Why electric vehicles have stalled

Facing technical challenges and a weak market, many of Silicon Valley's electric-car startups are changing direction.

|

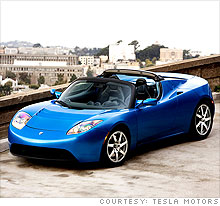

| Tesla Motors has struggled to raise the cash it needs for mass production. |

(CNNMoney.com) -- The Wrightspeed X1, a sports car whose three-second acceleration from 0 to 60 makes it one of the fastest autos in the world, is also super clean: It's powered by an electric motor and gets about 170 mpg. Ian Wright, the Burlingame, Calif., entrepreneur who created the X1 several years ago, had planned on ramping up production on a line of similar electric cars in 2009. But over the summer, he changed his mind.

"It's one thing to build electric cars, but it's another to go out and get some kind of respectable market size and funding," Wright says. "At this stage of the game, when oil is cheap and batteries still expensive, spending two to three -times the price on an electric car doesn't really make sense."

In a 180-degree turn from where his company, Wrightspeed, was a year ago, Wright has completely abandoned the concept of bringing an electric car to market. Instead, while he waits for the electric vehicle market to mature, Wright is focusing on a more lucrative venture: Wrightspeed will make and sell electric powertrains - the battery pack, software, and other components that generate power to a vehicle - to existing car and truck manufacturers, targeting the sports car market, the military, and fleet operators, whose vehicles need lots of short-burst power but travel relatively short distances.

"We're not looking at GM (GM, Fortune 500) or Tesla Motors," says Wright. "Electric vehicles for the mass-market - that's at least 20 years away."

While the climate for energy-efficient electric vehicles is better now than it was a few years go, there are still a number of barriers that clean-tech auto makers must overcome before they'll post significant seals numbers. The challenges include primitive technology, dried-up venture capital, wavering consumer demand, and looming competition from large auto makers in Detroit, Germany, and Japan.

As a result, Wrightspeed isn't the only electric car upstart shifting gears; many of the dozen or so Silicon Valley companies that were trumpeting their roll-outs late last year have delayed production, been taken over by investors or big-industry veterans, or have gone out of business.

"I don't see how the small car makers can survive when you think about the complexity of putting together cars and marketing them," says Doug Scott, a senior vice president at GfK Automotive, a research firm based in Detroit. "The whole notion of setting up a mini-car company - which Tesla Motors is a poster-child for - is easier said than done."

Perhaps the biggest problem the mini-manufacturers face right now is the credit crunch. Although venture- capital investment in the U.S. clean-tech industry hit a record $1.6 billion in the third quarter, most of the money went to biofuel firms and energy-generation companies. Tesla Motors, the San Carlos, Calif., startup that makes the luxurious, battery-powered, $109,000 Roadster, was unable to raise the $100 million it needed to develop the Model S, its four-door sedan that was due out 2010. Instead, Tesla has delayed the electric car's debut until 2011 - a year after the Chevy Volt is scheduled to launch - while it waits for a low-interest Department of Energy loan, due in six months.

"The global financial system has gone through the worst crisis since the Great Depression," Elon Musk, Tesla's CEO, said in a written statement. "It's not an understatement to say that nearly every business will be impacted, and this is true for Silicon Valley as well."

So far this year, Tesla has received 1,200 orders for its Roadster but shipped only 50; the company stalled when it ran into problems with its transmission. Musk, one of Tesla's original investors, took over the CEO position in October, cut the company's workforce, and raised $40 million in convertible debt, part of which he's using to develop a battery with a better range. He says that by next spring, Tesla should be turning out 30 Roadsters a week.

Analysts wonder if the small startups have the wherewithal to move beyond building prototypes to producing a large number of vehicles. "There's this mindset in Detroit that these Silicon Valley guys don't know how to build cars," says Paul Wilbur, a former Chrysler executive who recently took over the CEO position at Aptera Motors, an electric vehicle manufacturer in Carlsbad, Calif. "For the most part, there's some truth to that."

Aptera, which makes an electric, two-seat, three-wheel model, said last year it would ship 4,000 of its cars by November 2008, ramping up to 10,000 in 2009. Instead, the company ran into design problems. Its first prototype featured an aerodynamic, composite body with a drag one-third that of an average car. "But the windows were stationary - Aptera couldn't figure out how to package roll-up, roll-down windows in the doors, which is really a simple design change," Wilbur says. "While the original design might have been more aerodynamic, we would have made the entire fast-food industry obsolete if we didn't put in windows that went up and down."

To make its cars more appealing - and useful - to the masses, Aptera hired a team of Detroit veterans, headed by Wilbur, who also will help the company build to economies of scale. "We're looking for a 50/50 balance of Detroit automotive engineering and California tech-industry [expertise]," Wilbur says.

By the end of next year, Aptera hopes to ship cars to the 3,600 customers who have already paid a $500 deposit (the cars will sell for around $30,000). In 2010, Aptera intends to ramp up production to about 45,000 vehicles, while its founder and current CTO, Steve Fambro, develops the company's first hybrid. Says Wilbur: "Aptera's not a single-model company."

Several upstarts are putting their all-electric models on the back burner to focus on hybrid motors, which were first widely introduced by the Toyota (TM) Prius.

Azure Dynamics, based in Oak Park, Mich., has a partnership with Ford to equip delivery truck chassis with its hybrid motors. So far Azure has received 146 orders for its hybrid powertrains, which includes supplying trucks for the U.S. Post Office and Con Edison, a utility company in New York City. "Right out of the gate, clients see about a 40% better fuel economy and reduced carbon emissions of 30%," says Michael Elwood, vice president of marketing for Azure. "But it's been really hard to get people's heads around what we're doing, even though environmentally it's the right thing to do."

One thing that players in the electric vehicle market agree on: The buzz surrounding GM's projected 2010 launch of its Chevrolet Volt - a $30,000 electric hybrid commuter car that will travel 40 miles on a single charge - is a good thing for the entire market. "While I don't see the Volt as necessarily being competitive with our product, I hope Chevy succeeds," says Elon Musk of Tesla. "One of the reasons why I have put so much effort into this is that I believe that the future of cars is electric."

But at this point, car industry analysts say that with electric cars starting at around $30,000 and as gas prices continue to drop, most Americans aren't willing to fork over the extra money, even if they get that the energy-efficient vehicles would help alleviate the effects of global warming.

"The question is, will the technology work, and can it be moved into a set of cars that are much more moderately priced to give consumers a viable option buying something other than an internal combustible engine?" asks GfK's Scott. "Right now, the basic technology and infrastructure isn't there. However, if we get back to $140 barrels of oil and the politics of this situation get to the point where the American government says we need to switch to the power grid, an electric vehicle car becomes much more of a reality." ![]()

Full package: Next Little Thing 2009

Where are they now? See how out past Next Little Things have done.

GM's long road back to electric cars

Will the Chevy Volt save the world?

GM: Death of an American dream

What's really killing Detroit

-

The Cheesecake Factory created smaller portions to survive the downturn. Play

-

A breeder of award-winning marijuana seeds is following the money and heading to the U.S. More

-

Most small businesses die within five years, but Amish businesses have a survival rate north of 90%. More

-

The 10 most popular franchise brands over the past decade -- and their failure rates. More

-

These firms are the last left in America making iconic products now in their twilight. More