Boeing bets the farmAfter years of losing to Airbus, Boeing is flying high. CFO James Bell tells Fortune's Geoff Colvin how the company did it.(Fortune Magazine) -- Times have never been headier for Boeing. It booked record orders in 2005 and 2006. Its new 787 is scheduled for rollout on July 8 - that's 7/8/07. The Dreamliner, as it is known, is living up to its name. It is the fastest-selling new airplane ever, with more than 500 ordered so far; it is sold out for years to come. For perspective, the hugely successful 747 has sold about 1,500 planes in its 39-year history. Meanwhile, the company's main competitor, Airbus, is somewhere near the seventh level of corporate hell, with its gargantuan A-380 years behind schedule and its competitor for the 787 still years from delivery. Little wonder that Boeing (Charts, Fortune 500) stock has recently hit new all-time highs.

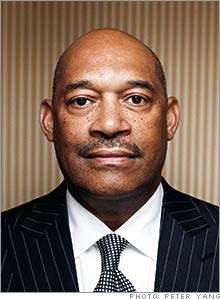

None of that means that being CFO is easy or even fun. James Bell, 58, got the job in 2003 after his predecessor was fired in a scandal involving the hiring of a government employee. Then CEO Harry Stonecipher was pushed out in 2005 after revelations of an affair with a subordinate. The board named Bell interim CEO (he remained CFO) until James McNerney from 3M (Charts, Fortune 500) arrived to take the top job. Today's problems, such as coping with runaway demand, are desirable worries. Nonetheless, such challenges can keep a CFO awake at night. Before an invited audience at the Time & Life Building in New York City, Bell talked recently with Fortune's Geoff Colvin about why Boeing made a different bet on the future than Airbus, how Bell copes with mammoth financial risks, today's overconfident young people, and much else. Here are edited excerpts. A lot of the new 787, including some of its most technologically advanced parts, is being made outside the U.S. Is Boeing -- and the U.S. -- in danger of losing its technological edge? There's always that concern when you see so much of a new product being developed outside the U.S., but other things have to be considered too. One is, What do you have to do to ensure market access around the world? The 787 has been the most successful launch in the history of civil aviation, so I think you have to have a balance. The technology, the design, the final assembly -- that's all being retained in the Boeing Co. Clearly, when you're building a new product that's having the success the 787 is having, you have to have some of the work done in the countries in which you're marketing the product. Where will Boeing be making airplanes in ten years? We have no plans to ever build a Boeing airplane -- to do the final assembly -- outside of where we've always done it, in our plants in Everett and Renton, Wash. More of the component parts are being built around the world and in other places in our country. How much of Boeing's growth will be in Asia? We've done really well in Asia, particularly in China. We're also spending a fair amount of time developing our presence in India, where we see a lot of growth in commercial air travel. These are large countries, and they have a need to move their people around, and they don't have the time to build infrastructure for travel by railway or roads. The easiest way to deal with that is through aviation. We are concentrated in those areas and expect to see a lot of growth from them. Airbus has bet on big airplanes -- the A-380 can seat 550 passengers. Boeing has bet on efficient airplanes. What makes you confident that you're right? It's not just efficient airplanes. We're also looking at smaller airplanes that can fly farther and join city pairs. Early on you built bigger planes because bigger planes could fly longer distances. With the advances in engine technology, that's no longer necessary. We think most people would like to fly point to point. When you build a large airplane, you have to employ the hub system because the large airplane can't access most of the airports. So you have to fly somewhere you don't really want to go to finally get on the airplane you want to get on. That's what has differentiated us on strategy and product offerings. The 787 can fly longer and has the same per-seat economics as large airplanes, so it's affordable. It's a good value proposition for our customers. If I wanted to buy a Dreamliner, what would it cost? About $200 million? A lot of things are taken into consideration, but it's a little less than that. Early on, when we were trying to entice customers, we were more flexible. Now we are more firm. If I were to order my 787 today, I wouldn't get it until 2013, right? Thereabouts -- maybe by 2012. We're sold out, and we don't intend yet to stretch out the production capabilities until we see what kind of capacity we have in the production chain. About a decade ago there was a rush of orders, and Boeing scaled up to meet them and then ran into problems. This time, the company has chosen not to ramp up production so fast. Do shareholders like to hear that or hate to hear that? What shareholders like to hear is that you're making money and creating value for them. Clearly, if you lose $3 billion by trying to ramp up and don't do it in a disciplined manner, which is what happened, shareholders will not be happy. We learned a lot in the last down cycle, where we cut our production in half and we were still able to operate profitably. So now that we are going up in production, we're using the same disciplined approach, making sure that we stay close to our supply chain. In 2001, Airbus had more net new orders for commercial aircraft than Boeing for the first time, and it was only in 2006 that Boeing won again (1,044 vs. 790). For years, Boeing has complained that Airbus is an unfair competitor because it gets government subsidies. Does its present distress undercut that argument? When you make a mistake, that's on you. I don't think it undermines the argument that Airbus needs assistance in order to compete with us. When we make a mistake, we also have to deal with it. If you were CFO of Airbus, what advice would you have for top management right now? Well, I don't know that I should offer any advice. We hate to see them in the position they're in. Having an injured competitor is really not healthy. But I would have looked at a lot of things relative to this question: "Should we [i.e., Airbus] continue to look into an investment [the A-380] that obviously doesn't seem to be paying off?" They can't operate their company like we can. We just have to deal with our shareholders. They have countries [Britain, France, Germany, and Spain] involved in their decision-making, and that makes it much more complicated to make the right business decisions in a timely way. I feel for my counterpart. He probably knows the right answer and probably is not able, because of the management structure, to actually implement it. When Boeing goes forward with a new program like the 787, you're essentially betting the company. How can a CFO ever get comfortable with that? If you're going to differentiate yourself, you have to be innovative. You have to dare to be great. But you can do things to mitigate the risk, and we've done that, particularly with the 787. We work very, very closely with our customers. We have customer knowledge of airlines all around the world, so when we decided on a midsize, mid-market airplane, we did that after very detailed consultation with our customers. That's what they thought they needed. After we made the midsize-airplane decision, we had to decide what kind of midsize. We originally thought about a Sonic Cruiser that would go 15% to 20% faster, but the speed wasn't throughput speed. You still had trouble at the front end getting through security and at the back end getting out of the airport. People weren't really willing to pay for the airplane speed, so that's what led us to the 787. For the first time we went to the third-party financing markets and asked, What kind of airplane would you be willing to finance, and finance more on the basis of the asset than on the customer's credit? Because as you know, the customer's credit in the airline industry isn't very good. They were willing to finance a product like the 787. So how I got comfortable was knowing we did all the right things upfront. We talked to all the right stakeholders and really utilized our detailed customer knowledge. Then we structured how we developed the product in a different way from before. Our subcontractors are bearing some of the risk of the development cost. That allows the CFO to feel a lot better about an investment -- if your supply team is feeling comfortable enough to invest their own money in it. Obviously I won't really be comfortable until we fly it, which we're targeted to do at the end of August or the beginning of September, and then put it into service next year. |

Sponsors

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||