Samsung's identity crisisThe giant Korean electronics manufacturer shed its image as a purveyor of cheap knockoffs long ago. So why doesn't it get more respect over here?(Business 2.0 Magazine) -- One day in the not-so-far-off past, Kun-Hee Lee, chairman of Samsung Electronics, sent each of his closest friends and key employees one of the company's newest wireless phones as a New Year's present. It was a nice thought, but it backfired. The things just didn't work properly, and polite complaints started pouring in. Mortified, Lee rushed to the company's factory in the South Korean city of Gumi, where most of Samsung's handsets are made.

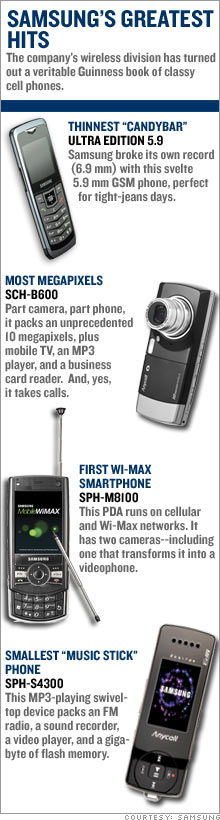

He gathered the employees in the courtyard, made a giant heap of the factory's entire inventory of wireless phones -- more than $15 million worth -- and ordered it smashed to pieces and set on fire. The incineration at Gumi marked a turning point in Samsung's turbulent history. Before 1995 the company was known primarily as a purveyor of cheap knockoff electronics. Afterward, the emphasis shifted dramatically. R&D spending increased. Quality management and technology innovation took on new importance. Assembly-line workers were given new marching orders and regulations, such as a "line stop" system whereby employees could shut down the production line if they discovered inferior products slipping through. Today the problem with Samsung mobile phones is almost the opposite of the situation that day in Gumi. The company has turned out a veritable Guinness book of technological marvels: the world's first MP3 phone, the world's thinnest phones, the highest-megapixel camera phone, the first Wi-Max phone. But it has yet to produce a single runaway best-seller -- an "it" phone -- or establish a brand name that screams "cell phone!" the way Nokia (Charts) or Motorola (Charts, Fortune 500) does. And now, as the company struggles to grow its meager cell-phone market share in the United States and prepares to move into the fast-growing Indian and Latin American markets (which Nokia has already started to flood with low-cost phones), Samsung's technological edge may be hindering its growth. "Samsung always has the newest, most advanced products," says Tina Teng, a wireless analyst at iSuppli, a research firm based in El Segundo, Calif. "But it needs a signature product -- something that will make its brand name stick in consumers' minds." In other words, mighty Samsung Electronics -- a $63 billion multinational that operates in more than 50 countries and dominates high-tech industries from TVs and LCD screens to DRAM and flash memory -- is suffering an identity crisis. Samsung doesn't have identity problems at home. In South Korea, its Anycall phones are as ubiquitous and identifiable as Apple's iPods are in the United States. Drive through Seoul's crowded streets and you'll see superconnected Koreans using Anycalls to listen to music, pay their bus fare, upload pictures to Cyworld (a popular networking site), and even occasionally make a phone call. In the city's trendy Shinchon district, Samsung's Anycall Studio has become a fashionable afterschool hangout. Every weekday afternoon Korean schoolgirls flock to the two-story electronics showroom to listen to music, disinfect their cell phones, and play with Samsung's latest gadgetry. On a recent day, about a dozen girls in short plaid skirts and bright-colored Converse high-tops crowded around one of the shop's most popular toys: a 10-megapixel camera phone. They took turns posing and snapping photos and then giggled as the pictures, beamed via Bluetooth, spewed out of a nearby printer. In less time than it takes a Polaroid to dry, the girls moved on to the next attraction: a multiplayer mobile gaming station on the other side of the room. To these gadget-happy Koreans, Samsung's phones are as commonplace as kimchi, the spicy condiment they eat like candy. In fact, according to U.K.-based research firm Analysys, 86 percent of the inhabitants of this small mountainous nation own mobile devices, and a whopping 90 percent of them use data services like e-mail, the Web, and live mobile TV. Their phones of choice: Samsung's Anycalls. Outside Asia, however, identifying a Samsung handset is not so easy. Peel the labels off a couple dozen cell phones and lay them on a table and you could probably pick out the Nokias and the Motorolas. The Samsungs? Not so much. The job of making Samsung cell phones as famous abroad as they are at home falls to Geesung Choi, 56, a marketing expert and a rising star in the company who took Samsung's TV business from No. 6 in the world in 2001 to No. 1 today. He's the first executive without a background in technology to be put in charge of the mobile-phone division, but the company is counting on him to do for cell phones -- which account for 31 percent of Samsung's revenue -- what he did for televisions. In his first public appearance, at February's 3GSM wireless show in Barcelona, Choi told his audience how he planned to reshape his division within a year. At the top of his agenda: pushing into fast-growing emerging markets (which Samsung had studiously avoided) and creating an emotional connection with customers. Samsung's timing couldn't be better. Troubles at Motorola -- which posted a $181 million first-quarter loss earlier this year -- could soon put the two companies neck and neck for the No. 2 position in global market share, behind Nokia's 36 percent. Building Samsung into a beloved brand in one year will be no small feat, even for Choi. And doing it in emerging markets could be tricky. As Nokia's and Motorola's evaporating profit margins suggest, selling phones in the developing world is a dangerous game. But considering where Samsung started and how far it has come, anything is possible. Founded in the late 1930s as a tiny exporter of dried fish and fruit, Samsung -- "three stars" in Korean -- began diversifying early on. It sold its first black-and-white TV in 1972 and manufactured its first cell phones in 1988. But due to dodgy quality, the phones failed to catch on, even on Samsung's home turf. In the early 1990s, Motorola's analog phones -- not Samsung's -- dominated Seoul's billboards. All that changed after the Gumi bonfire. Lee's new emphasis on quality helped, but what probably mattered more was his lucky bet on digital. Samsung never quite caught up to its rivals in analog mobiles, but its early investment in digital technology paid off big-time in the late 1990s, when the industry began switching to 0s and 1s. Finally, it was Samsung's turn to shine. In 1997 the company signed what was at the time the single largest contract for handsets: a $300 million deal to supply U.S. mobile operator Sprint (Charts, Fortune 500) with advanced CDMA phones. "In the past, we were considered a follower," says senior sales and marketing VP Jeonghan Kim, sitting in a posh, air-conditioned office in Samsung's corporate headquarters. "But today we are a leader." Samsung is a smart company. While it hasn't had the reach of Nokia and Motorola, its profit margins have held up better; earlier this year, when the top two phonemakers announced lower-than-expected profits, Samsung disclosed that its margins had risen to 13 percent, up from 7 percent the previous quarter. Still, the deep investment in technology that helped Samsung dominate Korea makes it harder for the company to break into less sophisticated markets, from which 85 percent of all handset shipment growth is expected to come in the next three years. "Most networks aren't even ready for a lot of their phones," says iSuppli analyst Teng. The United States, for example, doesn't have broad support for TV-playing phones, and high-speed 3G networks are a nonstarter in much of the Third World. On the other hand, millions of people are shopping for their first cell phone. In India alone, an estimated 6 million people buy their first handset each month, according to analysts at the Mobile World. That's why Nokia and Motorola, despite razor-thin profit margins, are battling for market share there. Each hopes that selling dirt-cheap handsets today will position it as the phonemaker of choice tomorrow, when those millions of customers start buying more advanced phones. Choi is taking a different approach. He, too, wants to enter the Third World, but on his own terms. Rather than sell cheap starter phones, he's catering to the high end of the low-end market -- the "premium low end," as the company calls it -- selling phones with a few bells and whistles in the $50 to $70 range. "We aren't going to move away from premium to fight it out in the commodity sector," says David Steel, a Samsung marketing VP whom Choi brought over from the TV division. "The new emphasis is on recognizing that what constitutes 'premium' can be quite different in different countries." That means fewer phones with built-in GPS, MP3 players, and mobile browsers and more phones that sell themselves through innovative designs and distinctive colors. The company has brought in a small army of industrial artists, cognitive scientists, and sound engineers to compose ringtones and design color palettes that include hues like "glazed chocolate" and "chic silver." The hope is that by paying careful attention to both form and function, Samsung can differentiate itself even in the simplest of phones. The attention to Samsung as a brand is part of a companywide effort that Lee initiated in 1996. Since then, its designers and marketers have worked to extend the "essence" of the brand across the company's product lines. When you use a Samsung device, whether you're in Boston or Bangalore, it's supposed to have the same look, feel, and even sound. In 2005, for instance, Samsung began a global marketing campaign that included a series of "Imagine" TV ads that closed with the Samsung logo and a distinctive sound effect. Today, when you turn on just about any Samsung product, it will display that logo and make a similar sound. Not surprisingly, one of the first things Choi did when he took over cell phones was to bring the division's engineering and product marketing people under one roof. Today they all work together at the company's nearly 2 million-square-foot headquarters in Suwon, a muggy industrial city just south of Seoul. Choi hopes the synergy between product marketing and R&D can spur the development of new phones that say, "Buy me. I'm a Samsung." "When Samsung handsets become emotional icons," writes the press-shy Choi in an e-mail, "I will have achieved my goal." The consumer-centric approach can already be felt in the United States, where instead of hawking phones with forgettable names like VM-A680 and SGH-S307, Samsung is putting its considerable marketing muscle behind a smartphone called BlackJack and a dual-face music phone called UpStage. But creating brand loyalty is an uphill struggle this summer, and not just because of the high-decibel buzz surrounding the latest droolworthy gadget from the folks at Apple. BlackJack has reportedly been selling at the rate of 100,000 units a month, but most Americans still don't know that it's a Samsung. "For a long time, our core competency was manufacturing, and now we're clearly going off to the marketing world," says VP for strategy Peter Skarzynski. "Creating a bond with consumers is a new thing for us." But it can be done, as demonstrated after school every day by the revolving door of hip young Koreans scrambling to get their hands on the shiny gadgets in Samsung's Anycall Studio. The trick for Choi will be to get other young cell-phone users -- American, Latin American, Indian -- to love his products as much as these kids do. Michal Lev-Ram is a staff writer at Business 2.0. |

Sponsors

|