When Crocs attack, an ugly shoe taleWith a battle plan based on 'thinking bigger than you are,' the maker of the world's ugliest shoe takes the footwear business by storm.(Business 2.0 Magazine) -- By now, you've probably heard the unlikely story of Crocs - not the rugged-skinned reptiles but the equally strange-looking shoes that have become a global phenomenon. It's quite a tale: Three pals from Boulder, Colo., go sailing in the Caribbean, where a foam clog one had bought in Canada inspires them to build a business around it. Despite a lack of VC funding and the derision of foot fashionistas, the multicolored Crocs - with their Swiss-cheese perforations, cushy orthotic beds, and odor-preventing material - become a global smash.

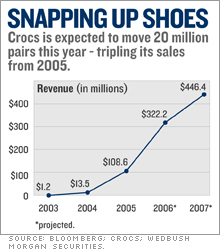

Celebrities adopt them. Young people adore them. The company goes from $1 million in revenue in 2003 to a projected $322 million this year. Crocs Inc.'s IPO in February was the richest in footwear history, and the company has a market cap of more than $1 billion. But there's more than luck to Crocs's astonishing success. Its founders - and especially the CEO they brought in two years ago, former Flextronics executive Ron Snyder - made some shrewd and instructive business moves that proved crucial. A plan to take it easy Crocs's founders - Lyndon "Duke" Hanson, Scott Seamans, and George Boedecker - almost blundered into their success. (Boedecker resigned this year, three days before being arrested for threatening to slit his brother-in-law's throat; a personal settlement was reached, and the charges were dismissed.) They leased their first warehouse in Florida "specifically so we could work when we went on sailing trips there," Hanson says. "From the get-go, we mixed business with pleasure." The shoes were first sold to sailing enthusiasts but soon gained a word-of-mouth following among doctors, gardeners, waiters, and other people who have to be on their feet all day. In fact, it was Snyder who really lit Crocs's fuse. He was kicking back after a four-year stint running Flextronics's global division, where he helped the giant contract manufacturer grow from $3 billion in annual sales to $16 billion. Then the Crocs founders, old college friends of his, asked him to do some consulting for the fledgling company. "I thought I'd work a few hours a day," Snyder says. "I thought it would be restful." Then he saw how fast sales were accelerating on mere word-of-mouth marketing and agreed to take on the CEO role. "Ron got us to start thinking big," Hanson says. "He said, 'You can be a worldwide force.'" The accidental entrepreneur: a $10 Million Crocs tale Snyder saw that Crocs were cheap enough - $30 a pair - that some customers bought multiple pairs for special occasions. "We'd get requests for red around Valentine's Day and decided to make more red," he says. "Then we decided to base our business model on this - to deliver styles and colors customers want, and deliver them right away." An industry on its heels Simple as it sounds, that turned the shoe industry's distribution model on its head. Usually retailers have to purchase their spring line of shoes, say, six months in advance and buy in bulk. With Crocs, they can reorder as few as 24 pairs and stock them on shelves in a matter of weeks. Best of all, they aren't left with unsold shoes they have to discount - so Crocs are always sold at a consistent price. "They've surprised everybody," says Jim Duffy of Thomas Weisel Partners. "Their replenishment system is unheard-of in the retail footwear space. It helped that in 2004, Snyder decided to buy Finproject NA - the Canadian manufacturer that made Crocs and owned the formula for the special resin, called Croslite, that gives the soles their unusual comfort and their odor resistance. Until then Crocs had basically been ordering and distributing Fin's product. Now it had control over manufacturing and timing. Hanson calls it "the tail buying the dog"; Snyder declares it a "eureka" moment. "We had everything required to take the company to the next level," he says. "Proprietary processes, proprietary material, intellectual property, and distribution." A one shoe company? Ask Al The next level, of course, was nothing less than taking over the world. Snyder says the lesson he learned at Flextronics was "Think bigger than you are." So he added manufacturing plants in China, Italy, Mexico, and Romania. Crocs's reach became vast: One in six people in Israel, for example, owns a pair. "Deciding to create a global infrastructure significantly added to our success," Snyder says. And how. Revenue for the first half of 2006 was up 255 percent on 2005's impressive record, largely due to the rise in international sales. At first, Crocs predicted that foreign sales would make up 10 percent of the year's total; in fact, they're currently at 30 percent. Crocs now sells shoes in more than 40 countries. All told, it expects to sell 20 million pairs this year. With celebrities from Al Pacino to Faith Hill sporting the clogs, Crocs could hardly ask for better marketing. Yet the company isn't sitting still. This winter it plans to open its own 1,600-square-foot retail store in New York City's SoHo neighborhood. It's producing special branded Crocs for companies like Googl (Charts)e, Tyco (Charts), and - yes - Flextronics (Charts), as well as sports teams like the L.A. Lakers. Snyder is spending $4 million a year to sponsor the AVP volleyball tournament for the next three years. Seventy colleges are getting Crocs for their students in school colors, with preorders of more than half a million pairs. Much of this strategy is aimed at preserving Crocs's grip on its most fickle following, the youth market. Take its recent deal with Walt Disney (Charts): Shoes with Mickey Mouse-shaped holes will be available by the holidays, with other Disney-themed Crocs to follow in 2007, timed to Disney movie releases. That, Snyder hopes, will help offset the copycat factor. (Crocs has filed patent infringement cases against 11 rivals.) Hiring All-Stars Snyder is keenly aware of the threat of a sudden shift in footwear fetishes. That's where his second acquisition, of Italian footwear designer Exo, comes in. Exo's initial Crocs designs were received well by buyers and retailers at its two most recent trade shows. "People call us a one-shoe pony," Snyder says, "but we have 23 models right now and are adding another nine next spring." Plus plenty more things to put on them, thanks to the purchase of accessory maker Jibbitz (see "Instant Company, Crocs Edition," below). Crocs may still turn out to be a footwear fad - but that's no bad thing. Remember Deckers Outdoor's brand of Ugg boots, introduced in 1995? Even after the initial mania died down, Uggs saw steady growth. Sales of the boots were $110 million in 2005 and are expected to hit $122 million this year. Not bad for a brand that fashion forgot. Some analysts say Crocs's biggest issue is that consumers can't always find the colors and styles they want. "As problems go," Duffy says, "that's a pretty darned good one to have." And Snyder has hired a good-looking team: Peter Case, the new CFO, brought management and retail know-how from Ashworth and Guess, while John McCarvel, a vice president from Flextronics, now heads operations. "We hired up everywhere, probably hiring people we couldn't afford," Snyder says. "But you want the right people on the bus early." After all, someday he's going to need that rest. How a stay-at-home mom sold Crocs a $10 million idea. For more WHAT WORKS on your mobile device, go to | CNNMoney.mobi Diane Anderson is a writer and editor based in San Francisco. |

|