NEW YORK (CNN/Money) - In the market's mind, Alan Greenspan is busy putting a fine edge on his machete, daubing camouflage paint on his face, catching up on his Sun Tzu.

The fight to resurrect the economy has intensified and increasingly it looks like the Federal Reserve may resort to guerilla tactics.

The signal? The Federal Open Market Committee's policy-setting meeting Tuesday. Although the FOMC, as expected, left the fed funds target rate on hold, the statement it put out following its meeting came as something of a shock.

| Fed Watch

|

|

|

|

|

In it, the Fed said "the probability of an unwelcome substantial fall in inflation, though minor, exceeds that of a pickup in inflation from its already low level."

Most observers took "a substantial fall in inflation" to mean deflation, the phenomenon of lower prices that can sap an economy. But it was not the Fed's apparent worry over deflation that got investors stirred up -- whatever the potential for deflation is, it was there before Tuesday.

Rather it was the FOMC's suggestion that there is some appropriate level for inflation -- a big shift for a Fed that has long decried the idea of establishing an "inflation target." Recently a number of observers have said it would make sense for the Fed to adopt an explicit target in the current environment because, they argue, it would take away expectations that the Fed will raise rates immediately when the economy improves (inflation takes time to build up steam). That, in turn, would help foster confidence among businesses and consumers, helping spur spending.

Serpentine, Alan, serpentine!

Not everybody at the Fed has been against inflation targeting. As a Princeton economics professor, Ben Bernanke, who became a Fed governor in August, caused something of a stir in 1999 when he co-authored a paper -- "Monetary Policy and Asset Price Volatility" -- that suggested inflation targeting was the right thing to do. The FOMC statement made investors think the Fed is coming around to Bernanke's way of thinking.

This notion, in turn, led market participants to some of Bernanke's other ideas -- specifically the ones he put forth in a November speech titled "Deflation: Making Sure 'It' Doesn't Happen Here." In it, Bernanke suggested a number of tactics that the Fed might use once it runs out of room to cut rates.

Chief among them was the idea that the Fed would adopt "explicit ceilings" on Treasury yields, and would keep yields from rising above them by "committing to make unlimited purchases" of Treasurys maturing within the next two years. "The thought is that the downturn in rates would lower borrowing costs and fuel spending," said Morgan Stanley economist Bill Sullivan.

Mortgage rates, for instance, are tied closely to Treasury yields. Bring Treasury yields down, and more households can refinance -- putting more money into their pockets. Corporate bonds, too, are tied to Treasurys. Lower companies' cost to raise money in the bond market, and they can borrow -- and thus spend -- more.

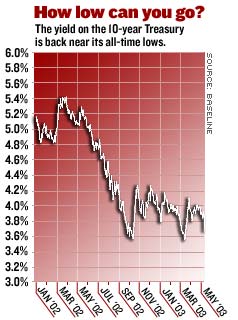

With investors thinking that the Fed might be coming into the market, Treasury bonds have rallied sharply since the FOMC meeting, pushing the yield on the 10-year note to 3.65 percent from 3.89 percent.

The only time the 10-year yield has ever been lower was briefly in October, when investors worried that financial markets were on the verge of seizing up, and again early March, when nervousness over the war with Iraq was at its most intense.

In truth, it seems unlikely that the Fed would step in and buy at this juncture, said Kirlin Securities fixed income and economic strategist Brian Reynolds -- it still has room to move on rates, after all, and financial conditions in the stock and corporate bond markets have gotten easier.

Still, Reynolds says he's getting calls and e-mails all the time from investors spouting conspiracy theories that the Fed is already buying big in the bond market.

It looks like the Fed may be getting its wish without having to lift a finger. Investors are dashing into the Treasury market, keeping rates nice and low, but the dash hasn't been associated with the sort of fear that can debilitate the stock and corporate bond markets. Rather, stocks have held up nicely since the Fed meeting, and corporate bonds have moved higher. It's the best of all possible worlds -- as good a market environment for fostering growth as one can imagine.

"The Fed set the market up for speculation," Reynolds said. "It's jawboning people into buying Treasurys."

|