NEW YORK (Fortune) -- Jemima and Ricardo Sanon, 30 and 29, saw the possibility of trouble before they ever signed their mortgage documents in 2004.

The Sanons had diligently saved $5,000 in preparation to buy their first home, but the sum was just enough to cover the closing costs. So to finance the $290,000 purchase price of a Waltham, Mass home, they took one loan for $232,000 and also a piggyback loan for $58,000, both from New Century Financial, a subprime lender.

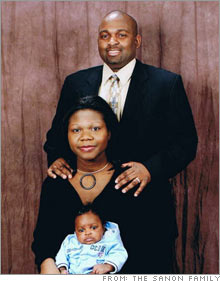

|

| The Sanon family |

The smaller of the two mortgages didn't worry them. The terms were fixed for 30 years at 10.7 percent, and the monthly payment of $538 was something they felt they could handle.

But the larger loan was fixed for just two years. After that, the rate would adjust every six months, which is typical for subprime borrowers.

"I worried about how we would make payments when they increased," said Jemima, a medical assistant. "The mortgage broker [at New Century] told us we could refinance." A spokeswoman for New Century declined to comment on the specifics of the Sanon's case citing privacy issues, but she did issue this statement: "New Century is offering special programs that are designed exclusively for current New Century borrowers who are most susceptible to payment shock at the reset of their loans."

Fast forward a couple of years, and the Sanons, like so many other subprime borrowers today, are struggling to keep their heads above water. As the housing market boomed, refinancing or selling your home was a simple solution for borrowers who had trouble making the mortgage payment. Now that the housing market has stalled, subprime borrowers are stuck with loans they really couldn't afford in the first place.

Defaults and foreclosures are rising, and the industry is roiling as lenders face the consequences after years of handing out money irresponsibly. Says Bruce Marks, CEO of Neighborhood Assistance Corporation of America, a non-profit that is trying to help the Sanons and other subprime borrowers refinance into sensible mortgages: "Lenders knew these loans were structured to fail."

For the Sanons, the initial monthly payment on the larger loan was some $1,300. Two years later, that payment jumped to over $1,800.

As a result of the sticker shock, the couple fell behind on their credit cards and student loans.

In November, Jemima had to leave her job for several months because of a difficult pregnancy, which put them even further behind on the bills. She recently returned to work. But not in time to stay current with the mortgage; in February, the Sanons paid late. Now the March payments are due, and the latest adjustment has pushed the sum on the larger loan to over $2,000.

After the first adjustment, Ricardo called Litton Loan Servicing (the company currently servicing the mortgage) to try to work something out. "They threatened us," he says. "They said, 'If you don't make your payment, we'll foreclose.'"

Says Larry Litton Jr., CEO of Litton: "Tell them to call my office. If they can show us through their financial statements that they're going to have problems affording the escalated payment, we will be more than happy to modify that loan that day because the last thing we want is that house back."

Ricardo says, No thanks. He's working with Marks' organization to try to get into a loan that makes sense.

In the meantime, he has been logging seven days a week at the drug store where he is employed as an assistant manager to keep up with the house payment. With their newly blemished credit record, the couple hasn't yet been able to refinance out.

"We want to keep our house," says Jemima. "But we can't do it with the mortgage we have right now."

__________________________

Scary Math: More homes, fewer buyers

Home prices: No quick rebound

The risk in subprime