A chocolatier's sweet successHow Frank Crail climbed the great chocolate mountain.(FSB Magazine) -- Back in the early 1980s, Frank Crail had a dream that many of us harbor in some small corner of our souls. A successful - if harried - tech entrepreneur in sunbaked Southern California, Crail yearned for a small town in the cool mountains where he and his wife could raise a big family and savor the simple life. So he moved to Durango, Colo. (pop. 15,000), and started looking around town for a way to make a living. "I realized I had two options: a car wash or a chocolate store," Crail recalls. "I'm not a car-wash kind of guy, so I opened the chocolate factory."

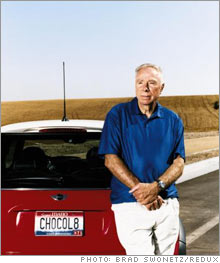

Crail wasn't exactly a candy man, either. He mixed his first batch of chocolate on a Ping-Pong table and got it all wrong. The nut clusters were as big as hockey pucks. The peanut-butter cups were a size D. But it turned out that folks were hankering for supersized sweets. Crowds gathered, and not just for the chocolate. Part of the fun was watching the new shopkeeper fumble around in his open kitchen. Today Crail's Rocky Mountain Chocolate Factory (Charts) is the largest U.S. chocolate retailer in terms of locations, surpassing Godiva and See's. Rocky Mountain (rmcf.com) has 325 stores in 44 states and this year plans to open 40 more. Revenues rose 13 percent, to a record $31.6 million, in fiscal 2007. (Same-store revenues, however, were flat.) Profits climbed 17 percent, to an all-time high of $4.7 million, propelling the company to No. 80 on the FSB 100. "Rocky Mountain Chocolate is a virtual cash machine," says Jerry Falkner, chief executive of R.J. Falkner & Co., an investment research firm in Spicewood, Texas. "Frank Crail finally figured out the chocolate business, and he's minting money now." (Falkner's company has no relationship with Rocky Mountain.) Crail's early years were, to be sure, rocky. Eager to ride his first store's success, he opened in Breckenridge and Aspen. Then an old friend opened a franchise in Colorado Springs. Over the next two decades, Rocky Mountain opened franchises and company-owned stores all over the U.S. and in Canada. "Resort towns are perfect for chocolate," Crail says. "No one's on a diet when they're on vacation. People have money to spend, and they've got to bring something to folks back home." But lickety-split growth proved tough to manage. Money was always tight, making it hard to recruit experienced executives. The company ricocheted through the 1980s and 1990s, sometimes profitable but quite often not. But the growth continued. Crail signed a dozen leases with outlet malls but couldn't recruit franchisees quickly enough. Soon Crail was managing more than 52 shops himself while launching a second chain of 13 hard-candy stores, Fuzziwig's. In retrospect, he says, "we didn't have the infrastructure to handle them." Whitman's Candies offered to buy Rocky Mountain for $16 million in 1999. Tempting - but Crail refused and vowed to turn his company around. By then he had recruited a CFO from autoparts retailer Super Shops. Rocky Mountain closed unprofitable stores, sold off Fuzziwig's, and put itself on a strict fiscal diet. Today the company has no debt and pays an annual dividend of 40 cents a share. Crail also focused on recruiting business-minded franchisees who today would have to shell out an average of $250,000 to buy in. "Chocolate is full of hobbyists," says Ken Nisch, chairman of JGA, a retail design firm in Southfield, Mich., that counts Godiva, Lindt and Rocky Mountain among its clients. "Rocky Mountain has been careful to identify franchisees who understand that it takes hard work to run a successful store." That was a key lesson. Says Crail: "A chocolate shop is not a get-rich-quick scheme." These days Crail, 65, is often on the road searching out new locations. So much for his dream of a simple life, though he did make good on one wish: He raised seven children in Durango. Every one of them, he says, makes darn good candy. |

Sponsors

| ||||||||||||