Two years ago the Bank of New York Mellon CEO almost left to run Bank of America, but he changed his mind and the board welcomed him back. That's when the trouble started.

FORTUNE -- When Robert Kelly walked into the White House that Monday morning, he had every reason to be on edge. It was Dec. 14, 2009, and the CEO of Bank of New York Mellon was one of an elite group of bankers who had been summoned by President Obama. At the time, Kelly was deep in negotiations to leave his post at BNY Mellon, the eighth-biggest U.S. bank by assets, and take the top job at the industry's largest institution, Bank of America. The previous Tuesday he'd told the BNY Mellon board at a breakfast in Boston that "Bank of America wants me for the job," and that he planned to take it.

The 11 a.m. meeting with the President was held in the windowless Roosevelt Room, just steps from the Oval Office. Kelly and fellow CEOs including John Stumpf of Wells Fargo (WFC, Fortune 500) and Jamie Dimon of J.P. Morgan Chase (JPM, Fortune 500) found seats at the table next to officials such as White House economic adviser Christina Romer and Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner. When the meeting came to order, President Obama delivered a stern message. He urged the bankers to revive lending to small businesses and lectured them about Wall Street pay. The federal government, the President stressed, had rescued the banks during the financial crisis, and it was beyond any notion of common sense -- a virtual insult, in fact -- for their top brass to pocket gigantic pay packages after the American taxpayer had bailed them out.

Ironically, Kelly had for days been pushing for precisely the kind of exorbitant pay from Bank of America (BAC, Fortune 500) that President Obama was condemning. The week before, BofA had fully repaid its $45 billion from the Troubled Asset Relief Program, officially freeing itself from TARP's draconian restrictions on compensation. Over the next three days the BofA search committee hammered out a draft contract with Kelly that included an upfront payment of more than $20 million and guaranteed another $15 million to $20 million a year. The committee even agreed to Kelly's demand that BofA move its headquarters from Charlotte to New York City, where Kelly owns a sumptuous townhouse.

But over the weekend the BofA directors had begun fretting about what they should have foreseen before offering Kelly such a sweet deal: a populist uproar on Capitol Hill the instant the news broke. If Kelly needed more evidence that his dream package was endangered, the President's harsh words in the Roosevelt Room that Monday seemed to seal its fate. He must have realized that his chances of securing perhaps the biggest job in banking were fading fast.

Incredibly, Kelly still had a few hours to save his highly lucrative CEO post at BNY Mellon (BNY) -- even though this wasn't the first but the second time in just two months he'd flirted with BofA. The BNY Mellon board had scheduled a meeting at 4 p.m. to announce Kelly's departure and had the press release ready to go. So Kelly raced back from the White House to New York to save his job. He called lead director Wesley von Schack from Reagan National Airport and declared, "I want to stay." Around 5 p.m. he arrived in a conference room at BNY's headquarters at 1 Wall St., where von Schack was talking to the other directors on speakerphone. Von Schack, a retired CEO of utility Energy East, invited Kelly to speak. The CEO was now practically begging for his job from the same directors he'd brushed off a week before. "I don't like the way BofA has handled this process," he explained. "I wouldn't have a good working relationship with the directors." He apologized for his actions and added, "This is where I want to be."

The BNY Mellon directors spent some time deliberating -- and took Kelly back. It was a fateful and misguided decision. In retrospect, it would have been far better if the board had forced him to go ahead with his resignation that afternoon. Because from that point on, the relationship with his lieutenants, the directors, and especially von Schack was poisoned. The surreal events of that day marked the start of a downward spiral of distrust at BNY Mellon that less than two years later would end in Kelly's forced resignation -- this time for real -- on Aug. 31 of this year. The press release that day contained a single-sentence explanation for Kelly's exit: "Robert P. Kelly has stepped down due to differences in approach to managing the company."

Kelly's departure -- the sudden, shocking resignation of a star CEO -- has received remarkably little attention or explanation. Today BNY Mellon stands in the spotlight primarily as the target of two major legal battles. First, the U.S. Department of Justice and a handful of state attorneys general are seeking more than $2 billion in damages from BNY, charging that the bank cheated customers in foreign-exchange transactions -- alleged practices that long predate Kelly. (For more on those charges, see box) Second, BNY, serving as trustee, endorsed an $8.5 billion agreement between BofA and investors that bought BofA's toxic mortgages -- and now it's being sued by the New York attorney general's office, saying that BNY failed in its duty as trustee of the mortgage-backed securities.

But now, for the first time, the full story of Kelly's fall from grace can be told. Fortune assembled the dramatic narrative from interviews with dozens of sources, almost none of whom spoke for attribution but whose accounts could be confirmed by others. The tale chronicles a total mismatch between the personality and skills of a CEO and the challenges, and culture, of the company he was running. Robert Kelly, 57, can be a charming leader, with a sophisticated financial mind. His history shows that he's always looking for the next new thing -- a grander job, more money, and more excitement. Kelly, who declined to be interviewed for this story, is a big-picture thinker with an artistic, creative temperament who relishes business as an adventure. His weakness is a surfeit of self-confidence bordering on hubris.

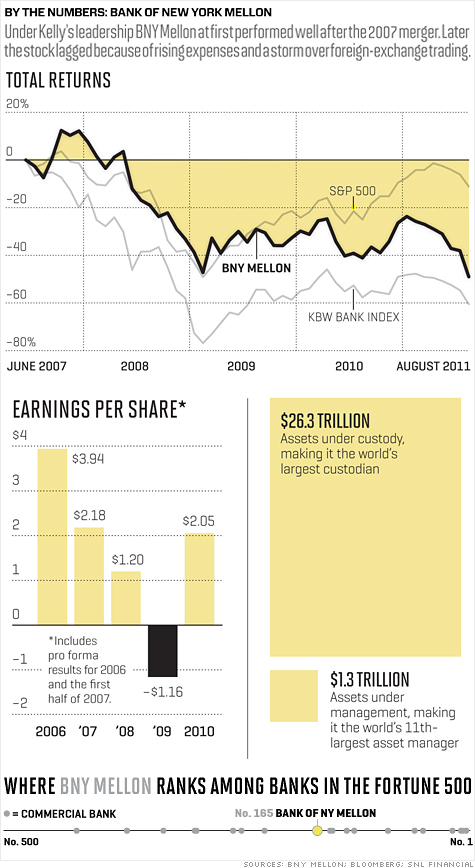

BNY Mellon couldn't have been a worse fit for Kelly. With $14.9 billion in 2010 revenue, BNY Mellon rankedNo. 165 in this year's Fortune 500 -- the 12th-largest commercial bank on the list. But it's a highly conservative, old-line institution that specializes in mundane, grind-it-out businesses and prizes tradition, self-effacement, and loyalty. It is a major player in asset management. But its signature franchise, where it ranks No. 1 globally, is asset servicing -- the business of performing record keeping, securities lending, and back-office tasks for investment funds and financial institutions. That's anything but glamorous, and it's not Bob Kelly.

The story of Bob Kelly's downfall isn't primarily about BNY's financial performance, which was middling but hardly disastrous. It's chiefly a classic study in a dysfunctional relationship between a boss and a board. Even after pleading to keep his job, he bristled at taking orders from the directors who took him back. He kept going his own way, making decision after decision without consulting the board -- everything from exploring options for a new headquarters to a surprise plan to shrink the workforce. And veteran directors never got over what they viewed as an act of disloyalty that fateful week in December.

"Genteel was not Bob's style"

A Canadian by birth, Robert Kelly grew up in the scenic Atlantic port city of Halifax in Nova Scotia, where his father worked as a tax accountant. Canadians like to compare Nova Scotia to America's Midwest: Both have a culture that encourages affability and plainspokenness -- qualities that his friends say Kelly shares, notably an unadorned bluntness. After graduating from Saint Mary's University in Halifax with a degree in accounting, Kelly joined KPMG and quickly discovered a way to win new clients. In 1979 he bought one of the first desktop computers, the Radio Shack TRS-80. He learned to program the machine and showed small businesses how to reap major savings by keeping their books electronically.

In 1981, Kelly joined Toronto-Dominion Bank (TD) in its information technology department. Moving to London soon after, Kelly wrote pioneering programs that quickly valued the interest rate and currency derivatives that were just gaining favor in Europe, giving TD's traders an edge that brought big profits. He became CFO in 1992 at age 36. "Bob was highly analytical, a great salesman, and he even made business fun," recalls Stephen McDonald, a former colleague at TD and now co-CEO of investment bank Scotia Capital. "It was clear he was a top candidate to be CEO and wanted the job." But Kelly lost his opportunity when TD acquired Canada Trust Financial and named its CEO, W. Edmund Clark, as heir apparent.

In 2000, Kelly joined First Union in Charlotte -- soon to be renamed Wachovia -- as CFO. First Union was undergoing a painful restructuring following years of whirlwind expansion that had turned reckless with the disastrous acquisitions of CoreStates and the Money Store in the Northeast. Kelly brought a relentless, disciplined approach to measuring which businesses and acquisitions provided the best returns, and ensuring that the bank allocated its capital to those areas. During his tenure as CFO from 2000 to early 2006, Wachovia delivered shareholders a total return of 92%, handily beating both the bank index and the S&P 500 (SPX). For two straight years, 2004 and 2005, the analysts polled by Institutional Investor voted Bob Kelly the best CFO of a large bank in America.

One of the great mysteries of the Kelly saga is that a leader so well liked at Wachovia would rouse so much ill-feeling from his co-workers and his board just a few years later at BNY Mellon. But in retrospect, it's also remarkable that at Wachovia, Kelly fared so well in a courtly culture at odds with his own curt style. "It was a civil, Southern place, and that wasn't Bob," recalls Thomas Wurtz, who served as treasurer under Kelly. "Bob was honest and direct." Kelly sparred frequently with CEO Ken Thompson, who wanted to make Wachovia a big player in capital markets, a business Kelly disliked. "I don't see it that way," he'd tell his superiors in meetings, showing resistance practically unheard-of at the bank. "Genteel was not Bob's style," says Gregory Thompson, a former financial executive at Wachovia. "He wouldn't be offensive, but he'd dig his heels in."

Kelly's co-workers at Wachovia found him a down-to-earth, fascinating colleague with a zany side. "Bob had this boisterous laugh you could hear across the floor," recalls former general counsel Mark Treanor. His colleagues still marvel over his mathematical abstract drawings. Often in meetings he'd do pen-and-ink caricatures of the folks in the room on a big pad while they discussed loan reserves or foreign-exchange hedging, then get smiles when he showed them their "likenesses."

One year Kelly held a Christmas party at his home with a professional caricaturist on hand to draw the guests. At the evening's end, Kelly turned the easel around and made a quick sketch of the caricaturist that at least equaled the expert's work. "The doodling seemed to give him a freedom of thought, so that his brain could roam freely, so that he was unbounded by pure logic," says Gregory Thompson, who describes Kelly as a "3-D thinker." A history buff, Kelly festooned his office with photos of Winston Churchill and Orville Wright, as well as a seventh edition of Adam Smith's The Wealth of Nations from 1800, purchased on eBay.

Kelly craved the limelight. He adored, for example, giving witty speeches explaining Wachovia's strategy to employees at call centers. But according to Wachovia veterans, Kelly also wanted to be the public face of Wachovia and chafed that Ken Thompson, not Bob Kelly, played the main part in telling the Wachovia story to Wall Street. A friend of Kelly's, who considers him a terrific banker, explains why Kelly can be either enthralling or irksome, depending on the audience. "Bob is used to being the smartest guy in the room," he says. "He presents his ideas like they're amazing. The people wowed by him love it. They feel lucky to be throwing ideas around with a guy that smart." But for those "not wowed by his ideas" or who have a different view, says the friend, he comes across as off-putting, arrogant, and sometimes rude.

Because he was around the same age as Thompson, Kelly's prospects of ever becoming CEO of Wachovia looked dim. But he had suitors. In 2006 the board of Mellon Financial decided that Kelly was just the change agent it needed to revive the fabled institution, then under extreme pressure from activist hedge funds. And Kelly's biggest champion on the Mellon board was a flinty retired utility executive -- none other than Wesley von Schack. Kelly was announced as CEO of Mellon in February 2006.

It didn't take Kelly long to make a transformative move. In early December, after just 10 months at Mellon, Kelly announced a major deal -- a merger with Bank of New York. To Kelly the union made great business sense. BNY was powerful in asset servicing but underweight in asset management. For Mellon the mix was the reverse: It boasted a major investment franchise and a puny presence in custody. A few BNY directors worried that in their interviews with Kelly he was in the "all about me" mode, incessantly talking about his accomplishments. Still, the two boards determined that BNY's chief, Thomas Renyi, would remain as chairman but step down as CEO. Kelly would take charge, running a business three times the size of the former Mellon.

Kelly the performer didn't hesitate to sketch a fantastic picture of the union. On Dec. 4, 2006, in a webcast to analysts, Kelly predicted that the combined BNY Mellon would begin by posting $2.5 billion in after-tax earnings, and grow rapidly from there. But the bank wouldn't come close to delivering on those promises. (It took until 2010 to reach the $2.5 billion profit goal.) A big reason for that, of course, was that the bottom dropped out of the economy not long after the merger. But eventually the board came to perceive Kelly as lacking sufficient desire to cultivate clients or the will to control escalating costs.

At the outset, though, the two companies appeared to meld extremely well. They boasted two of the longest, proudest histories in the annals of American business. Bank of New York was the oldest financial institution in America, founded by Alexander Hamilton in 1784. Family patriarch Thomas Mellon had launched his bank in 1869. A key difference: Bank of New York was renowned for frugality, bordering on outright cheapness. In the 1990s dozens of analysts would stand in line waiting to use a handful of Bloomberg terminals. Managers would sometimes forgo raises and bonuses for as long as two years if costs got too high.

The two boards merged smoothly. For the most part, the directors were CEOs or retired CEOs of medium-sized to fairly big companies, often from the Midwest, and they shared a "you work for us" attitude toward management. (Notably, one current director and Mellon board holdover is John Surma, CEO of U.S. Steel, who, as a trustee of Penn State, this November was the person who announced that legendary football coach Joe Paterno had been fired.) "The board bonded quickly," says Frank Biondi, a former chairman of Viacom (VIA) who left the board in 2008. "It didn't have high-profile people, but it was a smart, capable group." The directors assisted Kelly by creating an integration task force, reporting directly to the board, which over time created $1 billion in cost savings by closing offices, reducing staff, and merging systems.

Kelly had barely settled in to his new office in New York when he faced his first major test. The financial crisis struck in mid-2008, pounding asset-management fees as bond and stock prices plummeted. To the board, Kelly's leadership through the crisis looked sound. BNY took far smaller losses than most other banks and paid back its TARP money earlier. By late 2009 the stock had rebounded to $30 from a low of $19. Kelly was playing a major role in several industry groups, including the prestigious Financial Services Roundtable, and was highly respected in Washington as a counselor to the administration on regulatory matters.

At the time, his public role appealed to the directors. Over breakfast the day of each board meeting, Kelly would keep the directors informed on what BNY could expect from regulatory reform in Washington. His role as ambassador was also good business: BNY Mellon won the exclusive contract from the Treasury Department to handle all of the bookkeeping, accounting, and distressed-asset auctions for TARP.

In return the board gave its CEO the royal treatment. The compensation committee, headed by von Schack, modeled Kelly's compensation after that of highly paid CEOs of extremely large companies -- mostly a lot larger than BNY Mellon -- including J.P. Morgan, BlackRock (BLK, Fortune 500), Citigroup (C, Fortune 500), and Wells Fargo. From 2007 to 2010, Kelly earned, on average, $18 million a year, making him one of America's highest-paid CEOs, financial or otherwise. The directors believed Kelly was leading BNY to the big time.

Outside the office, Kelly enjoyed a lifestyle worthy of a Wall Street titan. In 2007 he paid $14.7 million for a five-story, 6,300-square-foot townhouse on Manhattan's Upper East Side, nine blocks from the stately former Mellon family mansion. The house was meticulously renovated in the Mackintosh architectural style, inspired by the British arts-and-crafts school. The library shelving was carved from a single walnut tree. A folk-art Canadian Mountie doll was placed in the parlor floor window, as if to stand guard.

Kelly's flirtation with BofA

The crack that would weaken, then destroy, the bonds of trust between Kelly and the board opened when Kelly began his on-again, off-again dance with Bank of America. In late October 2009, Kelly started negotiations with BofA -- without telling his board. From the start, any agreement faced a stiff obstacle: It would cost BofA well over $20 million to buy out Kelly's package of stock and retirement benefits at BNY Mellon. Kelly wanted a chance to run the nation's biggest bank, but he didn't want to give up his lucrative compensation to do so. BofA was still under the TARP rules, so the Treasury Department could veto a pay deal it considered excessive. Members of the compensation committee tried negotiating with Kenneth Feinberg, at the time the Obama administration's executive-compensation czar. But Feinberg adamantly opposed any large buyout, saying that it was totally inappropriate for a company taking government money, and it would never happen on his watch.

As it turned out, Feinberg's objections weren't the deal killer. On Nov. 3, Kelly, members of the search committee, and assorted lawyers and headhunters met at BofA headquarters in Charlotte and by phone until around 11 p.m. The next morning the exhausted participants were shocked to read a full account in the Wall Street Journal of how Robert Kelly was being recruited for the BofA post. Kelly and his team were furious, suspecting that insiders who wanted to see BofA executive Brian Moynihan get the job had leaked the story to the Journal. "They're forcing me to drop out!" Kelly complained. That day he wrote a memo to his executive committee addressing the BofA report: "I want to make clear: I am not interested."

In early December it appeared that Bank of America would repay TARP far sooner than expected. The BofA board wanted desperately to escape the program's pay restrictions so that the company could hire an outsider as CEO, the preference of the majority of the directors. Its six-person search committee began once again courting their favorite candidate: Bob Kelly. And Kelly was still more than willing to listen.

This time Kelly informed von Schack about the new negotiations as soon as they started. At the breakfast on Tuesday in Boston, before a scheduled board meeting, Kelly delivered the news to all the directors. "This is an opportunity I owe my family," he said. "I need to pursue it." The next day von Schack consulted with an executivesearch firm to begin identifying CEO candidates if, as seemed probable, Kelly took the BofA job.

Von Schack also told Kelly they needed his decision virtually right away. But Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday passed, and Kelly's letter of resignation didn't arrive. So on Saturday, von Schack called Kelly to establish a deadline: Kelly had 48 hours to decide if he was leaving. The board, von Schack said, had a meeting scheduled for Monday at 4 p.m. If they hadn't heard from Kelly by then, they would announce that he had resigned.

Meanwhile the BofA board began to have its second thoughts. Now that the bank had repaid TARP, regulators couldn't block the deal. Nor did anyone in the administration threaten any regulatory backlash. But BofA directors did call Geithner for guidance. Without expressing an opinion, Geithner suggested that the board check with Feinberg. On a conference call Feinberg again told the directors that they would have to be crazy to make the deal, and that the new CEO's first days would be spent getting pilloried by outraged members of Congress at sensational hearings.

For Kelly it was a case of damned either way. It was obvious that the BofA board was fractured. Several directors favored Moynihan -- who ultimately landed the job -- and were using the political climate as a reason to sabotage his deal. Kelly also had to consider the damage if he did get the package he'd been requesting. Regulators would no longer think of him as a distinguished banker, just as another CEO whose compensation the public reviled.

While Kelly was weighing these issues, the BNY board was considering its options. Among the internal candidates to replace Kelly, some board members favored the president, Gerald Hassell, a Bank of New York lifer who early in his career impressed Biondi as a lending officer in the CBS Building on the Avenue of the Americas. But the directors were also compelled to mount a search for outside candidates. And they feared that the process could drag on for weeks or even months, and that it might end up being highly expensive if they chose an outside candidate and had to buy him out of his contract. Pointedly, they wanted to avoid the mess that the Bank of America search had become.

When Kelly swept into the conference room that Monday and pleaded to keep his job, he gave the board an out. Yes, they were stung by his betrayal. But they justified taking him back by saying that it would be better for BNY not to change leadership while the economic recovery was still fragile. After Kelly was excused from the meeting, the general sentiment on the conference call was relief. Instead of the press release announcing Kelly's departure, employees got an e-mail that same afternoon from the boss. It said, "I firmly concluded that my place is here at BNY Mellon."

The board's motive for taking Kelly back -- not wanting to disrupt the bank's operations and management, and hoping to avoid a potentially messy succession -- was a weak one. They now had to worry about Kelly's loyalty. And the relationship between the CEO and his board would turn increasingly suspicious and adversarial.

Two days after Kelly returned, he had dinner with three directors: von Schack; John Luke, CEO of MeadWestvaco (MWV, Fortune 500), who chairs the governance committee; and Catherine Rein, a former top executive at MetLife (MET, Fortune 500) and a 30-year veteran of the board. They expressed their alarm at his flirtation with BofA. The directors told Kelly he would have to spend time "mending fences" with them -- and were alarmed when Kelly seemed surprised. They also informed Kelly that if he were to leave, Hassell would replace him as CEO. Hassell, they told Kelly, had just the skills they prized: He knew the complex custody business intimately and spent every waking hour working to please customers. Kelly would need to work extremely closely with Hassell.

But the warnings didn't chasten Kelly, who bridled more than ever under the board's authority. In June 2010 the three-year freeze on committee chairmanships expired. Kelly recommended to von Shack and Luke that the board change the chairs of two committees -- Rein, who heads the audit committee, and Nicholas Donofrio, a former IBM (IBM, Fortune 500) executive who leads the risk committee. After a brief discussion the board rejected the suggestion on the grounds that the two chairpersons had recently received excellent evaluations from their committee members. Von Schack reminded Kelly that it was the job of the independent directors, excluding the management members, to choose committee chairs. The incident didn't win Kelly any goodwill in the boardroom.

The directors began to fret that BNY Mellon was losing talent. Around the time of the tiff over board chairs, two potential future CEO candidates left. Ronald O'Hanley, the asset-management chief, departed for Fidelity. And the head of wealth management, David Lamere, left without taking a new job. Kelly took a "no big deal" attitude in explaining their exits to the board. But to the directors, it was a very big deal. The board had been pressing Kelly to improve management's bench strength. Suddenly two possible future CEO candidates were gone.

In replacing O'Hanley, Kelly managed to anger one of his biggest customers. The CEO announced in August 2010 that he had recruited Curtis Arledge from BlackRock, the world's largest asset manager. Kelly lured Arledge with an over-the-top compensation package that could pay him more than $30 million in less than two years, as well as promises to groom him as a successor. In the late 1980s, Arledge had been an early BlackRock employee, but he had left and later overlapped with Kelly at Wachovia. He'd been hired back at BlackRock in 2008 and just eight months earlier had been promoted to a new role handling the firm's big fixed-income clients.

BlackRock's CEO, Larry Fink, and its president, Robert Kapito, were furious. They hated changing the cast that served their customers. Most of all, they were incensed that Kelly had the audacity to raid a big client without so much as a courtesy call. After hearing that Fink and Kapito were upset, Kelly took Hassell and went to see them at BlackRock's offices on East 52nd Street. But when Fink vented his frustration, Kelly took a cavalier "it's just business" approach that did nothing to soothe Fink's ire.

That kind of imperious behavior repeatedly caused Kelly to clash with his board too. For example, Kelly was appalled by the condition of BNY's headquarters, in a 1932 art deco building on the corner of Wall Street and Broadway. He explored different options, from a sweeping renovation to the construction of a new building -- developments the board first learned about from a news article in May 2010. Kelly talked incessantly about his desire to move to an expensive, ultramodern headquarters, annoying the board to no end. Finally, this past summer von Schack informed Kelly that the board didn't feel it was a good time to spend a lot of money on relocating.

In December 2010 the compensation committee collected its annual written appraisals from the 12 independent directors. Many of the reviews were extremely critical. So in February of this year the board assigned five directors to meet with Kelly and discuss the poor evaluations. The board believed it was sending him a major warning signal.

According to people who've spoken with Kelly since his dismissal, however, he didn't think the meeting was a warning. Rather, he viewed it merely as his annual review, and a good one at that. Indeed, the board gave him a $5.6 million bonus for 2010, including 100% of his target based on his individual performance.

Since late 2009 the directors had been pushing Kelly to hold a big management meeting to fully present his strategic plan for how BNY would grow. At first Kelly resisted, arguing that he needed to focus on addressing regulatory issues and shoring up the balance sheet. But even before the review in February, the directors began to increase the pressure. The board wanted to know how Kelly planned to control the rising expenses that were eating into profits. They viewed the strategy session as a crucial test.

Finally, Kelly scheduled the conclave for June 2011 at the Doral Arrowwood resort in Rye Brook, N.Y. But it was Hassell, as well as other lieutenants, who handled the big presentations and who showed the surest mastery of how to raise BNY's lagging profitability. For the board, the meeting was further evidence that their backup candidate was really their man. Kelly took a passive role.

The end of the union

If the Kelly saga has a tipping point, it came on the evening of the presentations at the Arrowwood. The board was already worried that Kelly had become a divisive figure. After dinner several top executives quietly approached directors and complained about Kelly's leadership, charging that he played favorites. Hassell was not among the grousers. "He wouldn't complain if his fingers were being cut off," remarks an insider who knows him well. But the board was alarmed. In the days that followed, von Schack initiated confidential meetings with several more managers and heard much the same story. It became clear that there were problems brewing.

One example was the way Kelly treated the general counsel, Jane Sherburne, a high-profile hire who joined BNY in May 2010. Sherburne had served as GC at Wachovia and remains highly respected in Washington from her days as a former White House special counsel in the Clinton administration. In addition to her role as general counsel, the board insisted that Sherburne take on the position of chief of government affairs -- which meant infringing on a role that Kelly had enjoyed filling.

More than once Kelly openly denigrated Sherburne, to the distaste of the board. While discussing one issue, he remarked to directors that "Jane should have caught that." Another time he remarked witheringly that "Jane has to make changes to get used to our culture." The board, though, felt Sherburne missed nothing and considered Kelly's criticisms vindictive.

The final blow came in early August of this year when Kelly presented to the board a plan to lay off 1,500 employees -- just one day before he made it public. The move was a shock to the directors. They saw it as an unplanned, reflexive reaction to criticism from Wall Street. It hadn't been discussed at all at the strategy session. The board felt that the CEO was forcing its hand.

On Aug. 30, von Schack and Samuel Scott, head of the human resources committee and the retired CEO of Corn Products (CPO), went to Kelly's office. They told Kelly that the board wanted him to leave. Kelly's reaction was total amazement. When he asked why, the directors simply said that the board had lost confidence in him to the point where he had to resign or be fired. Gerald Hassell was being promoted to CEO. They declined to give further explanation.

In retrospect, the union of Bob Kelly and Bank of New York Mellon was a classic case of miscasting. The board ultimately didn't want a visionary in charge so much as an operations mastermind. "There was a mismatch between Bob and the process-oriented culture" of BNY, says one of his friends. By pursuing the BofA job, Kelly made it clear that his heart wasn't with Bank of New York Mellon. It was only a matter of time before the relationship dissolved.

Kelly's friends say he has no desire to retire, even after pocketing his full severance and retirement benefits worth $34 million. He is regrouping and hopes soon to be back where he feels he belongs -- running a large financial company. To improve his odds of success, he should choose his next board carefully.

This article is from the December 12, 2011 issue of Fortune. ![]()