|

A to-do list for Pfizer's Kindler The new CEO faces a bunch of chores, including putting some life back into the stock. NEW YORK (CNNMoney.com) -- The biggest drug company in the world has a new man at the helm, and analysts are hoping Jeffrey Kindler won't make the same mistakes as his outgoing predecessor, Henry McKinnell. While Pfizer (down $0.40 to $25.59, Charts) vice chairmen David Shedlarz and Karen Katen seemed like obvious picks for the top job, the board of directors passed them by.

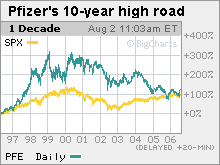

Instead, the board picked the company's top lawyer: An unexpected choice but a relevant one at a time when Big Pharma spends much of its time in court fighting patent challenges and allegations of deadly drugs. When Kindler accepted the job Friday, he vowed to "transform every aspect of how we do business, focusing on actions that create and sustain value for our shareholders." He also said, in a letter to colleagues, "We need to look at everything we do with fresh eyes to make sure we're adapting to our changing environment as rapidly as that environment is changing." But it's unknown whether Kindler has what it takes to reel in profitable new drugs, through acquisitions, licensing or research and development, as he tries to restore the company to growth. What is known about Kindler? Not as much as analysts would like. Several said they're hoping that he won't keep his cards too close to his chest, like "Hank" McKinnell. "McKinnell was not as accessible as some of the other pharma CEOs," said Les Funtleyder, analyst for Miller Tabak. "If [Kindler's] just a little bit more accessible to the Street, it will probably help the stock." Pfizer's fresh face Kindler, who only joined Pfizer in 2002, is a youthful 51-year-old former executive at McDonald's (Charts), where he spearheaded the acquisition of Boston Market and became the subsidiary's CEO. That experience might be helpful at Pfizer, which recently sold off its consumer products division for $16.6 billion. The company said it will use the money to purchase new products, though Pfizer spokesman Paul Fitzhenry declined to comment on Kindler's specific plans for the company. "I don't buy that [Kindler] can do deals better than Shedlarz or Katen," said Funtleyder, referring to the execs who got passed up for CEO. "Pharma deals are different than fast food deals, because pills aren't French fries." But maybe Pfizer needs a breath of fresh air. The drug giant is losing blockbusters as their patents expire, evaporating billions of dollars in revenue without having enough meat in its pipeline to fill the vacuum. Most recently, the patent ran out on the antidepressant Zoloft, which used to bring in $3.3 billion in annual revenue, most of that probably lost to lower-cost generic competitors. To make matters worse, future sales growth for Lipitor, the cholesterol drug that is the world's biggest selling medicine, raking in $12.2 billion last year, is uncertain. Incoming products Exubera, the first form of inhalable insulin for diabetics, and Chantix, a smoking cessation drug, might not be enough to help restore growth, industry analysts said. These problems are synonymous with Big Pharma and well known to investors, but solutions don't come so easy. Pfizer's $4 billion dollar cost-cutting effort helps patch up some of the damage, but it won't create growth. The billions of fresh revenue from selling off the consumer division could help Pfizer buy smaller companies with promising pipelines, but that's a failed gamble if the products don't pan out. Investors, meanwhile, are pining for the glory days of the 1990s, when Pfizer stock soared. Since early 2000, the stock's dropped about 45 percent. Sabrina Carollo, research analyst for Ariel Capital Management, a holder of 37,000 Pfizer shares, said that Kindler's four years with the company pales compared to McKinnell's 35, making him practically an outsider, and a welcome breath of fresh air. "It's a good time to bring in someone from the outside to look deeper into the company to get a new set of eyes," said Carollo. In this sense, Kindler might be able to bring about a change in corporate culture. "What [Kindler] brings to the table is a non-Pfizer perspective, and you can tell by Pfizer's perspective that the strategy needs to change," said Funtleyder, who hopes that Kindler can prompt the scientists in R&D to take more risks in testing drugs, without fear of termination if they don't work out. Showing Hank the door McKinnell was originally supposed to retire in February 2008 after more than 35 years with the company but he's leaving a year early. McKinnell, 63, has been unpopular with shareholders and analysts who said he wasn't forthcoming enough about his plans for New York-based Pfizer. When a company is hemorrhaging value, shareholders want answers, and since McKinnell took the helm in May 2001, the stock has tumbled about 40 percent versus a drop of about 25 percent for the U.S. drug sector and a 2 percent rise for the S&P 500 from the index's low that month. "I think people will tolerate certain kinds of behavior [when a company is successful,] but when your performance is less than competitive, it becomes a real liability," said Barbara Ryan, analyst for Deutsche Bank North America. She added that McKinnell "turned a deaf ear to his constituents" on Wall Street. And did McKinnell really deserve that $83 million retirement package? He became a "lightning rod for the issues of executive compensation and that contributed to his early retirement," said Ryan, adding that while Kindler is more "personable" than McKinnell, she couldn't say whether he'll bridge the gap between management and shareholders. "What he does at Pfizer remains to be seen," said Ryan. Ryan and Funtleyder do not own shares of Pfizer stock, but Deutsche Bank does. ______________________________ |

|