NEW YORK (CNN/Money) - In Philadelphia, home of Independence Hall and the Liberty Bell, residents and politicians are celebrating their latest symbol of freedom -- a hoagie in a clear plastic bag.

This summer the hottest topic in the City of Brotherly Love and rabid fans was a proposed ban on bringing food into the new football stadium -- Lincoln Financial Field -- which is opening with exhibition games this month.

Fans decried it as an attempt to pump up concession revenue at the new publicly-financed park, and politicians prepared to offer "Joe Six Pack 'Own Food' Rights" legislation. Give me cheesesteaks, or give me death!

|

|

| Philadelphia Eagles fans can keep bringing their own cheesesteaks to games, but the team won't take much of a hit because of it. |

Team officials argued that concession revenue wasn't the issue, that the ban was purely for security reasons, to allow quicker access to the park without time-consuming searches. Trying to convince fans of that was like trying to convince them to cheer local athletes who fail despite trying their best.

So a week ago the team gave in to popular opinion and announced the food would be allowed in.

But while I hate to take the point of view of ownership in a battle over money, this is one time that the team executives were telling the truth, more or less.

|

|

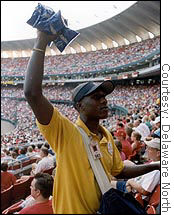

| A few pennies of peanuts for a few dollars still doesn't mean a windfall for sports teams. |

Despite the prices that can force fans to refinance their mortgage before buying a meal for their family each game, the extra concession revenue that a food ban would generate is negligible for the team. Unlike movie theaters, where the popcorn sales actually keep the doors open, the real money for sports teams is at the ticket window and broadcast booth, not the concession stand.

First of all, most teams get only a percentage of concession sales. Very few operate the stands themselves. Estimates on spending per fan range from $8-to-$10 at basketball and hockey, $10-to-$12 at baseball, and $12-to-$15 per fan at football games. And the teams only hang onto between 35 and 45 percent of that spending under concession contracts.

| SportsBiz

|

|

| Click here for SI.com sports coverage

|

|

|

|

The one hard (or semi-hard) set of data is the 2001 baseball season financial data, released to Congress when it was holding hearings on the sport's finances. That showed that the "other revenue" category, which did not include ticket sales or broadcast rights but did include concessions, parking, stadium advertising and the like, averaged $11.40 for every fan who attended a game. And remember, that included all manner of non-ticket, non-broadcast money, such as revenue from the signs that mar the stadium and commercials that assault fans from the jumbotrons.

The stadium concession operator at Lincoln Financial Field as well as the consultant who advised the Eagles on its concessions deal both told me that the first time they heard about the food ban was when the controversy hit local papers.

| Related columns

|

|

|

|

|

"I'm from Philadelphia originally, and my family members called me and said, 'Your clients are causing all types of problems,'" said Chris Bigelow, a leading food services consultant who advises teams and stadium owners how to get the best deal from concession operators. "Certainly if you allow alcohol in, as a lot of Nascar tracks used to do, it would be a huge difference in revenue. But that person bringing their own food is probably not buying from concession stand anyway. It's a negligible difference, and not something that would ever be specified in a concession contract."

Jerry Jacobs, executive vice president of Delaware North Corp., which runs concessions at the field, said he's not at all concerned about the flow of hoagies and cheesesteaks into the new stadium.

"It is minimal. It gets lost in rounding. It's not something that we really quantify," Jacobs said. "Tailgating is where the real impact lies. But football fans can't carry all the food they eat."

Even some of the fans who were upset about the ban admitted it was the principle of the thing, and the team's approach to the dispute, that upset them more than any plan they personally had to bring their own. Philadelphia lawyer Chuck Goodwin told me he's pleased the ban was lifted, even though he always planned to buy food at the stadium when attending the game.

"Lugging food around to a preseason game when it's hot there, that's just asking for ptomaine poisoning," he said.

|