A pretext for revengeHewlett-Packard says former VP Karl Kamb betrayed the company. He claims HP got his private phone records and spied on Dell. Fortune's Nicholas Varchaver reports.(Fortune Magazine) -- In October 2003, Karl Kamb, then a 40-year-old Hewlett-Packard vice president, made a presentation that persuaded CEO Carly Fiorina to take her company into a new line of business: flat-panel televisions. Rival computer makers were plunging into consumer electronics, Kamb argued, and HP needed to jump in before it was too late. Only three months later, in January 2004, Fiorina staged her own glitzy performance, using her keynote address at the Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas to announce the launch of HP's flat-panel-TV business. "Most living rooms are in desperate need of a digital makeover," said Fiorina, who showed off an HP prototype playing a videotaped skit in which Carson Kressley adapted his "Queer Eye for the Straight Guy" persona to riff on digital electronics.

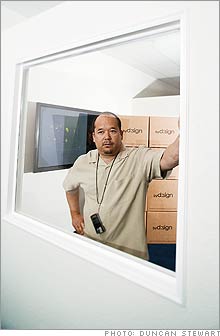

Today that triumphant moment for Kamb and HP is a distant, sour memory. Fiorina was replaced in 2005, and HP's TV business has failed to take off. Now the computer giant finds itself locked in a bitter and bizarre lawsuit with Kamb - a so-far little-noticed conflict that threatens to revive the most mortifying memories of HP's 2006 "pretexting" scandal and become a blot on the company's otherwise brilliant business comeback. It's a story of intrigue, duplicity, and vindictive rage inside one of the world's largest and most respected corporations, with a central figure, Kamb, who is portrayed in opposing legal filings as a charlatan and a victim - and may be both. Once again HP (Charts, Fortune 500) is accused of using shady and aggressive investigative tactics, including a high-pressure interrogation that reduced one of its own executives to tears. There's even an allegation - or more than an allegation, as we'll soon see - of corporate espionage. How did it unfold? Just 20 months after Fiorina's CES presentation, Kamb was fired. Then, along with six associates, all of whom had worked or consulted for HP, he was sued for $100 million by the tech giant. HP claimed that Kamb had betrayed the company and appropriated its trade secrets - and its money - to launch his own flat-panel-TV company, even as he was working on the TV project for HP. From its opening words the lawsuit seethed: "HP brings this action to redress a multimillion-dollar swindle perpetrated by several of its once-trusted high-level employees." The lengthy list of allegations included some that were straightforward - conspiracy and fraud - and others that seemed more a product of emotion than of reason: The $90 billion behemoth sued the 19-person startup for "unfair competition" and for racketeering, a charge originally designed for Mafia kingpins. The company even got personal, dredging up an adultery charge lodged against Kamb in his divorce. But that was nothing compared to the bombs Kamb dropped in a countersuit in January 2007. Kamb not only denied stealing trade secrets but also insisted that HP knew exactly what he had done with its money: He had used it in an operation that gathered "confidential information" on Dell, whose entry into printers had threatened HP's most lucrative line of business. As if that weren't enough, Kamb's suit accused HP of using fraudulent means to get his private phone records, the tactic known as pretexting. Kamb first accused HP of the misbehavior in August 2005, a year before the emergence of HP's high-profile scandal last year, in which investigators pretexted directors, employees, and reporters in an effort to smoke out a boardroom leaker. HP's legal papers flatly deny that the company pretexted Kamb. So incensed was HP by Kamb's counterclaim that it roared back into federal court and persuaded Judge Michael Schneider to issue an unusual ruling. He forced Kamb to withdraw his countersuit and refile it with the Dell-related allegations henceforth kept under seal, and he prohibited all parties from discussing any of that material with the press. The judge hasn't explained his rationale. But it seems reasonable to assume he wasn't going to countenance Kamb - a fired former employee accused of serious wrongdoing and desperate to save his own skin - using the media to even the odds against his better-armed opponent. As outlandish as Kamb's charges seem, however, independent evidence suggests that the wildest of his accusations - that HP sleuths obtained confidential information about Dell (Charts, Fortune 500) and that HP pretexted him - are true. Says Dell spokesman Bob Pearson, referring to the charges that HP spied on his company: "The more we look into it, the more concerned we become." HP's once pristine reputation was deeply tarnished by its pretexting scandal. But even at the darkest moments, CEO Mark Hurd, Fiorina's replacement, insisted that the sleazy machinations in the boardroom investigation were an anomaly. HP "has consistently earned recognition for our adherence to standards of ethics, privacy, and corporate responsibility," Hurd told Congress in sworn testimony in September 2006. He explained how a "proper" inquiry into boardroom leaks had "become a rogue investigation that violates our principles and values." The word he used to describe the fiasco was "aberration." That was the very term recently employed by Jon Hoak, the man hired by Hurd as chief ethics and compliance officer after the scandal. The imbroglio, Hoak told Bloomberg.com in April, was "an aberration rather than an indication of a culture problem." Hoak has been overhauling HP's investigative procedures, hiring new compliance staff, and readying a report for the California attorney general - due by the end of July - that will lay out the steps the company has taken to make sure such misbehavior doesn't happen again. HP declined to comment on the record, except for a statement the company submitted as this article was going to press (the full text can be found here.): "HP disputes a number of facts in this story, but court orders prevent us from commenting directly on them ... [The case] involves a former trusted HP executive who formed a competing business while working for HP. Our resulting lawsuit was brought based exclusively on documents recovered from company computers and from personal interviews. All of the alleged events involved occurred before HP took now well-documented steps to strengthen its investigative and ethical practices." Before we continue, let's be clear: Kamb's tangled tale is byzantine, and much of the evidence - even apart from that covered by the Dell-related gag order - remains secret. Many participants are leery of being interviewed. As a result, there are plenty of facts we simply do not know at this point. But an examination of 1,500 pages of court filings, exhibits, e-mails, and hearing transcripts, along with interviews with 20 lawyers or participants in Kamb's saga, reveal that once you strip out the invective, the two sides' versions of what happened are more similar than one might expect. Most important, the evidence at hand suggests that HP's tactics in its 2006 leak investigation may not have been such an aberration after all. HP hasn't explained why it has been so zealous in its pursuit of Kamb. But its fury, it appears, blinded it to the secrets he could spill. And a lawsuit intended to send a message about business ethics and the sanctity of proprietary information is revealing some embarrassing lapses by HP that otherwise might never have come to light. Pardon my past For a man who has been tenaciously trading legal blows with a much larger opponent, Karl Kamb comes across as anything but pugnacious. Indeed, sitting in his lawyer's conference room not far from his Las Vegas home, he admits that a year and a half into HP's suit against him, he's deeply depressed. "If they're trying to send a message," Kamb says of his former employer, "I've gotten it. I'm down on my knees, gasping for breath." Kamb's friends accuse him of having a melodramatic streak, he acknowledges. But behind his angst and caution (one of his lawyers was present to ensure that Kamb didn't run afoul of the judge's order), you can see glimpses of the garrulous and engaging man that friends describe. He still cracks the occasional joke, and he shows a talent for sound bites. His summary of the culture clash that ensued when Compaq, which employed him, was acquired by HP: "It's like pumping B-positive blood into an O-negative body." And his earnest explanations are periodically interrupted by megadecibel outbursts from AC/DC's "You Shook Me All Night Long" - the ringtone on the BlackBerry Pearl that hangs on a lanyard around his neck. |

Sponsors

|