|

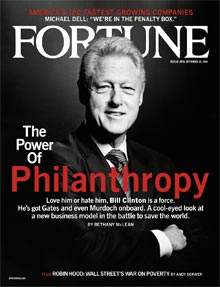

Making a difference, the Clinton way How does a philanthropy without money do so much? Star power and a unique combination of optimism and pragmatism.

NEW YORK (Fortune) -- The Clinton Foundation is not a foundation at all in the traditional sense, because it has no money of its own. What it does have, of course, is Bill Clinton and all he brings with him: what Dr. Richard Feachem, executive director of the Global Fund, calls his "personal bully pulpit"; what Bob Carson, outgoing chairman of the American Heart Association, calls his "mind-boggling convening power"; what Doug Band, who began as Clinton's personal aide in the White House and now carries the title of counselor, calls his "ability to motivate people and move mountains."

(This is an excerpt from a story that ran in the Sept. 18 issue of Fortune. Read the complete story to find out more about how the Clinton Foundation takes on problems like AIDS in Africa.) The people he motivates are an odd but potent mix of longtime allies and FOBs, doctors and activists, and executives ranging from the unknown and enormously dedicated (like Clinton Foundation Rwanda director Beth Collins) to the high-profile and frankly improbable (longtime nemesis Rupert Murdoch, who is bankrolling a global-warming initiative). "We take a lot of cues from the business world," says Clinton, who these days can sound more like a CEO than a politician. "We have very entrepreneurial people and a very entrepreneurial process. We identify a problem, we analyze it, and we move." Much of his staff comes from business, and he says using business practices "allows us to do a lot with relatively small resources." Overseas assignments don't come with a car and driver or first-class airfare. "Your job satisfaction is not my main concern," policy chairman Ira Magaziner, an FOB for almost 40 years, likes to tell the staff. "You can sit in coach for ten hours." The foundation's 2006 budget is just $30 million; next year it will roughly double. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, by contrast, has a $30 billion endowment. "Yeah, I'd like to have his money," says Clinton of Gates. "But I think our way adds value. It's kind of a pain to always ask for financing, but perhaps it forces you to look closely." "We have a culture of getting s**t done. It is very empowering and very unforgiving," says Anil Soni, a former McKinsey consultant who is now COO of Clinton's HIV/AIDS initiative. "Ira and Clinton will say, 'People are going to die tomorrow if we don't do this.' And it's true." The foundation doesn't have a clearly defined hierarchy or a detailed business plan. Its tentacles sprout from need, opportunity, and passion rather than design. "We don't have committees, we don't have processes," says foundation CEO Bruce Lindsey, who has been with Clinton since Arkansas. "If a decision needs to be made, we make it. If we can help, we help now, not tomorrow." The foundation operates a bit like a management consulting firm - burrowing into and improving the work of larger organizations - albeit one that is out to rescue the world from the dark threats of poverty, AIDS, climate change, and childhood obesity. "The scale and ambition were startling," says Mala Gaonkar, a hedge fund manager at Lone Pine Capital who gives money to Clinton. "I'm an analytical person.The foundation is very good at saying, 'Here are the outcomes, here are the metrics, here's how we've done.' " Since we're talking about Bill Clinton, you'll also hear criticisms. His foundation is just a way to keep the cameras and the crowds coming. He's just doing it to help his wife. He overpromises and underdelivers. He grabs credit for the work of others. He's searching for redemption. There's probably some truth to all of them. Certainly nobody soaks up the spotlight like Clinton - of course he got together with Madonna to discuss what they might do to save Malawi. And inevitably, all the showmanship can make you wonder about the substance. But to criticize is also to acknowledge that the bar is higher for Clinton than for anyone else. Instead of joining corporate boards, he's attacking many of the world's most intractable problems. He is not going for the quick hits; he's going where others haven't. And he agrees that the bar should be set high: "I believe a lot should be expected of me because I was given an astonishing life." He also says he has opportunities now that he didn't have as president. "The raw power [of the presidency] can be way oversold. There are limits to it." Unique as it is, the Clinton Foundation also stands for something larger than itself. "I am trying to do this in a way that will inspire other people," he says. "I hope the way we do things will become more the norm." Like the Gates Foundation and Robin Hood, the Clinton Foundation is part of a new turn in philanthropy, in which the lines between not-for-profits, politics, and business tend to blur. In this hardheaded philanthropic world, outcomes matter more than intentions, influence isn't measured in dollars alone, and you hear buzzwords like "scalability," "sustainability," and "measurability" all the time. As Clinton says, "It's nice to be goodhearted, but in the end that's nothing more than self-indulgence." (This is an excerpt from a story that ran in the Sept. 18 issue of Fortune. Read the complete story .) |

|