GAP: Decline of a denim dynastyThe inside story of how the Fisher family turned Gap into one of America's top retailers--then pulled the strings as it unraveled.(Fortune Magazine) -- On a cold September day in 1941, Donald Fisher, the founder of Gap Inc., was fishing on a Northern California beach. Suddenly, 12-year-old Don hooked a bass so big his brother Bob thought it was a shark. "Let it go!" his brother screamed. "No way," Fisher later wrote. "I didn't care if I'd hooked a submarine, losing was not an option." He reeled in the "shark," motivated not by landing a prize fish but by the thought of letting it slip from his grasp. "The fear of losing pushes relentlessly from behind," he wrote. More than 65 years have passed since that day on the beach, and nearly four decades since Don Fisher and his wife, Doris, opened their first Gap store, a San Francisco shop selling Levi's and records that grew into an iconic American brand. Yet if that fear of losing is still what drives Don Fisher, he must be feeling pretty motivated right now. At 78, an age when he probably expected to be enjoying a few victory laps, Fisher and his family are now struggling to reel in yet another thrashing beast. This time, it is Gap itself.

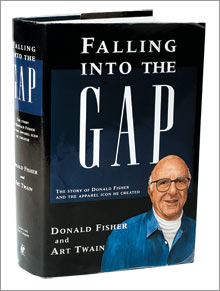

From its high point, when Gap's classic American style was so ubiquitous that it was worn to the 1998 Oscars and mocked on Saturday Night Live, the company has sunk into a slump that threatens to derail the Fishers' proud legacy. The past five years have featured long stretches of falling same-store sales, a stagnant stock price (down 14% in the past two years alone), and a strong feeling among much of the analyst and private-equity community that Gap (Charts) has too many stores and its three main brands--Banana Republic, Gap, and Old Navy--may be better off broken up. "Gap has its back to the wall," says Bob Buchanan, retail industry group leader at A.G. Edwards. In the 2007 Brand Keys customer loyalty engagement index, Gap ranked 355th of 362 brands surveyed, while rivals H&M and J. Crew (Charts) ranked 16th and 30th, respectively. It is all damning evidence that the $15.9 billion company has lost its way. For a long time now, though, the scribes penning the retailer's saga have spilled most of their ink on the messy departures of two high-profile CEOs: polar opposites Millard (Mickey) Drexler and Paul Pressler. Yet the fact is that behind every major decision the company has made, the good ones and yes, the bad ones, is the famously private Don Fisher and his family, who hold 34% of Gap's stock (worth over $5 billion) and three of 12 board seats. Says Drexler, who now runs rival J. Crew: "Don Fisher had two claims to fame: One was hiring me, and the other was firing me. I find it quite ironic." That's not the only irony: Don--who after an early failed venture with his own father vowed "never to partner with family members again"--was part of the board's January decision to name Bob Fisher, Gap's chairman and Don's firstborn son, interim CEO. How did the Gap get here? To understand that, you have to understand the Fishers. Their story shows how a family banded together to build one of America's most successful retailers--and lays bare what can go wrong when a handful of well-intentioned billionaires run a huge public company like a family fiefdom. Family ties "The Fisher family has a thing for tradition, almost to the extreme," writes Don Fisher in his 724-page autobiography, "Falling Into the Gap: The Story of Donald Fisher and the Apparel Icon He Created." Fisher and his co-author, Art Twain, spent six years working on the book, then decided--under family pressure--not to publish it, instead sending out copies only to close associates. Through the book and interviews with 49 people--including 19 former and current executives--Fortune was able to get a rare glimpse into the family's world. (The Fishers refused to be interviewed but responded to factual questions through a spokesperson.) It's a tight-knit clan. Don and Doris, who have been married for almost 54 years, and their three sons, Bob, Bill, and John, all own homes within blocks of one another, and everyone skies together at Sugar Bowl, the Tahoe resort the family has a stake in. All three sons attended Phillips Exeter Academy, Princeton, and Stanford Business School; all are married to their first wives and have several children; all have worked for the family in some regard. "If you ask me what their greatest achievement is," says James Steyer, CEO of a nonprofit called Common Sense Media and a family friend, "it's not Gap, it's their boys and grandchildren. It's not even a close call." Although the Fishers are relatively new money, they are also old-time San Franciscans in a culture that abhors showiness. Their social circle includes everyone from Dianne Feinstein to Charles Schwab to George H.W. Bush, Fisher's onetime campmate at Bohemian Grove, the annual all-male gathering of the power elite. Don and Doris's home, while stately and situated in Presidio Heights, with a view of San Francisco Bay and the Golden Gate Bridge, boasts no Corinthian pillars or sweeping staircases. Bob Fisher's home--in the same neighborhood--looks a lot like his dad's. That's no coincidence: Don not only talked Bob into buying it but also helped design the floor plans. (He scouted out locations for his other sons' homes as well.) Board member Doris, now 75, still shows up at Gap headquarters behind the wheel of a decades-old wood-paneled station wagon. And Don, the plainspoken patriarch, never misses a chance to save a buck: Anne Gust Brown, Gap's former general counsel, remembers seeing the Fishers at a gas station, a mattress tied to the top of the car because Don was outraged by the $25 delivery charge. "They looked like the Beverly Hillbillies," she laughs. The comparison to the Clampetts, however, ends with the Fishers' taste in art. Between Warhols, Gerhard Richters, and other important works, the Fishers have "one of the great collections of contemporary art in the world," says Neal Benezra, director of San Francisco's Museum of Modern Art. SFMOMA houses the Fisher Family Galleries on the museum's fifth floor, and, Fortune has learned, the Fishers are in talks about building a museum in San Francisco's Presidio. Gap's Embarcadero headquarters, overlooking San Francisco Bay, is a tribute to the family's love of art--and of real estate. The $136 million Robert Stern-designed limestone building was completed in 2001 and is dotted with valuable Lichtensteins, a monumental Richard Serra sculpture, and other works from the Fishers' private collection. (Asked the name of one metal sculpture, a receptionist says, giggling, "I call it 'Pieces of My Car.'") The Fishers pay Gap $892,000 a year in "rent" to show their art, according to the proxy. Although the building's opulence gives it the feel of a company on the rise, the opposite is true today: Gap has become a mass-appeal retail company that is more about discounts than distinction, with stores that A.G. Edwards's Buchanan characterizes as drowning in a "sea of markdowns." It is exactly the vision that Don Fisher sought to avoid back in 1983, when his 550-store chain fell victim to price wars and poor-quality merchandise. "I wanted a clean, classy full-price business," writes Fisher, "not the schlocky off-price operation we had become." It is a fate that, for all Fisher's success, has come back to haunt him time and again. Pants and properties Don Fisher was never much of a clotheshorse--and in fact didn't get into retail till just shy of his 41st birthday. He was a businessman who actually did fall into the Gap. The oldest of three brothers raised in a comfortable San Francisco family, Fisher was a great swimmer and a party boy whose nickname at the University of California at Berkeley was the "Horny Fish." He was also a jokester who ended up in jail for such antics as driving his car through a casino's open doors and throwing a can of beer at a Mexican matador. After college, the prematurely balding Fisher did what was expected of him. He married Doris, a childhood friend, and went to work in the cabinet business his mother, Aileen, had inherited and his father, Sydney, was running. "I didn't have much choice," writes Don. "I had no money, and I didn't want to disappoint him." "Symphony Syd," as Don's friends called him for his silky demeanor, wasn't much of a businessman; he had a knack for sales but always bid low to win the job. Eventually, when he was forced to sell the business to pay off creditors, Don persuaded him to convert the factory into an office building. Next the two, along with Don's brother Bob, began building luxury homes together. But their differing approaches drove Fisher crazy. "I couldn't stand working for my father any longer," he writes. "I was on the brink of seeing him as my enemy and had to be my own man." |

Sponsors

|