(MONEY Magazine) -- Our listless recovery has run into a series of obstacles lately -- a double dip in housing prices, dismal job growth, a downbeat consumer, and budget debacles on both sides of the Atlantic.

Yes, the debt-ceiling debate in Washington is over, allowing the U.S. to narrowly avoid becoming the world's biggest deadbeat. The deal, however, calls for the federal government to start making hundreds of billions in spending cuts at a time when Uncle Sam has been the only player in the economy willing to open up his wallet. And the compromise fell short of removing the threat that U.S. debt will be downgraded in light of Washington's long-term fiscal woes. In other words, there are yet more obstacles that must be overcome.

This would be a good time to recall an old saying in racing: "Focus on the road, not the wall."

That's what this story will help you do -- by tackling in sober-minded (as opposed to politically-spun) fashion the big questions about what's in store for the economy, and by offering guidance on how to steer your investments through these uncertain times.

Can MONEY guarantee you a winning ride? Of course not. Focusing on the wall, though, is rarely a good idea, no matter how bumpy the road is.

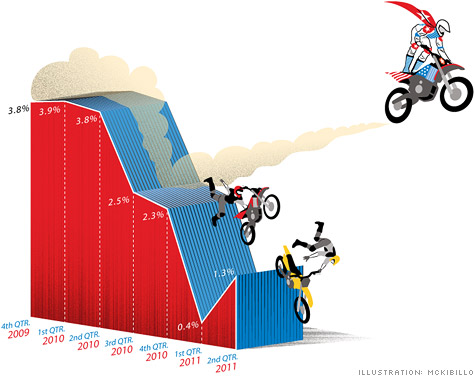

It's a growing possibility, but still not the likeliest scenario. The economy expanded at an anemic annual rate of 0.4% in the first quarter -- the slowest pace since the first half of 2009, when we were still in a recession. Second-quarter growth wasn't much better, as household spending actually declined in June.

Economists, in fact, are scrambling to ratchet down 2011 forecasts in light of a spate of disappointing economic news. The brokerage firm Janney Montgomery Scott, for instance, thinks our gross domestic product will now grow at an annual rate of 1.8% in the third quarter and 3% in the fourth, bringing total 2011 growth to around 1.6%, according to Guy LeBas, Janney's chief fixed-income strategist.

That pales in comparison to earlier consensus forecasts for 2.5% growth. And it's a frustratingly slow escalation after a major recession. Two years after the 1981-82 downturn, the economy surged more than 7%. And at this point in the 1975 rebound, GDP was growing 5%.

Still, there are signs that consumers, who account for two-thirds of all U.S. economic activity, began to ease their foot off the brake in July, and credit has expanded modestly for eight straight months. That's about as much as can be expected as households struggle to repair their balance sheets.

The savings rate has shot up from virtually nil before the financial crisis to more than 5% of disposable income. In the long run, that's good. In the present, however, "the economy will be soft for a lengthy period," says Martin Murenbeeld, chief economist for the asset management firm DundeeWealth.

Remember this: If major credit-rating agencies strip the U.S. of its AAA rating, higher borrowing costs across the economy will likely follow, which could further weigh on the consumer.

Economists think that government spending cuts required by the debt-ceiling deal could shave 0.2 percentage points off growth in 2012 and up to half a point in 2013, which means the economy would expand slightly more than 2% annually in the coming years. That's half the rate economists would like to see for real progress to be made on the jobs front.

What to do: That the economy will remain in low gear isn't reason to upend your long-term asset-allocation strategy. If all the economic and political uncertainty is making you feel like you must make a defensive move, however, rebalance your portfolio to reduce your equity exposure slightly.

Despite the rockiness in the markets of late, the Dow Jones industrial average is up 15% over the past year, while bonds are up around 5%. If you didn't rebalance at the start of the year, you could shift 10 percentage points of your equity allocation to a diversified mix of corporate bonds and cash. Not enough to let you sleep at night? Cut your stock allocation by an additional five to 10 points or so. Doing so may make you less likely to do something drastic that you'll later regret if we enter another period of big market swings.

Alternatively, favor stocks that tend to thrive in the later stages of an economic expansion, says Richard Weiss, head of asset allocation for American Century Investments. This means buying companies in the industrial and energy sectors.

Why? Historically, business cycles take nearly four years to unfold. In the early stages of a rebound, nervous consumers and businesses tend to spend on smaller-ticket items while delaying purchases of big, durable goods. Once that spending starts to recover in the latter half of an expansion, manufacturing gets going. And as factories expand, energy suppliers benefit. Granted, this isn't your run-of-the-mill recovery, but that affects the length and strength of the cycle, not its progression.

One company that holds a leadership position in both manufacturing and energy is General Electric (GE, Fortune 500), says Morningstar analyst Daniel Holland. Plus, its energy equipment business generates most of its revenue overseas, where growth is still robust. The company's earnings are expected to increase 19% annually over the next three years, yet it trades at a price/earnings ratio of just 10 based on estimated 2012 profits.

Fund investors have plenty of options. An exchange-traded fund such as iShares Dow Jones U.S. Industrial (IYJ) focuses on the largest names in the sector. Among energy ETFs, Vanguard Energy (VDE) gives you diversification in oil, natural gas, coal and energy services.

For the next two years or so, it'll remain pretty lousy. Take the June jobs report, which showed the economy added a mere 18,000 positions for the month. The July report was an improvement, showing 117,000 new jobs, but there's a chicken-and-egg problem, says Eric Stein, fixed-income portfolio manager for Eaton Vance.

Firms won't hire until they're certain of a sustainable increase in demand. Unfortunately, with one in six workers idled or underemployed, and many of the rest working to shore up their finances, shoppers aren't going wild at the malls.

Still, the hiring picture isn't all bleak. The economy averaged nearly 150,000 new jobs a month this year before June. That's not a robust rebound -- strong recoveries generate more than 200,000 -- but it beats the 80,000 monthly growth rate in 2010.

Bob Doll, chief equity strategist at the money manager BlackRock, thinks modest job growth will return after the impact of "temporary factors" that weighed down hiring begins to ease. Among them: the tsunami and nuclear disaster in Japan, oil prices that peaked at over $100 a barrel, and the floods and tornadoes that disrupted manufacturing in the South and Midwest.

Remember this: Even if hiring picks up, don't expect a return to happy days. Wages have grown 1.9% over the past year, while consumer prices have risen 3.6%.

What to do: So-called consumer discretionary companies -- retailers, automakers, and other businesses that sell things you can defer purchasing -- were among the best stock market performers earlier this year. But this group has surged only in months when the economy produced more than 200,000 jobs.

That's wishful thinking going forward, so shift into companies that sell what you need (think toothpaste and soap) no matter how bad the economy gets, says Kate Warne, an investment strategist for Edward Jones.

The iShares S&P Global Consumer Staples Sector Index Fund (KXI) has the added benefit of investing in large companies that sell globally. The fund's biggest stakes are in Nestlé (maker of Taster's Choice coffee and Lean Cuisine frozen meals) and Procter & Gamble (Pampers diapers and Duracell batteries).

There's the real rub. If corporations, which are sitting on nearly $2 trillion in cash, aren't willing to use their war chests to hire, there's little that the government can do to coax them. And Uncle Sam has pretty much run out of tools to jump-start the economy on its own, says Joseph Davis, chief economist for Vanguard.

Under normal circumstances, to fight a downturn the Federal Reserve lowers borrowing costs, thus spurring consumer spending, which in turn leads businesses to hire more workers. Short-term interest rates have been near zero since early in the Great Recession. As for public sector spending, thanks to austerity measures by municipalities, states, and the feds -- as well as European nations -- government has become the anti-stimulus lately. Even once-red-hot emerging-market countries are growing slower as many central banks have been hiking interest rates to cool inflation.

Remember this: Earlier this year, conventional wisdom said the Fed would start lifting interest rates by the fourth quarter. Now Bernanke & Co. are expected to be on hold until late 2012 or 2013, according to a Bank of America Merrill Lynch survey of money managers.

That should help stave off a recession. "When interest rates are kept near zero and are kept below the inflation rate, it's very hard to experience a contraction in economic activity," says David Kotok, chief investment officer at Cumberland Advisors.

What to do: A combination of low rates and sluggish growth puts an emphasis on defensive investments that produce decent income. Merrill Lynch strategist Michael Hartnett notes that until the Fed begins to hike rates, the bull market in corporate bonds should continue. True, even investment-grade corporate bonds aren't as safe from a credit stand-point as Uncle Sam's debt (though the debt-ceiling debacle calls into question how safe Treasuries are).

Still, among consumers, governments, and corporations, businesses are furthest along in having reduced their debt and boosted savings. As a result, bonds issued by financially healthy companies are likely to be in demand in a low-rate, slow-growth world.

Among corporate bond funds, Harbor Bond (HABDX), which is in the MONEY 70 list of recommended funds and ETFs, has beaten most of its peers over the past three, five, 10, and 15 years. It's also a cheaper way to buy the services of Pimco bond guru Bill Gross than his flagship Pimco Total Return.

It's likely to be less of a concern going forward, now that the economy is growing slowly and wages aren't rising in real terms. There are other forces that will push inflation higher, however, including rising commodity prices stemming from robust demand for food, energy, and construction materials in fast growing Asia and Latin America.

The Leuthold Group tracks a basket of about 70 commodities. Currently, 89% of them are selling at higher prices than they were a year ago. There have been three other times when that figure approached 90%: in the mid-1970s, the late 1970s, and 2004-05, says Doug Ramsey, director of research at Leuthold. In the first two instances, inflation hit double digits, and in 2005 the consumer price index jumped nearly 4%.

Jason Hsu, chief investment officer for Research Affiliates, thinks the combination of higher commodity prices and the continuing supply of cheap money by the Fed means consumer prices, which have risen 3.6% over the past year, could go up at a 4% clip in the next several months and possibly 5% in the next several years.

Remember this: A return to the 1970s isn't in the cards, but if inflation hits that 4% mark, your stock and bond portfolios could take a hit.

What to do: Lean toward defensive stocks that don't grow particularly fast (so expectations are low to begin with) but that pay sufficient dividends to let you keep pace with inflation. Adam Parker, chief U.S. equity strategist for Morgan Stanley, favors health care and utilities, neither of which requires a strong economy to thrive.

Parker recently added Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMY, Fortune 500) to his recommended list. The drugmaker, like its peers, faces major patent expirations next year. But Bristol-Myers has sold off ancillary businesses to raise cash to make acquisitions or buy new drugs. Plus, the stock yields 4.7%, more than double the average yield for the sector.

As for utilities, Franklin Utilities A (FKUTX) (4.25% load) is a fund that breaks from some of its peers by sticking mostly with regulated electric and gas utilities, rather than straying into telecom and energy. Plus, it delivers a decent yield of 3.5% vs. the category average of 3.2%.

Not necessarily. Western Europe's economy is moving even more slowly than ours, and its debt problems are worse. Governments are cutting spending, and the European Central Bank has been raising interest rates. That leads James Paulsen, chief investment strategist for Wells Capital Management, to wonder: "How are they going to grow?"

In Asia, Eastern Europe, and Latin America, by contrast, GDP growth over the next three to five years is projected to rise three times faster than in the developed world, according to Pimco.

"In the emerging markets, the risk is overheating," says Alexi Savov, a professor at New York University's Stern School of Business. In China, for example, Beijing's efforts to tap the brakes on the economy to stem inflation could lead to an abrupt slowdown, says Jeremy DeGroot, chief investment officer for Litman/Gregory. The chance of a "hard landing" would grow if China's real estate bubble keeps expanding and then bursts, he says.

Remember this: Economic growth and stock prices don't move in sync. If they did, Chinese stocks would be up 10% for the year, not down 2%, and U.S. equities would be flat.

What to do: There's a good chance you don't need to do anything when it comes to the emerging markets. Given the popularity of these stocks in recent years -- and their outperformance over the past decade -- you may already have a quarter or more of your foreign stock portfolio in emerging-market shares. That's plenty.

Got a lot less? You can use this year's pullback in China and other emerging markets to add to your position, says Jason Pride, director of investment strategy for the money management firm Glenmede.

A simple way to do that is through a broadly diversified fund such as T. Rowe Price Emerging Markets Stock (PRMSX) or Vanguard Emerging Markets. (VWO) Both are in the MONEY 70.

As for Europe, Cumberland's Kotok notes that despite all the bad press about Greece, Italy, and Portugal, Northern European economies, such as Germany's and Sweden's are quite healthy.

So if you're worried about debt contagion abroad, you can sell, say, 10% to 15% of your stake in a typical big international fund -- which will tend to hold about two-thirds of its assets in Western European companies -- and focus instead on single markets that are on much stronger financial footing. iShares MSCI Germany (EWG) has returned 17% over the past year, vs. 11.4% for the MSCI EAFE index, the benchmark for most international funds.

Yet German stocks, which have historically traded at a 24% premium to stocks in the EAFE index, now trade at a 10% discount since profits are growing faster among German companies than they are in other parts of Europe or Japan. If the global economy takes a turn for the worse, German stocks could fall in lockstep with the rest of the world. Managing your portfolio based entirely on worst-case scenarios, though, won't keep you on the road to your goals. ![]()

Carlos Rodriguez is trying to rid himself of $15,000 in credit card debt, while paying his mortgage and saving for his son's college education.

| Overnight Avg Rate | Latest | Change | Last Week |

|---|---|---|---|

| 30 yr fixed | 3.80% | 3.88% | |

| 15 yr fixed | 3.20% | 3.23% | |

| 5/1 ARM | 3.84% | 3.88% | |

| 30 yr refi | 3.82% | 3.93% | |

| 15 yr refi | 3.20% | 3.23% |

Today's featured rates: