|

The big difficult The whole country needs a recovered New Orleans. But that doesn't mean it will happen.

NEW YORK (Fortune) -- As the first anniversary of Katrina approaches, New Orleans has made progress. Gas and electricity have been almost fully restored, though outages remain frequent; as of July, most residents had full postal service. The Army Corps of Engineers has almost finished removing the 300,000 refrigerators in people's yards and has begun work on the 250,000 wrecked cars still on the streets. In mid-June the Corps completed its first-pass rehabilitation of the city's levee and pump system.

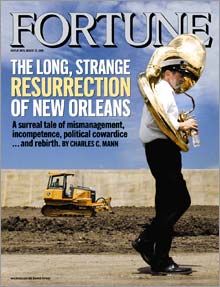

(This is an excerpt from a story in the August 21 issue of Fortune, "The Long Strange Resurrection of New Orleans.") After a long, divisive campaign, the city settled its leadership question by unenthusiastically reelecting Mayor Ray Nagin in late May. Three weeks later, congressional negotiators assembled the last elements of a package to help householders rebuild; it is expected to be fully operational by the end of August. More important, displaced people have been moving back. According to the mayor's office, the city's population is already "north of 250,000." (Most other estimates are around 200,000; the city's prestorm population was about 455,000.) Failing to rebuild a viable city would have consequences far beyond Louisiana. New Orleans' two ports are, by tonnage, the nation's biggest. They need to be - the region handles a third of the nation's seafood and more than a quarter of its oil and natural gas. Some 4,000 oil and natural-gas platforms, linked by 33,000 miles of pipeline, spread out along the Louisiana coast. Among the facilities are the four largest refineries in the Western Hemisphere. Southern Louisiana is easily as important to the nation's energy supply as the Persian Gulf. Despite the nation's need for a recovered New Orleans, the situation remains parlous. Hurricane season is racing to its peak, and the city's infrastructure is so weak another Katrina would finish it off. But even if no hurricanes strike the coast, the city and region must still navigate through three intertwined dilemmas. The first comprises the obvious problems of deciding what areas will be rebuilt and ensuring that the city is protected by a new, stronger levee-and-pump network. Finishing that system will take many years, and until then, people and businesses will be reluctant to invest themselves in the area, slowing recovery. Even as the city reconfigures itself, a second, still bigger reconstruction project must occur in the great wetlands to its south. New Orleans' best defense against hurricanes is not its levees but this vast Delta swamp, which acts as a buffer against storm surges from the Gulf of Mexico. Alas, the coastal wetlands, by far the nation's largest, are disappearing, literally dissolving away. Halting and even partially reversing the land loss is possible. But it will require the biggest, costliest restoration effort ever tried, all at a time when war, tax cuts and Medicare have depleted the federal treasury. Those two projects - reconfiguring New Orleans and rehabilitating its ecosystem - are daunting enough, and working through them will require a stupendous force of political will, especially in Washington. Here is the third dilemma: That desperately needed political will is nowhere to be seen. The scale of this rebuilding effort is a reminder of the need for effective government. Yet New Orleans' best chance for recovery may lie in its reawakened sense of community, born of shared disaster - because government, it is now clear, will not act unless pushed hard. _______________________

|

|