Problem no. 4: Dirty airSun Ovens International is saving trees and cutting deadly pollution.SAN FRANCISCO (Business 2.0 Magazine) -- The background: Most of southern Asia is enveloped by a vast cloud of smog two miles thick - a toxic stew of industrial pollutants, carbon monoxide, and particles of soot from millions of rural cooking fires. The "Asian brown cloud" has been blamed for the deaths of 500,000 people each year in India alone. A person cooking over an open fire that's burning wood or kerosene inhales the equivalent of the smoke from two packs of cigarettes a day. Respiratory infections are the leading cause of death in children under the age of 5 and kill 1.6 million people overall each year. Three billion households worldwide depend on wood and charcoal to prepare food, and the global supply of wood is rapidly declining.

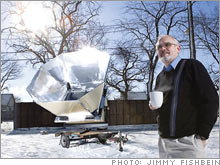

The solution: Solar power can replace wood and kerosene for cooking. Sun Ovens International, based in Elburn, Ill., sells a family-size solar oven for $259 that's used in 130 countries. A much larger solar cooker, including a trailer and a set of pots and pans, sells for $10,500 and is designed for schools, hospitals, and orphanages. It serves up to 1,200 meals a day and saves more than 150 tons of wood annually, cutting greenhouse gas emissions by an estimated 275 tons per year. The solar oven uses mirrors to redirect the sun's rays into an insulated box. The box heats up quickly, reaching 360 to 400 degrees, and can be used not only to cook food but also to purify water and dehydrate meat. "Because doing business in some of these countries is so hard, we found it best to license our technology to private-sector companies," says Sun Ovens president Paul Munsen. "We help entrepreneurs set up an assembly plant and transfer the technology for a royalty payment." Being culturally sensitive about selling a product abroad isn't just politically correct - it's good business. Sun Ovens recognized the value in having its ovens assembled in developing countries, creating jobs for residents and building a sense of ownership about the product and its success. The ovens were developed in 1985 by Tom Burns, a retired restaurateur who was concerned about deforestation. Engineers from Sandia National Laboratories helped refine the design. Several nonprofits market solar cooking devices, but there's no real competition from the private sector. The ovens have been popular in Haiti, where firewood for cooking is scarce and expensive. Later this year the U.S. and Canadian military will use them for humanitarian projects in Afghanistan, and they'll soon be available in Uganda and Nepal. The payoff: Sun Ovens has sold about 32,000 of its family-size ovens and 260 institutional units. Last year it generated $720,000 in revenue. The opportunity: Munsen estimates that there's a worldwide market for more than 300 million family-size solar ovens, which would generate at least $75 million in revenue annually, provided that funding for microloans - small credit lines extended to entrepreneurs in developing countries - could be arranged. Thanks to rising fuel costs and growing environmental concerns, the domestic market for the ovens is heating up as well, with U.S. sales growing 125 percent this year. "I see opportunity for solar ovens almost anywhere it's sunny," Munsen says. Nearly all market trends are favorable for the product. The cost of kerosene and propane used for cooking is skyrocketing in developing countries, making a solar alternative even more attractive |

Sponsors

| ||||||||||||