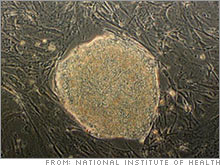

Stem cell industry set to break outWith California finally free to spend $3 billion on embryonic research, the stage could be set for a hot new biotech sector.NEW YORK (CNNMoney.com) -- Two recent developments in embryonic stem cell research have fueled talk of a budding new industry waiting to explode. First, after a lengthy court battle, California last month won the right to spend $3 billion in public funds for research into embryonic stem cell lines. The change is significant due to the ban on federal funding for embryonic stem cell research, enacted amid White House objections to destruction of embryos to create new cell lines.

The industry saw another significant development Wednesday, when a team of researchers published the results of studies in which skin cells were taken from a mouse and reprogrammed to act like embryonic stem cells. If the experiment ever leads scientists to a way to duplicate the results in humans, it would sidestep the thorny ethical questions posed in the embryonic stem cell debate. With the money that will be distributed from California, and the latest development in skin cell research, analysts and the biotech industry see this as a moment that will permanently change industry, science and medicine. "These new studies, done with mouse cells, point the way to experiments that can be tried with human cells and represent some of the most exciting work in stem cell biology and genetic reprogramming," said Harvard Stem Cell Institute co-director Doug Melton in a statement. All the researchers involved, though, stressed that it will take time until the work can be used to benefit humans. Still, it caused optimism in the field. "I think it's fantastic proof-of-concept that you can reprogram mouse cells to go back in time and be like embryonic stem cells. From that point of view, it's another step forward," said Clive Svendsen, co-director of the Stem Cell and Regenerative Medicine Center at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. "The thing it doesn't do is address the sticky issue of whether this can work in human cells." Extending the results to humans will be costly as well, said Svendsen, adding that labs will have to adopt "a different business model if you want to get that done efficiently." Regardless, Robin Young, a private analyst and author of "Stem Cell Analysis and Market Forecasts 2006-2016," sees California's public financing and the rapid progress of the stem cell industry on the whole as comparable to man landing on the moon. "I maintain stem cells will be used in just about every area of medicine and are probably the single most important medical innovation in the last generation," Young said. "As we look back we could never have predicted how big [landing on the moon] was, and I think the same thing is happening here." Stem cells are considered valuable due to their ability to replace other cells and tissues. Advocates say embryonic stem cells, taken from the inner cell mass of a human embryo, often during in-vitro fertilization treatments, are especially useful because of their ability to develop into nearly any tissue in the human body. Adult stem cells, extracted from a variety of tissues and organs, are less adaptable. But experts caution that the adaptability of embryonic stem cells is also their greatest danger, in that they can take unwanted forms such as tumors. In the meantime, Young sees sales of treatments and therapies associated with stem cells growing from $30 million this year to $700 million by 2010 and $8.5 billion by 2016. Driving most of that growth for the first several years, though, will be products generated from adult stem cells. Even the most ardent supporters of research using embryonic stem cells concede that marketable products are up to a decade away, due to the time needed for research and navigating the difficult path toward Food and Drug Administration approval. Despite their touted promise in treating Parkinson's Disease, diabetes and other ailments, embryonic stem cells have yet to yield any treatments or therapies. But with Osiris Therapeutics on the cusp of FDA clearance for its stem cell-derived treatment for Graft-Vs.-Host Disease, a painful condition brought about when bodies reject transplants, the momentum for the stem cell industry is just beginning, Young said. If you fund it, they will come Couple the new medical developments with the availability of government research funding, and private money will follow. The $3 billion California is providing will only go so far, and competition for the funds among research labs and private companies will be keen. And while it will be distributed over a 10-year period, the money is seen as a vital first step. "I think you will start seeing private money start flowing," said Joydeep Goswani, vice president of stem cell research at Invitrogen, a research lab. "That $3 billion, it will change the industry as a whole. I have no doubt about that." Young sees Geron (Charts) as being the leader in embryonic stem cells, with Osiris (Charts) and Cytori Therapeutics (Charts) prominent in the adult stem cell field. Other expected players include Invitrogen (Charts) as well as Orthofix (Charts) and Nutech. California voters approved Proposition 71 in 2004, but the initiative had been on hold pending a legal challenge from a consortium of anti-abortion groups who argued, among other things, that the process for awarding public funding would be compromised because of conflicts of interest among those who will decide where the funding will go. The law sets up the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine, a clearinghouse for the grants and loans created through Prop 71. The institute will be governed by officials from California's state-funded institutions, many of which will be vying for research funding. University officials are required to recuse themselves from votes involving their institutions and Prop 71 funding. But getting California funds, which won't cover much beyond preliminary research, just might be the easy part. Finding the private capital to bring stem-cell products to market is where it gets tough, especially with a science as unproven as embryonic research. Dr. Marc Headrick, president of Cytori, said his company's development in the stem cell field began in laboratories at UCLA and the University of California-San Diego. When executives could start to think about bringing products to market, they needed to raise $50 million just for regulatory filings and protecting intellectual property. Only a solid business plan allowed the principals at Cytori to move forward. "You really need a corporate infrastructure to take it to the next level," Headrick said. "That kind of capital investment and that kind of expertise are not found in the academic environment. And very few companies are willing to make a bet that early until there's proof of concept." Still, there's plenty of interest in getting in on the field, and other states are following California's lead into providing public money for the fledgling industry. Maryland, for instance, has allocated $38 million over the past two years and has approved 24 applications, all but one academic in nature, for grant money. New York, New Jersey and Illinois also have tiptoed into the field, with New York allocating $100 million this year for research. Most of that money is not specifically targeted toward embryonic stem cell research per se, though California's Proposition 71 clearly indicates projects that would not be funded by the federal government - i.e. embryonic research - will get priority. The CIRM on Tuesday awarded more than $50 million in grants to various researchers, with the big winners being Stanford University and the Buck Institute for Age Research, both of which received more than $4.1 million to finance construction of shared research laboratories. Susan Solomon, founder and CEO at the privately funded New York Stem Cell Foundation, a nonprofit dedicated to research in the field, acknowledged the long road ahead for embryonic stem cell advocates but said public money is essential to get things moving. And like others in the field, she counseled patience from those who expect the investments from California and other states to yield immediate results. "There's pressure from advocates for results now, which is not necessarily a bad thing as long as it's tempered with the understanding and reality that scientists are working as hard as they can," Solomon said. "Things have been politicized and we look for sound bites in an area that's very complicated and doesn't lend itself to sound bites." The analyst Young said he doesn't see public impatience with developing embryonic stem cell treatments as a deterrent to the industry's growth. He believes that once any stem cell treatments hit the market, consumers won't differentiate over whether they came from adult or embryonic stem cells. |

Sponsors

|