NEW YORK (CNN/Money) -

The most valuable man on any baseball team's payroll is a failed journeyman who never lived up to scouts' assessment of his talents.

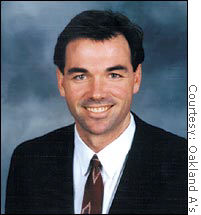

Billy Beane was once a first-round draft pick who played less than a season's worth of games spread across six years and four different teams.

Today, as general manager of the low-revenue, low-payroll Oakland Athletics, he is finding a way to win on a shoestring, picking players for their skills and track records, rather than any display of athletic ability or potential like Beane once showed.

Beane's method has worked. Despite one of the lowest payrolls in the majors, the A's have won more games since the start of the 2000 season than all but one other team, edging out big time franchises such as the Yankees and Braves, and blowing away many free-spending teams.

|

|

| Billy Beane's ability to exploit inefficiencies in the market for ballplayers has made the low-budget A's into winners. |

The A's roster and minor league system are full of once overlooked talent like All Star pitcher Tim Hudson, who as a college player was passed over by other teams, which generally used early-round picks on the high school pitching prospects the A's generally avoid. The A's took him with a sixth-round pick in the draft.

Beane's radical way of building a team depends upon numbers-driven analysis of how best to produce victories and emphasizes such unglamorous statistics as walks over flashier measures such as stolen bases or batting average. The team then fixes each player's value base on his contribution according to that analysis, rather than scouts' or other baseball experts' assessment of his abilities.

Beane has used that analysis to grab many valuable players from other teams, peddling overvalued players of his own in return. His role is not unlike a Wall Street trader exploiting market inefficiencies. And Beane's method is well documented by an observer of that world.

Michael Lewis, a former Salomon Brothers trader whose book "Liar's Poker" got behind the closed doors of Wall Street, was given near-total access to Beane and the A's organization last season to write a book due next month, "Moneyball."

| SportsBiz

|

|

| Click here for SI.com sports coverage

|

|

|

|

Given the A's success the last few years, it would seem that the team allowed what should be some pretty well-protected secrets out of the bag. The team's analysis and puncturing of myths are spelled out clearly enough in the book that you would assume that any team hoping to match the A's success would follow the game plan. The inefficiencies Beane depends on exploiting should quickly vanish.

But Lewis and a team spokesman told me this week Beane and the A's aren't worried about that threat.

"Everyone in baseball knows everybody else's business. People know we do business a little different," said A's spokesman Jim Young.

Can the A's keep their edge?

Lewis isn't so sure they should be so sanguine.

"They believe that for the guys who didn't get it, no book is going to make any difference," said Lewis. "Billy says, 'By the time there are no inefficiencies to exploit, I'll be retired.' But if I was an owner of a baseball team and someone finally puts a fine point on inefficiency in baseball and a way of doing things that doesn't involve spending Yankees-size money, I might pay attention."

Indeed, the Boston Red Sox and Toronto Blue Jays now have general managers, one a former Beane assistant, who emphasize Beane-like analysis. But other experts say that even if more teams start to get it, there will be enough teams evaluating talent and value the old fashioned way for the A's to keep winning.

| Related stories

|

|

|

|

|

"If Boston and Oakland start competing to draft players no one else wants, each will get half," said Doug Pappas, a New York attorney and expert on baseball economics. "As long as the A's keep churning out talent from the draft and the farm system, they'll be fine."

But I think the clock probably is ticking on the A's advantage.

The last radical change in player evaluation started in the late 1940s, when the Dodgers became the first team to sign black players. Most other teams overcame that entrenched prejudice within a decade.

There's a clear prejudice against many players Beane likes -- players who are fat or slow or who can't throw very hard. But books like "Moneyball" should convince enough teams to re-examine and abandon those prejudices, especially when they understand just how much money they can save doing so.

Paying for potential

The big business of sports news this week shows that teams aren't the only ones overpaying for sports potential. Nike (NKE: Research, Estimates) agreed to pay $90 million to high school star LeBron James, the likely first pick in next month's National Basketball Association draft. As I wrote in an earlier column, Nike hopes that he'll be the next Michael Jordan of endorsements.

Since all the established NBA stars have proven that they can't be the next Jordan when it comes to selling shoes, the shoe companies were willing to bid top dollar for the untested James in hopes that he might be able to be the elusive "next Jordan." No matter how he performs on the court, it'll be tough for him to justify that kind of endorsement money, though.

|