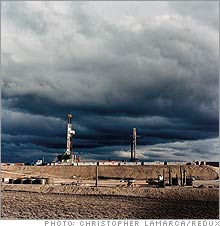

Wyoming's natural gas boom sees growing painsAn explosion of natural gas drilling in Wyoming has given the state a huge financial boost - and a new set of problems, says Fortune's Rebecca Clarren.(Fortune Magazine) -- On a windy Friday afternoon in Sublette County, Wyo., Ensign Rig No. 121 clanks and moans as it drives steel pipe 11,500 feet into the ground to capture natural gas. Just a few hundred yards away, framed against the stark blue sky, a half-dozen antelope bound across the sagebrush desert. Until recently the county's three million acres served mostly as a quiet and relatively isolated habitat for the herds of grazing animals. But at the moment it's hard to hear anything other than the hulking mechanism's steady percussion.

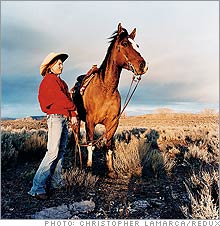

"I guess you could say it's like a gold rush out here," shouts 44-year-old supervisor Todd Arnold over the racket, with the 15-story derrick looming behind him. "Everything is going full bore right now. We keep all the components of this thing moving all the time - 24 hours a day, seven days a week." They can't afford not to. Arnold and his five-man crew are at the epicenter of the biggest boom ever to hit this part of cowboy country. His employer, Canadian natural gas giant EnCana, has drilled 374 new wells in Sublette in the past three years alone. A host of other multinational oil and gas companies, such as BP (Charts) and Exxon Mobil (Charts, Fortune 500), have rushed in as well. The promise of $25-an-hour starting pay for drillers has drawn thousands of men from as far away as Texas and Florida to this once-sleepy corner of western Wyoming. Arnold, who came from Utah, works up to 18 hours a day and makes more than $150,000 annually. A confluence of events in the global energy market brought the drillers here. In recent years Russia and Venezuela, both big natural gas suppliers, nationalized their fields, shutting off access to foreign companies. Simultaneously, natural gas production in the Gulf of Mexico - the source for 10 percent of American consumption - declined some 40 percent from 2000 to 2005, as easy-to-drill reserves were depleted and explorers had to move to deeper water. The tightening supply, combined with ever-increasing demand in the U.S., has helped lead to a quadrupling of the price of natural gas over the past decade. And that has created a new urgency to drill for Wyoming's "unconventional" gas - which sits not in easy pools above oil, but thousands of feet beneath the earth in pockets of sandstone and coal formations. "This is the frontier," says Fadel Gheit, a senior energy analyst with Oppenheimer & Co. "Wyoming has been underexplored and underexploited. Everybody and his brother want to go into this gas play and see how far they can push the envelope." Former Wyoming Congressman Dick Cheney also contributed to the gas grab. In 2001 the Vice President's much-argued-about Energy Task Force recommended that more public land throughout the Rocky Mountains be made available for gas development. In response, the Bureau of Land Management, the federal agency that issues drill permits to private companies for public land development, reduced environmental restrictions. In 2007 the BLM office in Wyoming plans to issue 4,545 new drilling permits, a 300 percent increase over 2002. There are already 26,900 wells in the state, the vast majority drilled in the past five years. Within the next decade gas companies plan to drill over 51,000 more. The 24 trillion cubic feet of recoverable natural gas beneath Wyoming is enough to power the entire country for one year. It is the second-largest proven natural gas reserve in the U.S., just behind Texas's. Already Wyoming's gas, which snakes out of the state in an expanding number of pipelines, provides fuel for much of Utah, Nevada, Kansas and Missouri, and accounts for an estimated 25 percent of California's consumption. The explosion in drilling activity has created a windfall for sparsely populated Wyoming (with 515,000 people, it has the smallest population of any state). Royalty payments from gas extraction created a nearly $2 billion budget surplus last year. To share the spoils, the legislature eliminated sales taxes on groceries and created scholarships for state colleges. The unemployment rate is down to 2.6 percent, one of the lowest in the country. According to the Bureau of Economic Analysis, from 2000 to 2006 per capita income in Wyoming rose 43 percent, the nation's largest increase. New Money Of course, sudden prosperity creates its own set of problems. Communities like Sublette County are scrambling to meet enormous infrastructure demands and manage the sudden influx of new workers. And environmental groups, hunters and ranchers worry about the impact on the land. There is also a danger that after gorging on easy profits for a few years, the state's economy could stagnate like those of so many natural-resource-rich nations after a commodities boom. Older Wyomingites are intimately familiar with how busts can follow flush times. The state went through a similar, if more modest, oil drilling craze during the 1970s. A popular bumper sticker in the mid-1980s read, OH GOD, PLEASE GIVE US ONE MORE BOOM. WE PROMISE NOT TO PISS THE NEXT ONE AWAY. So it's not surprising that back east in the capital city of Cheyenne, there is vigorous debate about how to spend the new riches. A state law requires that 40 percent of tax revenue from minerals flow into a trust fund. And the Republican-dominated legislature funneled an extra $40 million into the fund this year. But Democratic Governor Dave Freudenthal believes that's the wrong approach. He wants to give more money to places like Sublette County to fix highways, create affordable housing, and better monitor and regulate potential environmental impacts. "We should put that money to work instead of stuffing it in a sack," says Freudenthal. "We need to develop our natural resources in a way that preserves our quality of life in Wyoming." Sublette County sits in the Green River Basin, about 100 miles south of Yellowstone National Park and 75 miles south of the ski resort Jackson Hole. The area is abundantly rich in natural resources. In addition to fossil fuels, there are large deposits of uranium and soda ash, which is used to make glass. But the drillers have come to exploit two massive but previously undeveloped natural gas formations - the Jonah Field and the adjacent Pinedale Anticline, which together make up 29 percent of Wyoming's proven reserves. The local economy looks like a boomtown case study. In an area roughly the size of Connecticut, there isn't a single stoplight, but there are now five banks (up from two in 2004) and 11 real estate agencies. Since 2003 the county has built a senior center, a hockey rink and an indoor horse-riding area. A $17.2 million aquatic center - complete with two swimming pools, a helical slide and racquetball courts - is under construction. The school district has bought laptops for every fifth-grader, and teachers' base salaries have nearly doubled in four years. Rolling down a dirt road in his brand-new Dodge Durango, Sergeant Ty Gulbrandson heads out to patrol Sublette on Friday night. The number of calls the sheriff's department receives has more than doubled in the past five years, mostly because of the flood of men in the gasfields. Arrests have increased 94 percent since 2000, according to a 2006 county report. There's been a surge in the number of domestic-violence incidents and DUIs. There's also an influx of methamphetamine. "There's just so much demand for people and so much work out there," says Gulbrandson, 28, who lives with his wife and two young children in Big Piney, home to several "man camps," collections of trailers that house gasfield workers in five- by ten-foot rooms. "The meth is common, very common. A lot of them oilfield workers are great people and hard workers, but they work so many hours on these rigs that they tell me they use [meth] to keep them going. Once they're on it, it's hard to get off." Crime isn't the only problem that has swept in with the gas boom. High wages have lured away able-bodied people to the gasfields, leaving a shortage of workers for anything else. The manager of Pinedale's Sinclair gas station says she's been understaffed for three years. True Value Hardware closed last year in part because it couldn't find good affordable help. Restaurant and hotel owners, while grateful for the big business brought by the gas workers, complain it's hard to find employees. "Right now I'm in a pinch," says Wendi Schwartz, the straight-talking owner of Pinedale's Cafe on Pine, breathless as she runs back and forth to the kitchen, carrying heaping plates of pasta and chicken. "All these people come to work their gas jobs from Louisiana or Texas or what have you, they bring their families, but then there's such good money, the wives don't have to work. And a lot of the people that used to work in our industry are now working as receptionists at the office of the oil company." Although Sublette County businesses pay an average of $13 an hour, far above the federal minimum wage, the rising cost of living makes it hard for nondrillers to afford life here. Rental prices more than doubled in the past five years, according to state economic data, and the average home price jumped from $150,000 to $286,000. Schwartz and other local business owners have proposed ordinances that would mandate affordable housing, but the response from county officials is solidly unenthusiastic. "We resent regulation in Wyoming," says Bill Cramer, a Sublette County commissioner for 12 years. "We don't want to see any big bureaucracies. This is Republican country, and we believe in keeping government out of our lives as much as possible." So far the state hasn't shown any signs of trying to manage the unbridled growth. Cramer and other county officials point to the efforts by energy companies to reduce their environmental impact as evidence that additional government oversight is unnecessary. EnCana, for example, has lessened the effects on topsoil and root structures by setting its derricks on wooden mats rather than on the bare ground. EnCana and BP committed $24.5 million last year to enhance rangeland habitat in the area near their gasfield operations. But national and local environmental groups aren't convinced. They say the county's gasfields are important winter feeding grounds for animals that spend summers in Yellowstone, and since 2001 mule deer populations near Pinedale have declined by 45 percent, according to an industry- and government-funded study. In 2005, Governor Freudenthal established a trust fund that pays nonprofits and government organizations to create and improve wildlife habitat, but the fiscally conservative state legislature has appropriated less than half of what the governor requested. In the absence of long-term planning, some locals in Sublette worry about what will happen after the drillers are gone. As the sun lingers above a sandstone cliff, Tom Johnston, 75, and his granddaughter Laney, 13, walk across their Baylin' Wire Ranch outside Pinedale, past two original homestead log cabins, hay fields, and about 80 cows. A retired doctor, Johnston says ranching families can't afford to hire help. With escalating land values, he worries that his neighbors will sell to developers, draining away the cultural feel of this place. Laney stops to quiet her horse and as she looks out toward the mountains, she echoes her grandfather's concerns. "After I go to college and study science, I think I want to come back and do ranching because I love it here so much," she says, the sun glinting off the giant silver belt buckle she won at last year's 4-H show. "The money's nice, but we'll do anything for that gas, and what is going to happen once we lose all that? You're going to have problems where it doesn't look nice anymore, and you're going to lose the heritage of Wyoming. I worry about it a lot." From the June 11, 2007 issue

|

Sponsors

|