|

Green profits A brewery and bar in Salt Lake City wins over customers and boosts the bottom line with aggressive cuts in energy and water consumption.

SALT LAKE CITY (FSB Magazine) -- Downtown Salt Lake City is not the world's easiest place to operate a bar. Mormons dominate the population, and although some Mormons do consume alcohol, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has always frowned upon it. Also, the city's desert location means water is scarce and energy is expensive. Those challenges don't faze Jeff Polychronis. As the owner of Squatters Pub Brewery (squatters.com), located near the Mormon Tabernacle, Polychronis, 51, has found an ingenious path to the moral high ground and to cost savings -going green. Today his pub is lauded as one of the most environmentally friendly businesses in Utah.

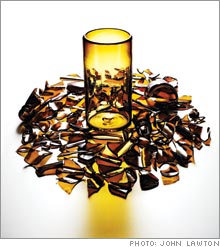

To get his Mormon customers to think well of his bar, Polychronis is trying to appeal to their concern for conservation. There exists a small but growing green constituency within the LDS church. Mormon environmentalists have argued in recent years that respect for the Creator requires respect for creation. This year church leaders are expected to endorse sustainable construction standards set by the U.S. Green Building Council. "We try to live in ways that protect and respect the land around us," says LDS spokesperson Paula Wright. While Polychronis has little doubt that his pub's green credentials soften its image among his Mormon customers, he is wary of being branded as an opportunist. "It's a tricky balance," he says. "I'll just say that we have found a way to prosper and be valued as good for the community." Last year Polychronis's company, which operates the downtown brewery as well as another one at the Salt Lake City airport, posted revenues of nearly $6 million, up 15% over the previous year, and a 30% increase in profits. Small-business owners rank rising energy costs as their fourth-biggest problem (after health-care insurance, liability insurance, and workers' compensation), according to a recent survey by the National Federation of Independent Business. In 2000, the last time that the NFIB conducted the survey, energy costs ranked tenth on the list. Says Polychronis: "Whether your employees are in an office running computers all day or cooking hamburgers in a kitchen, we can all figure out smarter ways to consume less energy." Polychronis started out skeptical that greening his brewery could improve Squatters' financial performance. Years ago one of his managers, James Soares, suggested that the pub recycle its used beer bottles into water glasses. Soares knew a local glass artist who could convert the bottles into funky glasses. But the math proved even funkier: Regular water glasses cost 47 cents apiece, while the recycled versions cost nearly $3. "Even I had to admit it was a bad idea," says Soares, 37. "But I am persistent." Soares came up with another idea: Why not sell the handblown, recycled glasses to customers at retail? It worked, and today Squatters sells the popular glasses for $14 a pop. Soares has since pushed Squatters toward other green initiatives: replacing plastic table covers with cloth, recycling paper products, and using reclaimed materials to remodel the brewery. The pub's three conventional urinals once guzzled an average 168,000 gallons of water a month. Soares suggested switching to new, waterless urinals, at a cost of $1,816. Nowadays water consumption is down to 97,240 gallons a month, which adds up to 850,000 fewer gallons each year. The result: In 2005, Squatters spent $1,479 on water, down 35% from the previous year. At that rate the urinals will pay for themselves in about three years. Squatters has also worked hard to reduce its electricity consumption. Two years ago the company's power bills were averaging $7,000 a quarter. But by replacing standard light fixtures with compact fluorescent bulbs and spending $6,500 on a new, high-temperature dishwasher, Squatters - even after adding a new walk-in freezer - has slashed electricity costs by 13%, to $6,099 a quarter. That translates to a 22-month payback. "All the investments we've made in the kitchen justify themselves by demanding less electricity," Polychronis says. Every penny counts. The brewery transports old cooking grease to a firm across town that converts the rancid goop into clean-burning biodiesel. Squatters buys the biodiesel back for $2 a gallon and uses it to run two vans whose diesel engines can burn it without needing alterations. Because conventional diesel prices now average about $3 a gallon, Squatters saves $480 a year (33%) in fuel costs. In total, green technology saved the company $7,050 last year. In 2004 the Recycling Coalition of Utah gave Squatters its Environmental Company of the Year award. "We're operating in the desert, and resources will be even more scarce ten years from now," says Soares. "Not only are we saving money today, but we have gotten a jump on all our competition, who will be forced to rethink how they operate." See the greenest office in America Homes going lean, mean and green Turning burgers and beers into big bucks |

|