Back to schoolCompanies that make money in education have had good friends in Congress. That may change under the Democrats.(FORTUNE Magazine) -- In the corporate world, there's a short list of obvious suspects who may face tougher times under a Democratic Congress, including Big Pharma and Big Oil. Then there are the not-so-obvious suspects - like what might be called Big Education. In fact, the stocks of companies that make their money educating America's college students have had a turbulent year. Look no further than the granddaddy of student lenders, SLM Corp. (Charts) - more commonly known as Sallie Mae -which fell some 13 percent through Nov. 7 and dropped another 5 percent on Nov. 8, as the news rolled in that the Democrats had captured the House.

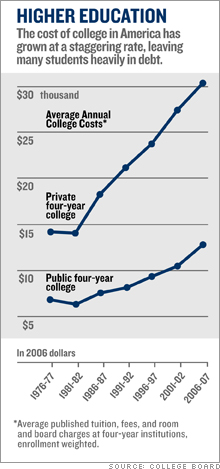

In Congress's last term, Republicans did not fully reauthorize the Higher Education Act, which governs many aspects of education finance, thereby leaving the door open for Democrats to change the laws. And change is indisputably part of the Democratic agenda. George Miller (D-California), who is likely to become the new chairman of the House Committee on Education and the Workforce, wants to cut interest rates on student loans in half. Last spring Senator Hillary Clinton (D-New York) introduced a Student Borrower Bill of Rights. Among its tenets are a cap on loan interest as a percentage of a borrower's income. "A Democratic majority will definitely have an opportunity to change student-loan law," says Michael Dannenberg, who directs education policy at the New America Foundation, a Washington think tank. It's no secret that change is needed. A just-released report commissioned by the Secretary of Education calls for "complete restructuring of the current federal financial aid system." Cost is a major culprit. Tuition has grown at double digits for more than a decade, and federal aid has not kept up, resulting in often crippling levels of student debt. As a blogger using the name "collegedebt4life" writes, "We went into debt to get an education so that we could get good jobs, and we find that we have mortgaged away the rest of our lives by taking out student loans." David Hawkins, who heads government relations at the National Association for College Admission Counseling, looks back to the 1960s, when Lyndon Johnson pushed to make higher education affordable by setting up the Federal Family Educational Loan Program, or FFELP, which encourages private companies to lend to students by providing government guarantees, and says, "We've reached another fork in the road." Big changes ahead Student advocates and Democratic leaders see some easy targets: Republicans, lenders, and for-profit schools. "The Republicans put a lot of effort into taking care of the lenders," says Miller. "But they forgot to take care of students and their families." Many claim that political donations by companies have corrupted a process that is critical to people's lives, not to mention the country's future. Jon Oberg, who recently retired as a Department of Education researcher, says, "The Higher Education Act has turned into a Student-Loan-Provider Subsidy Act." Another part of the problem, he says, is a "revolving door" between the DOE and industry. Certainly not everyone agrees with that. "We're part of the solution," says Bruce Leftwich, vice president of government relations at the Career College Association, which lobbies on behalf of for-profit schools. Tom Joyce, vice president of corporate communications at Sallie Mae, says students' interests are aligned with lenders'. "If more students attend college, the country wins, students win, and Sallie Mae will win," he says. And yet there's something unsavory about much of what has happened in the past few years. Both the student-loan industry and the schools are dependent on the federal government. Under FFELP, the government pays a lender 96 to 98 percent of the interest and principal it is owed should a student default on a loan. The government also guarantees lenders a certain level of income. In effect, the profitability of lenders is regulated by Congress. Because schools must meet government-set standards for their students to qualify for FFELP loans, they too have an incentive to lobby Congress. "They exist under the aegis of the rules," says Richard Lee Colvin, who runs Columbia's Hechinger Institute on Education and the Media. So it's not surprising that companies like Sallie Mae have become more and more visible in Washington. The Chronicle of Higher Education has reported extensively on the large donations the lending industry and the for-profit schools have made to Republican leaders like John Boehner, who was the chairman of the House Committee on Education and the Workforce until he became the party's House majority leader this spring, and Howard "Buck" McKeon, who took Boehner's place. Both are known as strong supporters of student-loan companies and for-profit colleges. Cozy relationships But there are also contributions that have gotten less attention. For instance, in 2006 three of the top six individual contributors to the National Republican Congressional Committee are lender Nelnet's president and its co-CEOs. Nelnet itself is the committee's largest corporate donor, according to research done by Dannenberg. Mike Enzi, the Wyoming Republican who is now the chairman of the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions, has a political-action committee called Making Business Excel. Top contributors are the employees of Sallie Mae, who gave $20,000; of Corinthian Colleges, who gave $15,348; and of Nelnet, who gave $10,000. According to PoliticalMoneyLine, the PAC has paid $121,129 since 2005 to Enzi Strategies, a political consulting firm owned by Danielle Enzi, who is Mike Enzi's daughter-in-law. (A spokesman for Senator Enzi says about a third of that was reimbursement for expenses, and adds, "Senator Enzi's actions are driven by what he believes to be the best interests of the people of Wyoming.") And there's the movement of political appointees among the DOE, lobbying firms, and corporations. An incomplete list includes Sally Stroup, who was the chief lobbyist for Apollo Group, which owns the for-profit University of Phoenix, before she was appointed by President Bush to oversee post-secondary education at the DOE. In the spring of 2006 she left to become the deputy staff director at the House Education Committee. Two other former top DOE officials, William Hansen and Jeff Andrade, have ties to FFELP lenders and the for-profit schools. All that clout may have manifested itself in several ways. Last February, Bush signed the budget-reconciliation bill, which cut $12 billion from student-loan programs - at least in part by raising student-loan interest rates. Lenders complain that they took a big hit too, but Wall Street didn't seem to think so. Sallie Mae's stock didn't fall at that time. Prudential analyst Charles Gabriel described the legislation as "barely nicking" margins. It was a "huge political victory for the industry," he wrote in a report. The bill also made life far more difficult for the only competitor to the FFEL program. That's so-called direct lending, under which the DOE makes loans directly to students, cutting out lenders. In the past few years studies by the Congressional Budget Office and others have reported that FFELP loans cost taxpayers more than five times as much as direct loans. Yet many Republican members of Congress have been reluctant to support direct lending. Miller, who has advocated unsuccessfully for direct lending over the past few years, chuckles when he's asked about it today. "I have a great deal of interest in the direct-loan program," he says. Other favors have been aimed at the for-profit schools. Just one example: Back in 1992, to protect students, a rule was enacted to prevent colleges from paying admissions officers based on how many students they enrolled. For-profits (and some not-for-profits) complained loudly about this. During Andrade's and Hansen's brief tenures with the DOE, they helped set up 12 safe harbors under which schools could partially get around the rule. Hansen also argued that the DOE could use "discretion" in determining fines for violations. A DOE spokesperson says, "The whole process was conducted in an open and transparent manner." For-profit scandal Even as protections like that one were rolled back, the drumbeat of scandal from the for profit sector got louder. Today chains like Corinthian Colleges and Apollo are facing lawsuits and investigations over allegations ranging from aggressive sales tactics to misleading students about job-placement rates and salaries. Says the Career College Association's Leftwich: "Investigations, bad news, some wrongdoing - that's universal across higher education." The episode that may say the most about higher education and Washington, though, involves an arcane provision that is known as the 9.5% loophole. It came into existence in the days of high interest rates, when Congress guaranteed a 9.5% return to lenders who made student loans using the proceeds of tax-exempt bonds issued before October 1993. It was supposed to be a short-term incentive. But in 2003, Oberg, then a DOE researcher, noticed (while digging through SEC filings) that the volume of outstanding loans upon which lenders were collecting 9.5% was actually growing. It turns out that lenders, of which Nelnet is the most prominent, were using a variety of accounting and financial maneuvers to keep qualifying for the subsidy. In some quarters that wasn't exactly a secret. In fact, in 2003, Nelnet wrote to the DOE, describing its "Project 950" in detail and asking for approval. Whether Nelnet got approval, as it claims, or not is in dispute, but at best the DOE didn't object. The appetite of some in Congress for shutting down the subsidy wasn't much higher. Until 2005, when rebellious members succeeded in passing an amendment, Boehner supported the lenders. The practice was finally abolished in 2006. Yet because of the delays and because existing loans that qualify through the loophole will still qualify, the New America Foundation estimates a total cost to taxpayers in excess of $6 billion. That's $6 billion that could have helped students attend college. A Nelnet spokesperson wouldn't comment on this issue but said, "The private sector has brought enormous value to the education services industry." The story has a final twist. In September the DOE's inspector general issued an audit of Nelnet that called for it to give up $1.2 billion in 9.5% payments. On the same day, it issued another critical audit, this one of the DOE subsidiary that oversees the FFEL program. Among other criticisms, the IG said that the DOE "emphasized partnership over compliance" in its relationships with the entities it was supposed to monitor. For students and their parents, the important question is whether politics can be part of the solution. It's not clear. The only thing that's certain is that Big Education "will spend what it takes to get themselves some new friends," says Barmak Nassirian, associate executive director at AACRO, a professional group for college administrators. Working families vs. big business. reporter associate Patricia A. Neering contributed to this article. From the November 27, 2006 issue

|

|