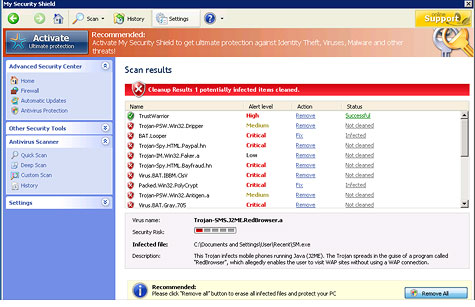

It may look legitimate, but this is a fake antivirus program designed to scam you.

This is part two in a week-long series on the ecosystem of cybercrime.

NEW YORK (CNNMoney) -- For decades, Internet scams have been as numerous as they've been easy to spot -- but fraudsters' tools and tricks are now becoming more sophisticated.

Those poorly written spam e-mails often seem more annoying than threatening, but they can wreak financial havoc on their victims. Precise statistics are hard to pin down, but experts believe global Internet fraud scams people out of hundreds of millions to billions of dollars each year.

Internet fraudsters have traditionally preyed on the vulnerable, including older victims who aren't as well-versed in computer technology. But scammers' skills at deception have improved so greatly over the years that even seasoned Internet users often have to do a double-take before they realize they've been duped.

For instance, a widely used, relatively new scheme that's difficult to detect features pop-up notifications that look just like antivirus software alerts. They usually say something to the effect of, "Your computer has been infected with 49 viruses, click OK to quarantine them."

Clicking OK sends the user to a website that claims their antivirus software license has expired, and a payment needs to be made before the virus problem can be mitigated.

These sites look completely legitimate -- and, adding to the scheme's plausibility, many of the spoofed websites even have working customer service phone numbers with "operators" on the other end of the line who will gladly take your money.

Another stealthily and fast-growing attack is called "spear phishing": sending e-mails to specific recipients from spoofed addresses that look completely legitimate. The attacks often appear to be from loved ones, claiming to be in an emergency situation and asking for money.

These schemes show that Internet scam artists, who had long been thought of as too unsophisticated to be considered real "hackers," are venturing into the realm of some of the more expert cybercriminals.

"Now, there isn't a very big gap in their capabilities," said Dave Aitel, president of security firm Immunity Inc. and a former computer scientist at the National Security Agency. "Re-shippers and check fraudsters are now just an arm of organized cybercrime."

Unlike their organized counterparts, online fraudsters tend to live below the poverty line and lack legitimate employment opportunities, according to Eric Fiterman, founder of security startup Rogue Networks and a former FBI cybersecurity special agent. Many steal to survive.

Even without the vast resources or technical skill of their more advanced criminal peers, Internet fraudsters are good enough at trickery to make their schemes successful.

"You could be a check fraudster with no technical skills, just social engineering skills," said Ajay Gupta, CEO of Gsecurity, an IT security contractor.

One common scheme asks people to deposit a check in their bank for a large sum and then wire most of that money to a recipient in a foreign country -- usually Nigeria.

"It sounds so obvious; alarm bells should be going off that this is a crime," Gupta said. "But the check that person receives look absolutely legit. Banks think it's real too."

Of course, check fraud and other scams are far from a new phenomenon. But the Internet has given fraudsters the platform they need to make their "business" profitable.

"Check fraud has been going on since we have had checks," said Bill Pennington, CEO of WhiteHat Security, a website security company. "What's new is that the Internet has taken down all geographical barriers. My grandmother did not have to worry about running into a Nigerian check fraudster at the grocery store."

The vast majority of people immediately identify these schemes as frauds, so fraudsters like to cast as wide a net as possible. Spam is one of the primary tools they use. The fraudsters often rent out botnets -- very large groups of compromised computers -- to send their messages to thousands, even millions, of recipients.

"They're casting wider and wider nets," said Angelo Comazzetto, product manager at IT security company Astaro Corp. "If they used to send 10,000 e-mails and get just a 1% response, now they'll send 10 million e-mails and get a 0.03% response."

Fraudsters don't just spam; they also prey on people using dating sites, job sites and classifieds.

For instance, AOL (AOL) autos, Craigslist or other online used car classifieds often host ads for cars at half their Kelley Blue Book value. If you inquire about the car, the seller will ask you to wire them a down payment before they ship you the car -- an irreversible transaction that siphons off money you'll never see again, never mind the car.

Just like in the offline world, Internet scam artists lure unsuspecting victims in by using very real-sounding, but fake charities, "make money from home" schemes, and deals. As you'd suspect, fraudsters don't have many scruples. Some recently took advantage of the California wildfires, for instance, setting up fake insurance websites aimed at victims.

Individuals aren't the only ones to be targeted by scam artists.

E-tailers face the threat of so-called "re-shippers," who buy merchandise with stolen or fake credit card numbers, or reverse their PayPal or credit-card payments after they've received the goods.

There are a few tip-offs of likely fraud -- mismatched billing and shipping addresses are a big red flag -- but few e-tailers have the resources to investigate every suspicious order.

"It's a sad call I have to make when someone pays with a stolen credit card, and I have to let the credit card's real owner know," said Michael Ellison, vice president of IT solutions retailer Virtual Graffiti. "It happens all the time."

When done well, the schemes can be very difficult to detect. Still, even with their improving skills, Internet scam artists don't come close to the capabilities -- or success rate -- of their counterparts in organized crime syndicates.

Coming Wednesday: The thriving underworld of organized cybercrime. ![]()