Risk returns with a vengeanceFor years big players ignored obvious dangers and reaped rich rewards. Now they are paying the price - and so is everyone else, writes Fortune's Shawn Tully.(Fortune Magazine) -- For the past five years risk has been the invisible man on Wall Street. Banks, hedge funds, and lenders behaved as if home prices always rise, borrowers never miss a payment, and companies never blunder into bankruptcy. Now a crisis of confidence that began with subprime mortgage defaults is sweeping the Street, and risk is invisible no more. Banks are wobbling, markets are quaking, and ordinary investors are wondering how badly they'll be hurt. Risk, as always, will exact its revenge.

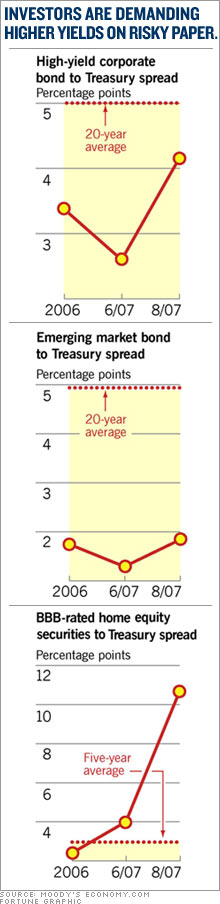

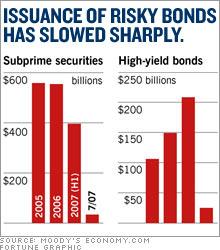

Already signs of carnage abound. Nervous lenders have driven up interest rates on all debt other than U.S. Treasuries, making it hard for many financial companies to fund their operations. In mid-August the nation's largest mortgage lender, Countrywide Financial (up $1.04 to $22.86, Charts, Fortune 500), was forced to tap its lines of credit to stay solvent, a dire move that rattled investors. KKR Financial, an affiliate of the buyout firm, reported that it could lose more than $200 million on its holdings of mortgage-backed securities. Highbridge Capital, a unit of J.P. Morgan (down $0.54 to $45.46, Charts, Fortune 500), saw its Statistical Arbitrage fund fall 18% in the first eight days of August. A raft of private equity deals are on hold or being renegotiated, including Home Depot's (Charts, Fortune 500) sale of its building-supply subsidiary to Bain, Carlyle, and Clayton Dubilier & Rice. There have been signs that even supersafe vehicles like money market funds may not be immune. The Federal Reserve has made extraordinary injections of more than $62 billion into the financial system to keep credit flowing. The European Central Bank has pumped in almost $300 billion. Tight money isn't just a problem for Wall Street heavyweights. The stock market, spooked by the prospect of bankruptcies and defaults, has fallen 8% since mid-July, dinging ordinary investors and taking a bite out of their 401(k)s. Volatility is becoming a way of life. Investors who had grown accustomed to a smooth upward climb in stock prices are numbly witnessing downward swoons of 200 or 300 points a day as rumors about this hedge fund or that mortgage lender set off waves of selling. The credit crunch has raised the cost of mortgages even for borrowers with pristine credit and put further downward pressure on home prices. David Adamo, CEO of Luxury Mortgage, a mortgage banker in Connecticut, says that three months ago he could sell a high-quality $3 million mortgage to 20 different banks at an interest rate of 6.75%. Today only two will even consider buying the loans, and they want 10%. The real worry is that a more drastic meltdown may lie ahead. It might begin, for example, with the collapse of a marquee hedge fund. The banks that extended billions of dollars in loans to the fund would suffer deep losses. Other lenders, girding for a wave of defaults, would turn off the tap. "A big problem is that lenders don't know which of their clients is likely to default because the system is so opaque," says Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody's Economy.com. "So they would stop lending to everybody." Even rock-solid companies like Procter & Gamble (Charts, Fortune 500) or IBM (Charts, Fortune 500) will have to pay more to borrow money to build new plants or make acquisitions. That's when the crisis could jump from the markets to the economy at large -- crimping business investment and consumer spending and bringing on a painful recession, with job losses, sharper stock market drops, and even steeper declines in home values. For the moment that's still the worst-case scenario, not the most likely one. No one knows when the market turmoil will end or where it will lead, but in this special report we'll tell you everything you need to know to understand the market shock and its potential consequences. We'll examine the origins of the crisis and explain what the return of risk means -- to the markets and individuals. A gallery of market veterans, including legendary investors Warren Buffett, Bill Miller, and Bill Gross, assess the turmoil and advise investors in their own words on what to do about it. Further on, we'll look at how the subprime mess ensnared a German bank, and we'll show its impact on that most precious of assets, your home. Put simply, what we're seeing is a massive repricing of risk in every asset class, from mortgages, junk bonds, and high-grade corporate debt to office buildings and equities. Suddenly investors have recognized that they weren't getting paid nearly enough for the perils of owning securities backed by dubious mortgages and low-rated bonds. The root cause of the current problems, says Jeremy Grantham, chairman of investment company GMO, "is that risk was mispriced on an extensive basis globally." Now investors are demanding far bigger compensation for putting their money on the line. The compensation they want is higher interest payments on debt and increased returns on stocks and real estate. And in the inexorable mathematics of the markets, for investors to get better returns in the future, asset prices have to drop substantially. Fortunately, this upheaval is taking place at a time when the basic economic outlook remains sound, bolstered by low inflation and strong growth around the globe. The best bet is that asset values will settle at a level higher than their long-term averages, reflecting the generally balmy climate. The rub is that prices have been bid so high that in many cases they still have quite far to fall; we'll give our estimates of how much a bit later. One hint: Stocks still look overvalued by at least 10% or so. "The prices of stocks, bonds, buildings, and the like were bid extremely high," says Yale University economist Robert Shiller. "That's why we could be near a major inflection point." The credit crisis has its roots in a world awash in cash. In the aftermath of the 2000 stock market crash, Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan cut short-term interest rates to historic lows to stoke consumer spending and prevent a recession. Greenspan's gambit worked, if anything, too well. The U.S. economy kept moving smartly, filling corporate coffers with record profits, even as the stock market continued to slump. Greenspan's moves triggered an explosion in global liquidity. Central banks from Britain to Japan followed his lead and pumped money into their banking systems. Insurance companies, mutual funds, and pension plans all over the world used their cheap money to buy assets in the world's most stable economy, the U.S. At the same time China's roaring export boom brought in a flood of dollars that China sent right back to the U.S., mainly by buying Treasury securities. The result was a remarkably benign economic environment. Inflation was low. Corporate profits soared. Economic growth around the globe followed a smooth, ascending curve. "We've never seen a world economy like it, where volatility practically doesn't exist," says renowned economist Peter Bernstein. Sounds great, doesn't it? But there was a catch. The strong, stable global economy began to lull investors into a false sense of security. They began to behave as if the chance of losing money had all but disappeared. You can see it clearly in the narrowing of risk premiums -- the extra yield that investors typically demand for holding mortgage bonds and low-rated corporate debt. In early 2001, for example, the average junk bond yielded 9.3 points more than the ten-year Treasury bond. By 2005 that gap had narrowed to four points -- and it kept shrinking. "Risk premiums hit a record low back in February," says Grantham. "They were probably at the lowest point in history and across a very broad base of assets." That indifference to risk would have severe consequences. "People showed a new fearlessness about borrowing cheap money," says Bernstein. Indeed, cheap money made the leveraged-buyout boom possible. With stock prices lagging, private equity firms made lush profits by borrowing money to buy companies like Hertz (Charts, Fortune 500), cleaning up their operations, and selling them back to the public (or another private equity shop) a few years later. The success of early deals emboldened the players, who were soon paying higher prices for the companies they acquired and borrowing more money to complete the deals. Rock-bottom interest rates also helped Americans pursue their love affair with real estate. Housing activity exploded: New construction, sales of new and existing homes, and of course prices all hit unprecedented levels. The euphoria had its usual effect. Rather than prudently thinking "it can't last," more and more people came to believe real estate was a no-lose investment and borrowed heavily to buy bigger and better homes, confident that they could always turn around and sell at a profit if they needed to get out. All this borrowing was especially lucrative for Wall Street investment banks. Goldman Sachs (down $0.70 to $177.19, Charts, Fortune 500), Morgan Stanley, Merrill Lynch (down $0.70 to $75.74, Charts, Fortune 500), and others generated fat fees by underwriting huge volumes of mortgages and the loans and junk bonds that funded LBOs. For example, the standard fee for underwriting LBO loans is 1.5%, meaning that firms that raised $10 billion in debt pocketed $150 million. The fees on junk bonds were even higher. The Wall Street houses wouldn't have underwritten all that debt if they hadn't been sure they could sell it quickly. And sell it they could. Their biggest customers were entities known as CDOs (collateralized debt obligations) and CLOs (collateralized loan obligations). Although the names make them sound like financial instruments, they are actually investment funds, typically operated by hedge funds or banks. CDOs buy bonds, including high-yield issues and mortgage-backed securities, while CLOs purchase corporate loans, including those used to finance buyouts. The CDOs and CLOs turn around and sell a variety of bonds backed by the payments on the loans and the collateral securing them, such as houses, plants, equipment, and inventories. Who buys those bonds? They were extremely popular with foreign investors, from Chinese banks to Dutch insurance companies. Those investors tended to buy the paper with the highest ratings -- that is, the bonds that had first claim on the cash flow and collateral backing the loans. The hungriest buyers, though, were hedge funds scrambling to deliver market-beating performance. They tended to take the lower-rated, higher-yielding paper and then juiced the yields by buying on margin. That enabled them to give their clients -- endowments, pension funds, wealthy individuals -- supercharged returns of 20% or more. And guess who loaned those hedge funds the money to buy the loans on margin: the prime brokerage arms of the same investment banks that underwrote them. Caution vanished. The Wall Street money machine was in overdrive. The Fed tried to put on the brakes, raising short-term interest rates from a record low 1% in 2003 to 5.25% by mid-2006. Central banks from the European Central Bank to the Reserve Bank of Australia followed suit. The rate hikes threatened to put a serious dent in Wall Street's profits. For one thing, higher mortgage costs finally began to have an impact on home sales, which meant that the investment banks faced a sharp dropoff in home loans to underwrite. And higher rates were likely to dampen the LBO business as well. But the investment banks found a way to keep business rolling. They loosened their credit standards, agreeing to purchase far-lower-quality loans. The effects were dramatic. Knowing that Wall Street stood ready to buy up almost any kind of mortgage, lenders started ladling out cash to homebuyers with poor credit histories who had very little hope of paying it back. In 2005 and 2006 the volume of subprime mortgages exploded. The loans often included seductive features such as teaser rates that doubled or tripled after a year or two, or low monthly payments that didn't cover the full interest charge (the unpaid interest would be added to an ever-rising loan balance). Lenders also increasingly allowed homebuyers to borrow money for the down payment with so-called piggyback loans. The aggressive practices helped create a new, high-risk stratum of homeowners who simply couldn't afford their houses and were bound to default in large numbers. Sooner rather than later, as it turned out. The players in LBO financing followed the same script. The deals became riskier and riskier as the KKRs and Blackstones bought bigger companies, sometimes after bidding wars that ratcheted up the prices, and piled on debt to cover the cost. Earlier this year KKR agreed to pay $26 billion for credit card processor First Data, borrowing $19 billion to finance the deal. Once the deal closes, interest payments will eat up almost all of the company's cash flow, leaving little margin for error. Here again, instead of slowing the flow of money -- as would have been prudent -- Wall Street relaxed the rules. Companies were regularly granted "covenant-lite" loans that waived the formerly ironclad requirement that they maintain a specified ratio of cash flow to interest payments, ensuring an ade-quate cushion against an industry downturn, say, or a recession. Companies like Univision and Freescale Semiconductor even have the option of making interest payments in the form of bonds, a feature resembling those mortgages where homeowners pile on more debt in lieu of paying interest. Lowering standards worked beautifully -- at least for a while. By 2006 investment banks were collecting almost $6 billion from underwriting mortgages and other loans, 60% more than in 2003. In the first half of 2007, revenues were running at an even faster pace. Investors never balked at buying the dubious paper Wall Street churned out. Incredibly, even as the world got markedly riskier, risk premiums got narrower. Between late 2005 and May 2007 the spread between junk bonds and Treasuries dropped from 3.8 points to a 20-year low of 2.6 points. Party on, dudes! The end seemed to come suddenly, but there had been plenty of warning signs. One banker describes how he and his colleagues were caught off-guard. "We're not dumb -- we knew it would happen sometime," he says. "But not in August and not this swiftly. Plus, subprime? We thought we'd dodged that bullet." Indeed, defaults and delinquencies on subprime mortgages began rising in mid-2006. The markets shrugged off the news. In February of this year, HSBC (down $0.89 to $89.86, Charts) reported a loss of $1.8 billion on its portfolio of subprime loans. Rates on mortgage-backed securities rose, small lenders went under, but still the stock and bond markets barely noticed. In June investors got an even clearer signal of trouble ahead. Bear Stearns (Charts, Fortune 500) announced problems at two of its hedge funds that would cascade into losses of $1.4 billion of their investors' money. Yields on every form of debt started to shoot skyward. Yet even then, stock investors continued to hope that the crisis would pass. In mid-July, two days after the Bear Stearns announcement, the Dow Jones industrial average hit an all-time high, topping 14,000 for the first time. The pace of bad news picked up. The German government had to bail out a bank; BNP Paribas suspended activity at three funds holding asset-backed securities; American Home Mortgage shut down. Stock prices finally began to tumble, with the Dow dropping below 13,000 by Aug. 15. Risk was back, with a vengeance. What does the return of risk mean for the markets? Let's start with private equity, a sector that's heavily influenced by rates on high-yield debt. Since May, the spread between junk bonds and Treasuries has jumped from 2.6 percentage points to 4.6 points. Not only does that throw a wrench into pending deals, it also lowers the value of the companies that are already in the portfolios of a Bain or a KKR. The owners aren't typically allowed to sell their companies with the cheap debt they took on a year or two ago. Hence, a new buyer has to borrow all-new debt, at far higher rates, to purchase them. The higher interest burden cuts net cash flow, reducing the value of the company. A prospective buyer will react like a homebuyer facing higher mortgage rates: It will offer less for the companies. Look for private equity firms to deliver extremely low returns to their investors over the next few years. It's the same story in commercial real estate. The market for office buildings, hotels, and apartment towers has been breaking all records, and for the same reason home prices have ballooned: Investors simply don't think there's much chance vacancies will rise or competitors will crowd hot markets like New York and Boston with new buildings. But commercial real estate, like private equity and housing, depends heavily on the price of debt. And as interest rates rise, the cash flows going to investors drop, pounding prices. "Commercial property values will decrease, and it's pretty simple to see why -- because of the rising-interest-rate environment," says Will Marks, a hotel industry analyst for JMP Securities. For housing, rising mortgage rates are bound to deepen the slump. Since May the rates on jumbo loans (those over $417,000, which can't be sold to Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac) have jumped by ¾ of a point. Customers with poor or mediocre credit histories can't get loans at all, a big shift from a year ago. Before the recent rise in rates, Zandi of Economy.com was predicting that national housing prices would fall another 5% over three to five years on top of the 5% they've already dropped. Now he's doubling that estimate to 10% and predicting additional declines of 20% or more in markets like Miami and Las Vegas. How about stocks? Equity prices have risen, but not to bubble levels. To be sure, the pounding that private equity is taking will put a damper on stock prices, since the huge premiums these firms were paying helped drive equities upward. The problem is that the risk premium on stocks still appears too low. Ready for some math? The equity risk premium is the difference between the Treasury rate, adjusted for inflation, and the expected return on stocks. Typically you calculate the expected return on stocks by looking at the earnings yield, which is the inverse of the market's average price/earnings ratio. We'll spare you the details; today the risk premium comes in at 2.8%, about a point below its historical average. For the risk premium to return to normal, stocks would have to fall an additional 10% or so. That wouldn't be pleasant, but it wouldn't be a crash either. Maybe you feel as if you've seen this movie before? In some sense, all financial bubbles are alike. They begin with abundant cash and sound economic fundamentals. People start racking up gains, and more players pile in, eager to grab a share of the loot. Then they get carried away. It always ends in tears. The good news is that before too long, investors will see something that's been absent from financial markets for years: an appealing assortment of bargain-priced stocks and bonds. As the markets tumbled in mid-August, a young man riding the New York City subway in shorts and sandals flipped through the pages of How to Make Money on Foreclosures. You don't have to be a Wall Street titan to see that the return of risk was necessary, inevitable -- and hey, it may even make you some dough. Reporter associates Katie Benner, Telis Demos, Corey Hajim and Bethany McLean contributed to this article. |

|