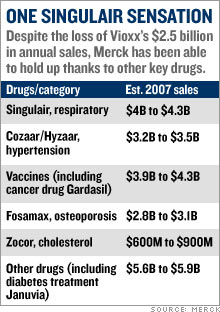

Merck's post-Vioxx comebackStock Spotlight: Merck has had a Lazarus-like turn-around thanks to cost-cutting, new products and a savvy legal strategy. Is it still a buy?NEW YORK (CNNMoney.com) -- Merck has enjoyed a strong comeback since the messy Vioxx blowout nearly three years ago. But you might be surprised by how well Merck has done since it pulled its arthritis drug from the market. Merck & Co., Inc. (up $0.10 to $50.02, Charts, Fortune 500) bears little resemblance to the battered drug company it was three years ago. The stock is up 12 percent from its pre-Vioxx withdrawal levels.   And shares are up 16 percent year-to-date, making it the second-best performing Big Pharma company in the S&P 500, behind only Schering-Plough (down $0.05 to $30.10, Charts, Fortune 500), and leaving competitors like Pfizer Inc., (down $0.09 to $24.58, Charts, Fortune 500) Eli Lilly & Co. (up $0.38 to $56.70, Charts, Fortune 500) and Bristol-Myers Squibb (down $0.15 to $28.86, Charts, Fortune 500) in the dust. Merck has come a long way since Sept. 30, 2004, when it pulled Vioxx off the market after a study linked the anti-inflammatory drug to increased risk of heart attack and stroke. Merck bid farewell to its $2.5 billion-a-year blockbuster, and opened the doors for tens of thousands of lawsuits from former Vioxx patients and their families. Merck instantly became the poster child for Big Pharma's woes. The stock plunged 40 percent within a couple weeks. The company then suffered through a volatile 2005 -- the year that Richard Clark succeeded Raymond Gilmartin as chief executive - before beginning its comeback last year. Loyal investors who held Merck's stock through its darkest days are now better off than they were before the Vioxx withdrawal. Gutsy investors who bought Merck stock near its post-Vioxx bottom in November 2004 have doubled their money. "Everyone now is in great spirits, [while] right after the Vioxx withdrawal, things were looking pretty bleak," said Jon LeCroy, analyst for Natixis Bleichroeder. But can Merck continue to deliver now that the worst seems to be behind it? 'Brilliant' legal strategy When the Vioxx lawsuits started piling up, analysts projected, on average, some $30 billion in potential legal liabilities. But three years later, Merck hasn't paid a penny to anyone blaming Vioxx for their heart attacks. The company has won 10 of the 15 lawsuits filed against it and has appealed all the cases it lost. "They're winning 65 percent of the cases," said Joseph Tooley, analyst for A.G. Edwards. "When it's all said and done, I think the ultimate liability is going to be a much more manageable number than was originally anticipated." But Merck still faces nearly 27,000 more cases. That hardly seems like cause for celebration. Nonetheless, Ken Frazier, the company's lead counsel throughout the Vioxx debacle, has forged a simple legal strategy that analysts say has helped Merck escape major damage. He has refused, from the beginning, to consider any kind of mass settlement and has instead vowed to fight the cases one at a time. "Their strategy in fighting every case and being very clear about it, and telling the whole world they were going to fight every case, was a brilliant strategy. Merck is, of course, in a much better position to defend itself than individual plaintiffs trying to take on this organized effort," said Bryan Liang, professor of health law studies at the California Western School of Law in San Diego. Analysts believe this case-by-case strategy prevented some lawsuits from opportunists looking for an easy cash-out to ever make it to trial. So far, 4,650 plaintiffs have been dismissed, according to Kent Jarrell, the spokesman for Merck's outside counsel. "Our core strategy has been examining individual cases," said Jarrell. "The approach is working. We've seen thousands of cases dismissed because the cases, on closer examination, weren't backed by facts." The next Vioxx trial is scheduled for Sept. 17 in Florida Circuit Court in Hillsborough County. Investors want a new drug But Vioxx isn't the only problem for Merck The company has also had to deal with patent expirations on potent blockbusters like Zocor, which peaked at more than $5 billion in annual sales before generic pressure started to erode revenues in 2005. The patent on Fosamax, the $3 billion-a-year treatment for osteoporosis, will also expire next year. Once a drugmaker loses exclusive control over a name-brand drug, revenues typically drop 80 percent. Clark answered the loss of multi-billion dollar products with a multi-billion dollar cost cutting, shutting down several manufacturing plants and eliminating 7,000 jobs. Tooley estimates that the cost-cutting could reach $5 billion, eclipsing the sales vacuum left by Zocor. But that doesn't make up for the impending loss of Fosamax. LeCroy expects Clark to launch another round of fat-trimming in 2007, when the osteoporosis patent fades into thin air. "I expect next year for [Clark] to implement more cost-cutting, because next year they lose their patent on Fosamax," said LeCroy. But investors with an eye on the future aren't satisfied with cost cutting. They want to see growth, which means that Merck has to produce profitable new products. And analysts say much of Merck's recent stock market prowess stems from the success of fast-growing, newly-launched products like the diabetes drug Januvia and the cervical cancer vaccine Gardasil. Merck launched those products in 2006 and both are expected to eventually reach billion-dollar blockbuster levels. Gardasil has been approved in 80 countries and is being reviewed in 40 more. "[The patent loss of] Zocor is being made up with cost-cutting, [while] Januvia and Gardasil alone more than make up for Vioxx and Fosamax," said Tooley, who projects annual sales in 2011 of $3.2 billion for Gardasil and $3.1 billion for Januvia. In addition, Merck has a late-stage pipeline that analysts say is loaded with potential big-dollar drugs, including experimental cholesterol treatment Cordaptive -- which LeCroy predicts could generate $1 billion in an annual sales -- and experimental AIDS drug Isentress (also known as raltegravir). On Sept. 5, the FDA will hold an advisory meeting to vote on whether Isentress merits approval. Merck experts the FDA to make its final decision in mid-October. Tooley projects that Isentress annual sales will reach $750 million by 2011. Merck still looks like a bargain With all this in mind, Tooley said Merck could now actually meet the long-term goals the company set prior to the Vioxx withdrawal, most notably an earnings per share target of $4 in 2010. Analysts currently expect Merck to earn $3.11 in 2007 and $3.24 in 2008. "We think ultimately they'll get to their long-term guidance, which they gave five years ago, and which everybody thought was too high," said Tooley. Despite its gains this year, Merck trades at less than 16 times 2007 earnings estimates. That's in line with the industry average and is lower than the valuations for other Big Pharma stocks with similar growth rate projections such as Abbott Laboratories (Charts, Fortune 500), Bristol-Myers Squibb and Watson Pharmaceuticals (Charts). As such, analysts are bullish on the company's stock. Tooley has a 12-month price target of $54 for Merck, while LeCroy of Natixis Bleichroeder has a target of $58, compared to its Aug. 29 close of $49.92. "We continue to think there's upside from current levels for Merck shares," said Tooley, who believes that the cost-cutting and new product sales will continue to drive the stock. So for all those investors who are kicking themselves for not buying Merck when it was left for dead three years ago, there still may be a chance to take part in the company's comeback. The analysts interviewed for this story do not own Merck shares, but A.G. Edwards has received compensation from the company for non-investment banking services in the last 12 months. |

|