(Business 2.0 Magazine) -- There's a war on bluster, and Fred Franzia is losing. Sure, the CEO of Bronco Wine, the nation's fourth-largest wine company, tells me repeatedly that only a sucker would pay more than $10 for a bottle of wine - including his own $35 Domaine Napa. And that Napa's and Bordeaux's claims about their special soils are bogus: "We can grow on asphalt. Terroir don't mean sh*t." After relieving himself by the side of his Jeep, Franzia recounts a trip to Burgundy where, after an elaborate tasting, he told the winemaker at Ch�teau Haut-Brion, "You can bottle gasoline if you can sell that."

Franzia, who rose to fame several years ago when he started selling a $2 bottle called Charles Shaw, calls winemakers "bozos in a glass." He really goes off on wine critic Robert Parker, who, he says, likes tannic wines that make people gag. He mocks my college ("We buy wineries from guys from Stanford who go bankrupt. Some real dumb-asses from there"), my religion ("A Jew who eats ribs? You impress me"), and my job ("Business 2.0? Hell no, I've never heard of it").

|

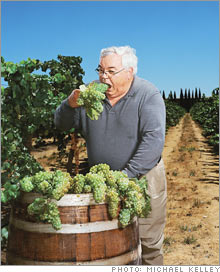

| Fred Franzia: taking a bite out of Napa. |

|

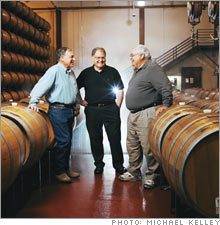

| The Bronco brain trust: Franzia (right) puts in 100-hour weeks with brother Joe (middle) and cousin john, Bronco's winemaker. |

When I ask him about the community service he did after pleading guilty in 1993 to conspiracy to defraud (he sold 5,000 tons of cheap grapes by mislabeling them and sprinkling zinfandel leaves on top), he says of the mentoring of single mothers he was ordered to do: "I picked up on young girls."

But Franzia gets soft real quick. As he drives his Jeep around the vineyards at Bronco's headquarters in Ceres, Calif., a tiny Central Valley town outside Modesto, Franzia admits he'd much rather buy out of bankruptcy court than directly from my hurting fellow alumni, since "it's less emotional."

He keeps stopping the car to look at grape plants like a puttering gardener. He shows me the land where he plans to build his house, complete with a bowling alley for his granddaughter. Looking up at a hawk flying high over his fields, he wonders whether it doesn't have a better life than we do. He tells me he has trouble sleeping. I find, on the passenger side of his Jeep, an Enya CD, which he claims one of his many girlfriends left there. I deeply consider giving him a hug.

But losing the war on bluster isn't a big deal, since it's only one of many wars Franzia is fighting. In fact, he's waging war on everything: gophers, ants, competitors, restaurant chains, stores, the state, the Supreme Court. It's not just his favorite phrase, it's the way he thinks about business. He says it so much, to so many people, that when I talk to his ranch manager, Junior Robles, he starts telling me about the war on weeds.

There's even a war against the guy who rents the portable potties for the field workers: When the guy raised his prices, Franzia went for his sword and shield; he's buying his own portable johns now. "To you, that's a sh*tter," he says, pointing to a blue kiosk. "To me, it's a profit center. It's a sh*tter war. You got to have a war at all times."

But Franzia's main war - the one he's kicking ass at - is against pretentiousness. Bronco, which he owns with his brother Joe and cousin John, has (including vineyard partnerships) 3,000 employees and does an estimated $250 million in annual sales of mostly low-cost wines such as Estrella, Forest Glen, ForestVille, Montpellier, and Silver Ridge. It also gets income from providing distribution, bottling, and juice to other wineries.

In 2002, Franzia persuaded Trader Joe's to sell a low-end label called Charles Shaw (after the winemaker who sold the tony label to Franzia, and dubbed Two Buck Chuck by consumers) that waged war on domestic wines in the $4 to $10 range - and was named best chardonnay in a blind taste test at July's California State Fair over far pricier competition. The label is one of America's fastest-growing, selling 5 million cases per year, all through one chain of stores.

"There's not a doubt in my mind that the two biggest things that have happened to the wine industry in the last 10 years are the movie Sideways and Two Buck Chuck," says Gary Vaynerchuk, who reviews wines on his popular video blog, Winelibrarytv.com. "Has Two Buck Chuck hurt some $8 to $15 brands? Yes. But it's helped the industry overall by bringing in new people. What Franzia is doing, more than creating outrageous quality, is exposing a lot of mediocre people. There are so many fools in the wine industry who are overpriced. Look at Franciscan, Simi, Kendall Jackson. Those guys are jokers."

Much like the Australian powerhouse Yellowtail, Franzia built Two Buck Chuck by buying extensive vineyard property in a cheap area - in his case, the San Joaquin Valley. He bought 35,000 acres stretching from Sacramento to Santa Barbara, the largest acreage of any wine company in the state, to which he's adding three square miles each year. Then he added staggering amounts of bulk wine he scooped up nearly free from other vineyards during the glut that followed the wine boom of the late 1990s.

Once the surplus dried up, everyone thought Charles Shaw would follow. But Franzia has turned it into a sustainable brand, and one that - like Yellowtail or Budweiser - tastes the same every year. That's partly due to his partner and cousin, John, who blends the wine, and partly due to the huge palette of flavors he gets by trading grapes and growing so many of his own. The vintage year printed on the label, Franzia admits, is irrelevant.

Though Franzia is stymied in his next plan to massively change the wine world - by getting restaurants to reduce their enormous markup - he thinks he's on the verge of pushing prices down everywhere else. He's close to getting Wal-Mart to sell one of his labels for $2 a bottle, and he's just started selling a $6 cabernet with grapes from Sonoma's Alexander Valley that he claims he bought from a winery that sells its bottles for $75.

He has four vintages and enough wine for more than 100,000 cases of the brand, which he's calling Alexander & Fitch. He hopes people will see "Alexander Valley" on his label and wonder why they have to pay $20 for other wines from the region. And while he refuses to say this brand is any better than Charles Shaw, when he hands me the bottle, he pauses and says, "Don't just smoke cigars and drink it. Drink it at a great location."

Hating pretentiousness isn't just a business plan. It's Franzia's entire identity. His office is a wood-paneled trailer with carpet holes repaired with duct tape that looks like it might house the night manager of a troubled dude ranch. He uses his cell phone only in his car, and he has no computer; his assistant prints out his e-mail messages in the morning, and he handwrites his responses on them.

He's worked in the wine industry his entire life, but he calls the grapes "varieties" instead of "varietals." For a while, he has me convinced that he's planted some weird grape I've never heard of called "moh-ver-dee," until I realize he's talking about the Rh�ne varietal mourv�dre. Driving by a guy selling fruit along the side of the road in the hot sun might fill some with pity, but Franzia looks on with pride. He pokes me with a thick finger and says, "That's a real businessman."