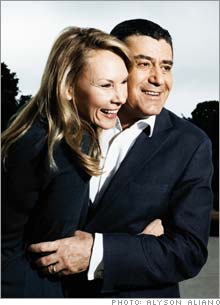

The man with the golden gutHow Haim Saban, a flinty self-made billionaire, plans to turn Univision into the next great network - and put Hillary Clinton in the White House. Fortune's Stephanie Mehta reports.(Fortune Magazine) -- "May I offer you a cucumber?" That's how Haim Saban begins his account of the battle for Spanish-language media company Univision. It's an unconventional icebreaker, to be sure, but then again, much about the 62-year-old media entrepreneur is out of the ordinary: He gossips with Rupert Murdoch, vacations with Bill Clinton, throws parties with Steven Spielberg, and confers with former Israeli Prime Minister Shimon Peres.

He is worth an estimated $2.8 billion. Yet he eschews power lunches at the Grill in Los Angeles, choosing instead to eat sushi nearly every weekday with his driver, Laine Burton. The cucumber, it turns out, is part of an afternoon snack that also includes tomatoes and pepper jack cheese. "It's very low fat," says the fitness-conscious Saban. (He works out an hour or more daily.) "He could be the subject of a movie or a TV series," former President Bill Clinton told Fortune. "He's a fascinating character." Despite this ready-for-prime-time personality, Saban (sa-BAHN) has preferred to work behind the scenes. But two events are changing his ability to stage-manage far from the headlines. First, he is attempting to put Senator Hillary Clinton in the White House at a time when Senator Barack Obama is catching fire with L.A.'s Gulfstream liberals. Second, he and a consortium of private-equity players bought Univision, the largest Hispanic media company in the U.S., in March. The $12.3 billion acquisition battle strained Univision's relations with Mexican media giant and rival bidder Grupo Televisa (Charts), its main supplier of programs. The deal, which should have been a snap to close, has been singled out for some harsh regulatory treatment: Before the Federal Communications Commission signed off on it, the buyers had to agree to pay a hefty $24 million fine to settle charges that the network wasn't airing enough children's programming. Univision claimed it was meeting its educational mandates by running Complices al Rescate (Friends to the Rescue), a telenovela about 11-year-old twin girls who swap identities. Not exactly Plaza Sesamo. Fortified by his veggies and cheese, Saban explains why Univision and New York's junior Senator will both be winners in 2008. First, Univision: Under founder A. Jerrold Perenchio, the company had grown to nearly $2 billion in annual revenue, but Saban, who put in a chunk of his own money, and his deep-pocketed partners - Providence Equity Partners, TPG, Thomas H. Lee Partners, and Madison Dearborn - think Univision can still grow sales in the double digits. That would be a tall order for ABC, CBS, or NBC, but Saban isn't sweating it, because by the year 2010, the Hispanic population will grow 17% and will be spending about $1.1 trillion a year. The trouble with Saban's vision is that for now, only a fraction of the top U.S. brands advertise on Univision, partly because some key decision-makers picture its viewers as blue-collar immigrants rather than affluent suburbanites. "Marketing to Hispanics is something that companies need to make a priority," says Caleb Windover, managing director of ad buyer MediaVest's multicultural division. Before Madison Avenue will open the spigot, Univision needs a face to woo its media buyers. That job falls to new CEO Joe Uva, who most recently ran ad-buying agency OMD. Like his predecessor, Perenchio, Uva doesn't speak Spanish, but he will go out and personally press the flesh with marketers and suppliers. The 76-year-old Perenchio, who declined comment, hadn't been involved in day-to-day operations at Univision for years before it was sold. The company hasn't named a chairman, and it won't be Saban, who isn't interested in titles. That doesn't mean, however, that he won't be involved. He thinks Univision is leaving money on the table by barely charging the cable and satellite operators to air the network, and he shared a bombshell proposal with Fortune: Charge the operators an unprecedented $1 per subscriber per month for Univision. To put that in context, CBS earlier this year reportedly got some small operators to pay about 50 cents per viewer per month. Saban boldly suggests that Univision is worth more. "If you are an operator and you have the guts to commit suicide and remove Univision, you'll be... " He trails off, then pretends to wash his hands, the gesture for finito. Cable operators are sure to balk, but Saban says Univision delivers big market share while CBS, NBC, ABC, and Fox have lost viewers to cable, the Internet, and other media. If his fee scheme is successful, Univision could add $1 billion in annual revenue. It turns out that Saban has had his eye on Univision for the past three years. Back then he went to see the press-shy Perenchio at his Bel Air, Calif., home to let him know of his interest in buying Perenchio's stake in Univision. (The two men aren't close but have common friends, such as CBS CEO Les Moonves.) According to Saban, Perenchio said his Univision holdings weren't for sale but encouraged him to call every month or so, "just to say hello." So Saban started checking in every two weeks. But he wasn't the only one interested in Univision: Wall Street had long thought Televisa, the Mexican television empire that helped Perenchio acquire Univision in 1992 and thus owned 11% of the company, would be a logical buyer. And indeed, Televisa, along with Bain Capital and Bill Gates' investing arm, Cascade, did put in a $12.2 billion offer for Univision, only to be outbid by Saban and his partners by about $170 million, or 50 cents a share. Just to show that there were hard feelings, the Televisa rep on the Univision board voted against Saban's offer. Fortunately, the man likes a challenge. In 2003 he led the acquisition of ProSiebenSat.1, a moribund German broadcaster once controlled by the Kirch group. Saban says he had a hard time getting ProSieben's banker to even send him a deal book, he was such a long shot to win the property, which was in bankruptcy. "All the big muckety-mucks were there," Saban recalls, ticking off the names of A-list moguls whose companies had looked at ProSieben. "You know Mel Karmazin? Rupert Murdoch? Michael Eisner? Dick Parsons? They were all there, and they all went away." Once he won ProSieben, Saban set about transforming the company, though not all his ideas were well received. He sent its dour newscasters to his friend Murdoch's Fox News to be schooled in pepping up their delivery. He urged management to create a German version of the Colombian telenovela Yo soy Betty, la fea (known to U.S. audiences as Ugly Betty). The German version of the show, Verliebt in Berlin (In Love in Berlin), turned into a huge hit for ProSieben's Sat 1 channel. This spring, as the Univision deal was closing, Saban also completed the sale of his stake in ProSieben to KKR and Permira for about 29 euros a share - more than quadruple what he paid for the company four years ago. A ribald polyglot who liberally peppers his conversation with phrases in French, Hebrew, Italian, Spanish, and four-letter words, Saban isn't a numbers guy or even an operational whiz. But with ProSieben and now with Univision, he is showing that entrepreneurial skills and taste-making instincts can succeed on a big scale - and he's doing it with his own money, plus the vast sums of private equity floating around right now. "This is the story of big-time entrepreneurship," says Jonathan Nelson, managing partner at Providence Equity Partners, which invested in ProSieben with Saban and now is a member of the Univision consortium. "There isn't one model for corporate success anymore. Haim offers a more interesting and human model." Nelson is a seasoned media and telecom investor - his portfolio includes MGM and Warner Music - and he certainly doesn't need access to Saban's capital. Still, Nelson says Saban, with his ability to spot big media opportunities, was the first person he called when Providence was checking out Univision. Saban's ability to seamlessly glide from East Coast bankers to Israeli pols to Hollywood media moguls can be traced to his peripatetic youth. His father was a toy seller - a child can't imagine a better job for a parent - and the close-knit Jewish family lived modestly in Alexandria, Egypt. When Saban was 12, the Suez Crisis of 1956 erupted, forcing the family out of Egypt to Israel by way of Greece. They left behind everything, and times were so bad, says Saban's wife, Cheryl, that his mother couldn't even rustle up two pans so that she could bake him a cake to celebrate his bar mitzvah. The experience of poverty "is so deep in the family psyche," says his wife of 20 years - they met when she took a job as his assistant and married a year later - "at some time in Haim's young life, he decided that was never going to happen to him again." He got his start in show biz as the manager of an Israeli Beatles cover band called the Lions. He came to L.A. in 1983 and began a career as a self-described "cartoon schlepper" who built Japan's Mighty Morphin Power Rangers into Fox Kids, a programming joint venture with Rupert Murdoch that, um, morphed into a national cable network. Disney (Charts, Fortune 500) later purchased it for a stunning $5.2 billion, and Saban pocketed some $1.5 billion - money he has donated to several pet causes, including $7 million for the construction of a new Democratic National Committee headquarters building in Washington, D.C. Saban wasn't even interested in politics until he met Bill Clinton during his first term as President. The meeting was brief, but the friendship grew as Clinton made dozens of trips to California during his presidency. Clinton, Saban says, ignited his interest in using his resources to find solutions to strife in the Middle East. He soon became the Democratic Party's largest single donor. "I don't say this lightly," says Terry McAuliffe, head of the Democratic National Committee at the time. "Haim Saban saved the Democratic Party." Now Saban is turning his energies to Hillary Clinton. "I think he likes her better than he likes me," jokes Bill Clinton. But as he talks about Saban's support of Senator Clinton, the former President turns serious. "It is something that" - he pauses - "I can hardly talk about it because it really makes me emotional, 'cause he has genuinely come to love and respect her." Under current campaign-finance laws, donors can give only $2,300 to a candidate's primary run and another $2,300 for the presidential run. That means that to raise the big money, fundraisers like Saban have to knock on a lot of doors. "He makes all those miserable calls you have to make to get your friends to contribute," says Steven Rattner, managing principal of New York-based investment firm Quadrangle and an active Democrat. "He's quite relentless." For Senator Clinton's run, he has hosted events at his office and at his Beverly Park estate, a sprawling mansion in a gated community that is also home to Reba McEntire, Rod Stewart, Sylvester Stallone, Denzel Washington, and Viacom chairman Sumner Redstone. Saban, Steven Spielberg, and News Corp. (Charts, Fortune 500) executive Peter Chernin are hosting another fundraiser for Clinton in late May. He tells of traveling with her on his jet (she paid her way, he insists) when the pilot informed him an engine had gone out. Saban says he excitedly conveyed this information to Clinton, who thanked him and went back to her reading. He later asked her how she managed to stay so calm. According to Saban, Clinton explained that she was in the middle of a good paragraph in her book and that there was little she could do about the situation, so why freak out? "This is magnificent!" Saban practically shouts. "This is what you want in a leader. Nobody touches her. She's really the most qualified candidate." Some of the Clintons' former supporters disagree, most notably fellow mogul and master fundraiser David Geffen, who is backing Barack Obama. (He has also made a contribution to former Senator John Edwards's campaign.) The same week Geffen threw a star-studded fundraiser for the Illinois Senator, he trashed the Clintons, essentially calling them liars, in an interview with New York Times columnist Maureen Dowd. Saban's response is uncharacteristically subdued. "I'll make three observations," he says crisply. "David is a friend of mine. David is a very smart guy. I don't understand where he's coming from. But let's you and I agree that there are other aspects of this race that are interesting beyond what David Geffen is saying." Perhaps he's being polite, or maybe he's trying to stop himself from gloating: Clinton is running only slightly ahead of Obama in money from lawyers, and she's trailing in donations from teachers, according to data from the Center for Responsive Politics. In the entertainment industry, though, she's outgunning her rival by about 22%. Much of that can be attributed to Saban, who by early May had raised $1 million for Clinton, the most by any individual fundraiser. Call it the Haim effect. Will the Haim effect also work its magic on Univision? "I would like to stress that I am the smallest investor in Univision. Every deal needs a face," he says. (When the choice is one of four private-equity firms or Saban, the guy who wrote the music for Inspector Gadget, can you blame the press for picking Saban?) Indeed, the other investors each put up about $1 billion of the capital for the deal, with Saban kicking in about $300 million of his own money. The group borrowed the rest. But Saban's charm could also be a valuable asset to Univision in its efforts to smooth relations with Televisa, run by Mexico's powerful Azcárraga family. The late Emilio Azcárraga Milmo, a billionaire known as El Tigre, not only invested in Univision but also supplied it with Televisa's popular (and occasionally risqué) telenovelas. His son, current Televisa CEO Emilio Azcárraga Jean, sat on the Univision board for several years until he abruptly quit in May 2005. The relationship between the companies deteriorated from there, and Televisa sued Univision, saying it wasn't getting the royalties it deserved for its programming. "I know both sides" of that conflict, says Murdoch. "I would say it is very, very difficult, but if there's anyone who can mend that fence, it would be Haim." As it turns out, Saban is already trying to make nice with Televisa. For starters, he has an existing relationship with the Mexican broadcaster, which aired his kids' programs in the 1990s. He also speaks Spanish. But mostly Saban brings to the table what business school professors might blandly call "people skills," though in Saban's hands the delivery is anything but bland. During a visit to Televisa before the deal closed, for example, Saban and associate Adam Chesnoff toured a school the company runs for teaching the art of producing telenovelas. The two men watched a taping, and between scenes Saban danced on the set with a dozen actresses. Talk about breaking the ice. Perhaps next time he'll offer them a cucumber. From the May 14, 2007 issue

|

Sponsors

|