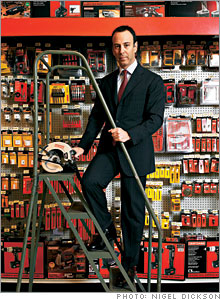

How Eddie Lampert picks his stocks

In its 18-year history, his hedge fund has averaged nearly 30 percent returns. What makes Lampert so good?

NEW YORK (FORTUNE Magazine) - Like Warren Buffett, Eddie Lampert calls himself a "value investor," meaning he buys into companies whose assets he calculates are worth more than the current trading price. "The idea is that I'm going to pay this price and great things may happen, but they don't have to happen for me to do okay," he says.

He typically doesn't short stocks, trade currencies or derivatives, take on substantial leverage, or do any of the fancy stuff that most hedge funds do. His firm, ESL Investments, employs 20 people, whereas another hedge fund its size (there are just a few) would have hundreds and a busy trading floor. "We try to stay very focused," Lampert says. He takes large positions in major companies and typically holds them for a long time. See FORTUNE's full profile of Eddie Lampert: "The best investor of his generation." He has owned AutoZone and AutoNation, his two biggest investments besides Sears Holdings (Research), since 1997 and 2000, respectively. ESL now owns about 29 percent of each company. Lampert's stock picking is a "form of immersion," he says. Before he put a penny into AutoZone, he visited dozens of the auto-parts retailer's outlets and had one of ESL's analysts spend six months calling on hundreds of stores, posing as a demanding customer. "It's probably overkill," Lampert says, but he can't resist. "Eddie doesn't do things that 99 percent of the hedge fund world does," says Tom Tisch, an ESL limited partner since 1992. To avoid pressure to sell his holdings prematurely, Lampert requires ESL's investors to commit their money for five years -- rare in the hedge fund world, where the standard lockup is one year. Lampert also believes that secrecy is a key advantage for an investor. Because ESL today owns such large stakes in companies, those holdings must be publicly disclosed. But Lampert still refuses to talk about the specifics of his portfolio, even with his own investors. In the past Lampert has had occasional conflicts with his limited partners over this policy. Media mogul David Geffen, who has invested with Lampert since 1992, recalls insisting to him at one point, "I want to know where the hell my money is." Lampert refused to tell him. "The rules are the rules, and they're the same for everybody," says Geffen. "Eddie is very strict. It's one of the things I admire about Eddie. But I don't like it about him." Of course, much has changed since Lampert made the biggest bet of his career: his $12 billion acquisition of Sears. He used to wield his influence quietly at companies -- by shaking up management and imposing financial discipline from his seat inside the boardroom. Now, by taking an active role in running Sears Holdings, he is veering from his old self and from Buffett, who takes pains to avoid meddling in management. Buffett also tends to buy well-run market leaders -- such as Wal-Mart (whose stock he bought last year) rather than its downtrodden victims like Kmart and Sears. "Warren Buffett says, 'I'd rather jump over a one-foot hurdle than a six-foot hurdle,' " says Lampert. "We'd rather jump over a one-foot hurdle too. But it's difficult to find the opportunity. So I'm willing to engage more in underperforming companies."

See FORTUNE's full profile of Eddie Lampert: "The best investor of his generation." |

| |||||||||||||||