|

Masterpiece Theater

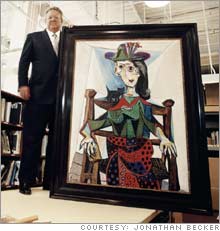

How Sotheby's CEO Bill Ruprecht rescued the auction house from the brink of disaster - and supercharged the stock.

(FORTUNE Magazine) - Every morning around 5:30, Bill Ruprecht starts his day pretty much the same way: He pulls an egg from under a chicken's bottom. The CEO of Sotheby's Holdings (Research) has 25 hens and two roosters living in the yard of his home in Greenwich, Conn. In a neighborhood where the collecting habits veer more toward Picasso and Renoir, Ruprecht's eggs may seem a bit unrefined. But to a gentleman farmer like him, they are art.

"Just look at the color of this one," he says one spring morning, several hours after his dawn rounds. He's peering down at a green egg, placed on his desk at Sotheby's headquarters in New York City. Smooth and spotless, it was laid by an Arauncana chicken, a special breed from South America. "I think this is just beautiful," he says, admiring the hen's work. Directly above him hangs a masterpiece, a portrait by Lucian Freud of his troubled son, Ali. At auction it would fetch around $3 million. The face is disturbing----off-kilter and twisted. It's an odd scene: the Freud peering crookedly down on Ruprecht and his egg. Yet in a room through which great works routinely pass, this barnyard hatch is right at home. Ruprecht paid a Sotheby's expert to design a special carton for his daily picks: a clear plastic box to show off color and texture; a label with two grainy, sepia-tinted photographs, one a headshot of a chicken, the other a closeup of an egg. It is definitely over the top, but like all collectors, Ruprecht is unabashed about his compulsion: "What can I say? I like chickens." Perched atop this 262-year-old auction house, Ruprecht, 50, has an unobstructed view of a strange world. He sees--almost daily--vast fortunes exchanged for objects whose lure is ultimately inexplicable. Who knows the draw of a Rothko? Or a Pollock? Or a Jeff Koons sculpture of Michael Jackson with his pet chimp, Bubbles? For nearly 300 years, Sotheby's has watched as each generation has changed what we see as art. It has been the trading post for the world's great masterpieces--an extraordinary nexus where the money and desire of the rich and powerful meet. This is where the Duchess of Windsor's heirs sold her famous jewels, where the Kennedy kids unloaded their father's golf clubs, where Andy Warhol's cookie jars fetched hundreds of thousands. Yet in the world of auctioneering, the question is not "What is art?" It is "How much will you pay for it?" So it should come as no surprise to anyone who knows the auction business that Ruprecht's eggs are for sale. If history chooses to remember Bill Ruprecht, he'll go down for this: saving Sotheby's. Six years ago he took on one of the worst jobs in corporate America. Before Enron, Tyco, and WorldCom, Sotheby's was the modern era's most notorious case of corporate corruption. Ex-CEO Dede Brooks famously colluded in the back seat of a car with Christopher Davidge, the CEO of archrival Christie's. Brooks pleaded guilty to price fixing; her testimony later helped send real estate tycoon Al Taubman, Sotheby's ex-chairman, to prison. (Davidge and Christie's received immunity in exchange for their cooperation.) The scandal nearly destroyed Sotheby's. The fines and lawsuits it faced were huge. "There has been a toll on us that no one outside the company will ever fully understand," says Susan Alexander, Sotheby's head of human resources, who worked with Brooks for 16 years. As the CEO chosen to right this damaged ship, Ruprecht managed a series of 11th-hour saves to keep Sotheby's afloat. Once he had just 12 hours to come up with the cash to make payroll. "It's like you've walked into a burning building and you have to save everyone in it," recalls CFO Bill Sheridan. "And that's what Bill did." If success in the art business is measured in dollars, then Ruprecht now qualifies as a grand master. Today, after years of struggle, Sotheby's has resurged. In March it reported that net income for 2005 rose 80% on a record $513 million in revenues. Since then the company's stock price has jumped 50%, to a recent $30 a share. A year ago it was at $16. But ultimately, Ruprecht's marker will not just be resurrecting Sotheby's. It will be where he takes the company from here. The art world is undergoing a stunning transformation. A whole new class of superrich--from hedge fund managers to Asian tycoons to Russian oligarchs--has entered the market. And they are whipping auction rooms into feeding frenzies. Last year an unprecedented 657 individual works of art sold at auction for over $1 million each. Sotheby's and Christie's combined sold $5.9 billion worth of art--up 168% in two years. "The market is moving so fast," says Marc Porter, president of Christie's Americas, "there are records being set at every sale." Already this year, the two auction houses have sales of more than $1.4 billion. Ruprecht's true test now is the way he guides Sotheby's across this new terrain. The buying craze has created huge opportunities, but auctioneering remains a boom-or-bust business. Having surmounted the obstacles of scandal, Ruprecht must conjure a business plan that can deliver the consistent growth his investors crave. (Christie's, which is privately held, doesn't have that same imperative.) And the question remains: Is the guy who saved the company from its past the right one to lead it into the future? "I remember one of my friends left the room and vomited," Ruprecht says, mopping the remains of his salad dressing with a piece of sourdough. It's a bright April afternoon, and he is recalling the aftermath of the Sotheby's scandal. Here in the chairman's office, where he is now digging into lunch, Ruprecht and a handful of other top managers found out that Dede Brooks was under investigation. "We walked in, and she was surrounded by all these people we'd never met before. And it was weird, because normally in meetings Dede did all the talking. But she said nothing. Then these other people--who we found out were lawyers--said, 'She can't talk to you anymore.'" That day, Jan. 28, 2000, is now seared into Sotheby's lore. What happened next? Chaos. "We were in shock," recalls HR chief Alexander. In a meeting over President's Day weekend, eight top executives holed up in a conference room to figure out what to do. "'Who's going to be CEO?' was sort of the elephant in the room," recalls Don Pillsbury, the company's general counsel, who was present at the meeting. "No one wanted to talk about it." The board, though, which was locked in its own struggle to find a new chairman, wanted the executives' recommendation. All of them agreed they didn't want an outsider. That would only reinforce the idea that Sotheby's was rotten to the core. They needed someone who knew the business and understood what the staff was going through--someone everyone could trust. Two other candidates were considered, but after two days of debating, Ruprecht--then chief of North American operations--got the job. His 20 years of service at Sotheby's made him the unanimous choice. His recollection of the way he was picked: "It's like they were asking for volunteers and everybody else stepped back--and I didn't hear the question." When he took the job, no one--not even Ruprecht--could say he was qualified for it. The son of a businessman and an artist mother, he had started at Sotheby's as a typist in the rug department, primarily because he needed a job and, at age 23, typing was his only skill. He rose through the ranks, first as an Oriental carpet expert, then director of marketing, then principal auctioneer. None of it prepared him for what he now faced: angry clients, disgruntled investors, a Department of Justice investigation, and a class-action suit headed by star litigator David Boies. His biggest problem was cash--or rather the lack of it. Auctioneering is an expensive business. There are significant overhead costs: the art experts, the storage facilities, the catalogs. On top of that, to win major consignments auctioneers must often pay money upfront to sellers in the form of guarantees or loans. Sotheby's costs in the wake of its scandal were monstrous. Its legal obligations were ultimately settled for $500 million--equal to the company's revenues last year. (Imagine how, say, Boeing would fare if it had to pay out fines equaling its $55 billion revenues.) The Taubman family, which is Sotheby's largest shareholder, picked up a portion of the tab. Still, things got so tight that more than once the company came within hours of being forced to shut its doors. "There were days when Bill would turn to me and say, 'I could come home today and there will be no company,'" recalls Betsey Ruprecht, his wife of 21 years, who also used to work at Sotheby's. At one point the company had to turn down a $40 million consignment because it simply didn't have funds to make the deal with the seller. To make matters worse, the art market itself slumped when the dot-com boom went bust. From 2000 to 2003 the company reported losses each year, a total of $307 million. "The system was close to paralysis," says Ruprecht. He was in almost constant negotiations with lenders to obtain credit. He slashed costs aggressively, cutting the staff by 30%, shuttering the company's Internet business, outsourcing its catalog-production facilities, and selling off its real estate brokerage to Cendant in a deal valued at $100 million. He even sold the company's headquarters building and leased back the space. All the while, Ruprecht had to put on a show to the outside world that everything was stable. After all, no one was going to hand over a $10 million Matisse to an auctioneer that might not be able to pay the electric bill. Even inside the company, Ruprecht never let on how close Sotheby's was to the edge. He somehow found enough money to keep his best people, like impressionism expert David Norman and contemporary art head Tobias Meyer, from walking out the door. Only three people--HR head Alexander, general counsel Pillsbury, and CFO Bill Sheridan--knew the true extent of the troubles. The turning point came in 2004, when Sotheby's auctioned the estate of Mr. and Mrs. John Hay Whitney, one of the great American family fortunes. It was an auctioneer's trove--everything from fine furniture to rare paintings. The star was Picasso's "Boy With a Pipe." Sotheby's original estimate predicted the painting would fetch $70 million. The night of the auction, the bidding went wild. When the gavel came down, the painting had sold for $104 million--a record for a painting at auction. The entire collection hauled in $213 million. Thanks in part to the Whitney windfall, Sotheby's that year posted its first profit of the new millennium. "I had to come down and see this for myself," says Ruprecht, stepping into the auction room on Sotheby's seventh floor. It's around 11 A.M. on a Friday morning, and a sale of Chinese contemporary art is underway. It was not expected to be particularly big--the total estimate is $6 million to $8 million--but starting at around 10:15, a steady stream of employees had been stopping by his office to tell him that "something is going on down there." Every seat is taken, and the crowd at the back is so thick that Ruprecht can barely find a spot to stand. At the front the auctioneer, Tobias Meyer, calls out the next item, Lot 10, "Comrade No. 4," oil on canvas by Zhang Xiaogang. Immediately, round blue paddles fly up: $45,000. $50,000. $55,000. The bids shoot past the $60,000 estimate. Five main bidders are going at it, furiously competing. $160,000. $180,000. $200,000. "New bidder at $300,000," Meyer announces pointing at the back of the room. When the final gavel comes down, the piece has sold for $419,200--seven times its high estimate. In auction rooms these days, the frenzy of the bidding can be spectacular. "There is a beautiful German word for this: nachholbedarf," observes Meyer in his office later. "It means the desire to make up for lost time." Among a new and emerging class of elite collectors, there is a sense of urgency--an immediate need for gratification and possession. Stevie Cohen, head of hedge fund SAC (who paid himself $500 million last year) is indicative of this new breed of rabid art buyers. Over the past five years Cohen has reportedly built a $700 million collection. According to one dealer familiar with his buying, Cohen has a hit list of additional masterworks that he wants to acquire. And he's hardly the only wealthy collector on the prowl. Recently a rich Russian woman arrived at Sotheby's and announced that she wanted to build a collection. The expert she met with suggested that she start slowly, with a few important pieces. Her response: "I want abundance." "I haven't slept in four days," Ruprecht says one morning. He looks wired, eyes glinting behind his wire-rimmed frames. Four days earlier, the owner of a $100 million art collection decided he wanted to sell it. He gave Sotheby's and Christie's 36 hours to come up with deals for him and told them he'd mull them over on the weekend, then make a decision. By Sunday night Ruprecht was so anxious about it that he sent the collector an e-mail----to which he got a terse response telling him to buzz off. Now Ruprecht's just heard the news: "So he called this morning and he said, 'The consignment goes to...." He pauses to build the suspense. From the way he's grinning, though, there is none. "Sotheby's!" Right now there is a sort of giddiness at Sotheby's. For the first time in a long time, Ruprecht is not worrying about a company in crisis. "Now I can look to the future--because I know we have one," he says. He has launched a sequence of sweeping initiatives, including stepping up Sotheby's presence in Russia and hiring expert Xiaoming Zhang away from the Guggenheim Museum to develop a business in contemporary Chinese art. He is also looking at new ways--outside the auction rooms--to bring in cash. Recently he started Sotheby's Diamonds, which sells jewels to retail customers, competing with the likes of Tiffany. In addition, he is looking to rent out the Sotheby's brand name in order to add some steady fee income. Already the company receives a licensing fee from Cendant for use of the Sotheby's label on its realty business. And Sotheby's traditional business has been set on a new course. Ruprecht is rolling out an innovative marketing plan for high-end clients. In April, Sotheby's sent membership cards to 40,000 such favored customers, offering free shipping on art, discounts on private jets, special access to museums, and other perks. At the same time, Ruprecht has refocused the company on high-end items----and eliminated the low end. Sotheby's no longer targets run-of-the-mill stamps and coins or everyday furnishings. It will still auction a set of china, say, but only as part of a larger estate or collection. As a result, the total number of lots sold at Sotheby's has fallen to 77,000 from 110,000 just a few years ago. It's a risky plan, to walk away from an established area of the business--especially considering that the competition has happily picked up consignments Sotheby's has dropped. (Christie's says its lower-end sales, which offer items for as little as $500, are among its most profitable.) So far, however, Ruprecht's bet is paying off: The company's average lot sale has grown by 50%, to $35,000. (Christie's is $20,000.) In the last quarter, Sotheby's net earnings rose 39%. Still, says Ruprecht, "in this business you can never breathe easy." Despite the rising stock price and clamoring auction rooms, there's a part of him that remains wary and distrustful. "This is a business of unanticipated events," he says. "We were in a bunker, we were being shot at every day. And now that it's passed, you can't believe you're still standing." In Sotheby's eighth-floor conference room, Ruprecht and a group of the company's executives are discussing expansion plans. Managing director Richard Buckley is making the case for opening an office in Moscow. "We've got Tina working out of the back of her apartment in the most status-conscious town in the world," argues Buckley. "We can't compete that way." Sotheby's has identified a large group of rich Russians--newly minted centimillionaires and billionaires--who own much of the wealth in the country and by all appearances are clamoring for artwork. (In 2004 oil czar Victor Vekselberg, in a private deal brokered by Sotheby's, paid $100 million for the Forbes family's entire collection of Faberge eggs.) The potential in Russia, Buckley says, is huge. But when pushed for his opinion on the Moscow office, Ruprecht grows visibly tense. "God forbid what the fixed infrastructure could do to us," he says quietly, fiddling with a paper clip. "It makes me shudder." He better than anyone knows how fragile the art game is--fragile, like an egg. |

|