger business investment."

|