Search News

(MONEY Magazine) -- After three years of belt-tightening, Tom Van De Water, 41, a customer information systems manager in Stratham, N.H., has finally loosened the family budget. This year he and his wife, Alyson, 41, celebrated their 10th anniversary in St. Lucia, and she bought him a pricey watch for his birthday.

Are these signs of a return to the free-spending good old days, when the couple wouldn't have hesitated to buy the best stuff and top off one of their frequent dinners out with an expensive bottle of wine? Not by a long shot.

Today the couple, who have three children (ages 8, 7 and 18 months), carefully plan outings. "We treat each time as special," Van De Water says.

The family's SUV, a 2007 Honda Pilot, was purchased off a used-car lot, and their maple dining room set was a $900 bargain nabbed on Craigslist. "We're more thoughtful about how we spend," he says. "We're realigning our values."

So are a lot of people. Since 2008, the worst economic downturn since the Great Depression has dramatically changed the way millions of families manage their money and their lives. Some actions were predictable, like cutting up credit cards, clipping coupons, and suddenly remembering that, yes, you really do need to save for a rainy day. What you were living through, after all, was a downpour of financial troubles.

Now, more than three years after the collapse of financial institutions, stock prices, and home values combined to usher in a new age of austerity, enough time has passed to ask a critical question: Which of our new-found habits and values will really stick, lasting even after the economy rebounds -- and which won't?

The Great Recession officially ended in June 2009. The recovery has been anemic at best -- in fact, 80% of Americans believe the country is still in recession, according to a recent Gallup poll -- and the threat of a double dip hangs over us like a swollen storm cloud. That alone suggests that at least some of the behavioral shifts will stay in place for some time.

"Big periods of economic upheaval can define a generation," says Paul Flatters, managing partner of Trajectory Partnership, which monitors consumer behavior. "Not so much because of the depth of this recession, but because of its prolonged nature, it will have lasting impact."

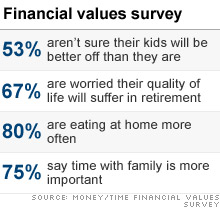

To help define the new normal, MONEY and our sister publication Time collaborated on a pair of wide-ranging surveys in late summer to explore Americans' changing financial values.

The polls were a follow-up to surveys taken in the months immediately before and after the 2008 meltdown. In dozens of interviews, many families, like the Van De Waters, reported that they were relenting on knee-jerk resolutions made at the height of the crisis.

After all, never ever eating out again is probably unrealistic, and there's a limit to how long you'll shop only sales, watch free TV, and read at the library. Still, a great many folks are also doubling down on big behavioral shifts like quality time with family and saving more for retirement -- two areas where the readings today are even higher than they were at the deepest point of the pullback.

In the MONEY poll, one in five said they were financially better off now than they were a year ago. That isn't exactly a landslide of prosperity. It is, however, twice the rate of those who felt that way in the 2008 survey.

Higher earners (households with an annual income of at least $75,000), not surprisingly, were even more likely to report improvement, and folks across the income spectrum have a higher degree of optimism about their personal finances in the coming 12 months than they did three years ago. Far more now have confidence they will hang on to their house, and fewer worry that they'll be forced to accept a pay cut.

None of this is to minimize lingering pain. Median household earnings have fallen three years in a row, according to the Census Bureau, and the poverty rate is the highest it's been in nearly 20 years.

In the Time poll, 83% feel Americans have less economic security than they did 10 years ago; more worry about whether they'd be able to find work if they lost their job; and greater numbers report dipping into college or retirement savings to make ends meet than was the case three years ago.

Collective optimism has also been dinged. People who live through an economic shock have far less confidence in government for most of their life, according to a National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) study.

The MONEY survey confirms this skepticism: Only 34% were optimistic about the President's ability to restore growth, and 17% were optimistic about Congress. True, the survey was conducted shortly after the August debt ceiling battle, when many were especially fed up with government. Still, people overall are clearly more pessimistic about the economy now than three years ago --even as they are starting to feel better about their own finances.

This split between cautious personal optimism and deep concern for the country is one of many profound shifts in financial attitudes over the past three years revealed in the MONEY and Time surveys.

Here are other key findings that shed light on where Americans stand now and where they think they're headed when it comes to managing their money.

Thrift is in vogue

Over the past three years, a taste for designer labels -- so 2007 -- has morphed into a penchant for spotting deals. And living within your means has become cool again. Or at least you've noticed your friends and neighbors have swung around to your way of thinking. The new appreciation for bargains and budgets born during the 2008 financial crisis appears to have become even deeper in 2011.

In the MONEY survey, nearly half the respondents said they felt guilty when they purchased a luxury product, and 85% spend more time looking for deals before they buy -- higher readings than in the earlier poll. And 83% were convinced they would remain frugal in the future.

Two in three said their financial priorities have changed as well. How? Lots of folks are building an emergency fund (57%), putting less focus on material things (64%), and eating at home more often (80%). That attitude adjustment has put a big crimp in consumer spending, which has been flat for the past three years, according to the Bureau of Economic Analysis. "People now think two, three, four times before they spend," says Flatters. "Marketers have to convince them the purchase is not frivolous."

A preoccupation with value is likely to persist in part because the next set of consumers, young people, have felt the squeeze too. Dominant beliefs about how society and the economy work are formed from ages 18 to 25, the NBER study found. This age group has suffered the sharpest income drop -- median earnings of those ages 15 to 24 fell 9% last year -- and have been among the hardest hit by unemployment.

As if that wasn't searing enough, many young people experienced the trauma of watching their parents lose their jobs and homes, take pay cuts or suffer big drops in home values and retirement accounts.

These kinds of setbacks leave emotional scars, says James Burroughs, associate professor at the McIntire School of Commerce. "Students saw their parents get wiped out after working so hard," he says. "To them, it all seems like a futile exercise."

So they are likely to place a lasting value on more moderate living with an emphasis on relationships and experiences. Says Burroughs: "They have a much greater awareness that money cannot buy happiness."

Family time trumps stuff

In the MONEY survey, 75% said spending time with family was more important than ever, up from 69% three years ago, suggesting many folks have tried it, liked it, and are determined to stick to it. And more than half said they'll continue to be more focused on relationships than material gain well into the future.

Holly Rasmussen, 42, a business consultant and divorced mother of two children in Parker, Colo., is one of them. To save money after she was forced to take a pay cut during the recession, she got rid of her landline and home fax, downgraded her cable package, and dumped the gym membership. Her most rewarding shift, she says, has been quitting the restaurant habit, which has helped her overhaul her relationship with her kids, ages 13 and 11.

"We have more time together because we're not sitting in a restaurant with people being ushered in and out," she says. "We're in our living room and it's just the three of us talking about our day. We know each other better." Rasmussen says the family now plan meals and cook together often. She figures her quality time with the kids has doubled.

She's also teaching them to be smart about money. Like the 58% in the MONEY poll who are asking their offspring to be more careful about what they spend, Rasmussen now puts the children on a budget when they go shopping, giving them a limited amount to spend as they see fit. She says, "Almost instantly they went from wanting the best of the best to, 'Hey, look at these five shirts I can get on the sale rack.'"

Investors are wary

Despite the market's volatility over the past three years, investors aren't abandoning stocks, and most don't expect big price drops in the near future.

That's particularly true among higher earners; just 16% of families earning $75,000 or more believe the market will be lower a year from now. Investors, however, aren't reverting to big bets on tech and other highfliers.

Instead they're hunkering down, looking for ways to minimize losses down the road. Half of affluent families have focused on diversifying their assets over the past three years, the MONEY survey found. A telling 43% said they were more concerned with capital preservation than gains, and nearly 30% said this shift is permanent.

That describes Richard Anklin's revamped strategy to a tee. Anklin, 64, and his wife, Sharon, 65, both retired, built a $1.3 million nest egg during 30-plus-year careers working at Ford by investing largely in stocks and sticking with them through the ups and downs of the market.

Though their investment mix was aggressive for their age, they stayed the course through the recent downturn --their stocks lost 40% after the 2008 crash -- expecting their portfolio to bounce back, as it had so many times before. But three years later, their holdings are still down sharply.

Worried by the duration of the downturn and their advancing years, the couple is now making major shifts in their portfolio. They're dialing back on stocks and have annuitized part of their savings to produce steady income -- smart moves since they're in retirement. As a result, though, their projected income from their investments has dropped by a third, and Richard is concerned about whether he and Sharon will be able to maintain their standard of living and help put four grandkids through college as he planned. "But I had to do it," Richard says. "I had to protect my principal."

Austerity has eased up

Debt played a big role in getting the country into this mess, and eliminating debt, on both a national and personal level, seems key to getting out of it.

Washington may be stuck on figuring out the first part, but families are bent on cleaning up their own balance sheets. The credit bureau TransUnion reports that credit card debt this year has fallen to a near decade-long low, averaging $4,700 per borrower.

In the MONEY poll, 62% said they are intent on paying down their credit cards -- a far greater number than in the 2009 survey. "People are putting their heads down and systematically paying off debt in ways I've not seen in 30 years," says Mark Cole, chief operating officer of CredAbility, a nonprofit credit counseling agency.

Lately, though, there has been some backtracking. Even as they're paying off cards, people seem more willing to use them: In the MONEY survey, only 43% say they no longer carry a balance, down from 63% three years ago.

Just-released Federal Reserve data also show a spike in charging by consumers during the second quarter, although credit card debt overall remains sharply lower than 2008's record levels. Saving rates show a similar pattern: Currently 5%, they're down from a post-crisis peak of 7.1% in May 2009 but still way better than the near-zero rate of pre-recession days.

What's going on? Some experts believe consumers are finally finding a sustainable middle ground. After all, it's tough to live like a monk forever.

Case in point: Karen Dhanie, 38, whose family cut way back on everything from groceries to vacations after she was laid off in 2009 from her job in regional sales with Citigroup. Now working for Home Depot in Orlando, Dhanie says she and her husband, Harry, 43, a manager at a national pharmacy chain, got fed up with a lesser cellphone plan and upgraded. She no longer drives out of her way to get a better price on everyday purchases. But, she says, "we still are very conscious about what we buy. We're not splurging like before. Our vacations are less luxurious. We plan ahead."

Why new habits will last

Cole thinks families like the Dhanies will stick with the program. Consumer willingness to spend and borrow, he says, is a function of job security and confidence in the economy, both abysmally low now and likely to stay low for a long while.

He says shedding debt is like quitting cigarettes. Once you kick the habit, you get religion and strive not only to avoid future debt but also to pass this wisdom on to your kids.

Robert Kaplan, a professor at the Harvard Business School, agrees, noting a rare double whammy: Both government and consumers are pulling in their horns. "This creates enormous economic headwinds," he says.

Not everyone sees all the changes as lasting. Scott Hoyt, an economist at Moody's Analytics who has studied the recession's effect on consumers, believes people generally will continue to save more and borrow less, but that they'll start spending again once the economy get stronger. "Consumers make these changes cyclically," he says. He notes that restaurant spending perked up as the economy improved last year, only to fall off a cliff again when things got dicey this summer.

What's clear: The longer tough conditions continue, the more folks accept it as normal, which in turn serves to cement their new values. "There's a huge shift of people who now say this is the way it's going to be forever -- or at least a long, long time," says Carl Van Horn, a professor of public policy at Rutgers.

Tali Yahalom contributed to this article.

Read the next part of this story: Timely moves for changing financial values ![]()

Carlos Rodriguez is trying to rid himself of $15,000 in credit card debt, while paying his mortgage and saving for his son's college education.

| Overnight Avg Rate | Latest | Change | Last Week |

|---|---|---|---|

| 30 yr fixed | 3.80% | 3.88% | |

| 15 yr fixed | 3.20% | 3.23% | |

| 5/1 ARM | 3.84% | 3.88% | |

| 30 yr refi | 3.82% | 3.93% | |

| 15 yr refi | 3.20% | 3.23% |

Today's featured rates: