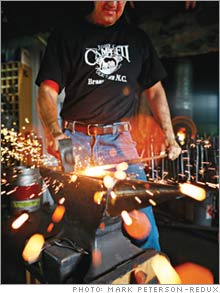

Offbeat SchoolsNew offerings for the weekend chef, blacksmith or covert operative.(FSB Magazine) -- Some people go back to school to study the great books. Others would rather learn how to throw a 14-inch knife, or hammer yellow-hot steel into semi-useful shapes or whip up a chocolate ganache that would make Julia Child sigh. There are hundreds of unusual schools in the U.S., teaching subjects increasingly diverse. Most are run by entrepreneurs trying to turn their knowledge and love of an obscure field into a business. Best of all, they don't require homework. Here, FSB enrolls in a few fall offerings around the country. Blacksmithing John C. Campbell Folk School; Brasstown, N.C.; folkschool.org

Standing in front of a glowing forge, sporting safety goggles and leather gloves, I grab one of the dozens of three-foot steel rods that line the wall of the Whitaker Blacksmith Shop and slide it into the fire. Within a minute the tip turns red, and I start pulling it out. My blacksmithing instructor, Paul Garrett, instructs otherwise. "Wait until it's bright yellow," he says. Steel turns red at about 1,000 degrees Fahrenheit, which seems hot enough for me but is apparently too cool for the metal to be malleable. A few seconds later the octagonal steel rod turns yellow, indicating that it's closer to 2,000 degrees. I remove it and rest it flat on an anvil, and Garrett hands me a large hammer. As I rotate the cool end, I strike down with the hammer and flatten the hot tip. Then I move the rod to the rounded edge of the anvil and keep hammering, watching the soft steel start to curl. Slowly my coathook - an unimpressive goal, but I'm a rank amateur - takes form. Garrett is the resident blacksmith of the John C. Campbell Folk School, in Brasstown, N.C. The school, founded in 1925, is a nonprofit geared toward teaching the art, culture and handicrafts of the Appalachian mountains. Its instructors offer more than 800 weekend and weeklong classes in subjects from knitting to fiddle playing to quilting. Last year some 6,000 students from 49 U.S. states and four other countries attended the school, whose tuition ranges from $235 to $485. A tall, solidly built man, Garrett, 43, trained for years as a blacksmith while working as a NASCAR mechanic for Sterlin Marlin. In addition to teaching, he owns a local firm, the Ironwood Forge, which sells household products such as towel racks and metal furniture. "Manipulating steel is the essence of what I do," he says. Scattered around the Whitaker studio are the simple tools of blacksmithing: anvils, chisels, hammers, grinders and tongs. The 12 students in my six-day course - Hot and Cold Forging With Ferrous and Nonferrous Metals, $412 - gingerly bend metal heated in coal-burning forges that can reach 2,500 degrees. "I love playing with fire," says one of the four women in my class, Stephanie Forbes, a 36-year-old zookeeper. Forbes lives in Seattle but grew up in nearby Andrews, N.C., where she frequently heard about the Folk School from other locals. Finally she decided to travel home and experience the place for herself. Forbes is making a decorative steel spoon with a copper handle, which for the moment sits with various works in progress lining a wooden table that runs the length of the building. Most of us are keeping our creations practical - lots of cooking utensils and fireplace tools - while a few of the more ambitious students are striving to create small sculptures. "Blacksmiths were the backbone of the community," says Garrett, pointing at a portrait of Francis Whitaker, a noted blacksmith after whom the studio is named, who died in 1999. "They repaired things. They made nails, bolts, hardware for wagons." After the six-day course, some of us will leave with at least one completed project. I, on the other hand, will go home with an appreciation for the art of blacksmithing and a piece of twisted metal that barely - if you're being generous - resembles a coathook. --Ron Stodghill Chocolate Saratoga Chocolates; Saratoga, Calif.; saratogachocolates.com Tempering melted chocolate is not the hard part. It involves smoothing the gooey liquid across a cool slab of marble with a spatula (chocolatier Mary Loomas tells us to "massage" it) until a kitchen thermometer shows that it has cooled to 89 degrees. Tempering ensures that the chocolate will harden at room temperature instead of staying soft and runny. The process seems pretty straightforward, until it's time to scoop the tempered chocolate back into a bowl. At that point I drizzle it everywhere. Fortunately cleanup is easy, and finger licking is allowed. In fact, chocolate gets in my mouth pretty much non-stop throughout my stint in the kitchen at Saratoga Chocolates, a tiny storefront surrounded by antique shops and upscale restaurants in the small town of Saratoga, Calif., 45 miles south of San Francisco. I've come for Loomas's course on making truffles from scratch. A former comptroller at Intel, Loomas, now 42, took up chocolate making as a hobby four years ago. She signed up for a three-month class and then a week of intensive study at the prestigious �cole Chocolat in Tain l'Hermitage, France, which is run by leading chocolate maker Valrhona and has trained some of the top pastry chefs in the world. As soon as she returned home, she applied her MBA to writing a business plan. Saratoga Chocolates opened its doors in November 2005. "I loved working in high tech, but now I can't wait to get to work in the morning," she says. "I get giddy about what I get to do every day. Of course, that might be all the chocolate I'm eating." She projects revenues of $200,000 for her first year, 30 percent from her wholesale business at local hotels, spas and gourmet food boutiques, including Berkeley's renowned Pasta Shop. The rest comes from retail and corporate customers, including a Silicon Valley company that recently bought 350 boxes of truffles to hand out at a trade show. From Thanksgiving to Valentine's Day, Loomas and her five employees concentrate on candy. The rest of the year she also teaches two to four classes a month for as many as six people at a time. The basic course covers truffle making: melting, tempering, making ganache and dipping. For those who can't get enough (and who can?), she also offers Basics II: molded chocolates, filled chocolates and chocolate-covered fruit. Each costs $100, with a 10 percent discount for enrolling in both. Everyone leaves with detailed instructions for chocolate making at home. Playing chocolatier is easier than I expected. The only equipment necessary is a spatula, a microwave, bowls and measuring cups, an accurate thermometer and a cool surface. (We use an infrared chef's thermometer at a giant marble-topped kitchen island, but at home, Loomas says, an ordinary kitchen thermometer and an upside-down cookie sheet will do.) The hardest part is achieving the proper temperature at each step, but even there beginners can make multiple attempts: As long as the chocolate isn't burned, you can heat it back up and start over. Loomas's joy is contagious. At one point she smears chocolate on her chin to demonstrate how the chocolate should, at that stage, be slightly cooler than skin temperature. Later she whistles like an incoming mortar round as we dunk balls of ganache - the chocolate/cream/butter mix inside a truffle - into the tempered chocolate. In between, she tells us how to melt chocolate in the microwave (in small pieces, in one-minute increments, at half power), why a single drop of water can ruin an entire batch of candy (it makes the melted chocolate curdle like sour milk), and how to make Earl Grey truffles (steep a tea bag in the cream used to make the ganache). Another lesson she hammers home is the importance of quality ingredients, bought from local small businesses wherever possible. The dark chocolate scenting the air and staining my chef's apron is a mix of Bay Area premium brands - bittersweet Scharffen Berger (70 percent cocoa) and dark E. Guittard (72 percent) - and the butter and cream come from happy cows on nearby farms. At the end of the evening we drizzle our creations with thin stripes of milk chocolate and tuck them into little paper candy cups. Lined up in a box, my 40 truffles look surprisingly professional, so much so that I hate to spoil the effect by eating any. I pop one in my mouth anyway. It tastes surprisingly professional. I think I've solved my holiday gift problem this year. --Fawn Fitter Knife throwing The Great Throwdini; Freeport, N.Y.; knifethrower.com Blame the warm weather. The knife sticks in my sweaty palm, and as soon as I throw it, I know it's going to miss the five-foot board - by a lot. Instead it hits the lovely Long Island house of the Great Throwdini (a.k.a. David Adamovich), where it leaves a black mark on the siding and bounces to the ground. A long moment passes before Adamovich speaks. "Aim lower," he says, a tomahawk in his hands. "And follow through." Ten years ago Adamovich, now 59, retired as a physiology professor and bought a billiard hall on Long Island. One day a regular came in with an eight-inch throwing knife. The two went outside and started throwing, and Adamovich learned he was a natural - his first toss struck the tree perfectly, blade parallel to the ground. "I said, 'I can do this,' " he recalls. Nine months later, after setting up a practice range on his deck and recruiting the New England divisional champion as a partner, he reached the finals of the International Knife Throwing Alliance's World Championship in Las Vegas. Adamovich now holds six world records and performs about 20 solo shows a year, throwing knives in the direction of scantily clad assistants, known in the business as target girls. He has performed on Broadway, at corporate events and weddings, and on TV shows such as Late Show With David Letterman and ESPN's Cold Pizza. In April he threw 72 knives around a human target in 60 seconds, more than anyone else in the sport's history. He makes around $100,000 a year for his knife-related ventures - not enough for him to sell the pool hall yet. For $75 an hour Adamovich also offers private lessons. (If you don't want to make the trip to Long Island, he sells an instructional DVD.) My friend Amy and I arrive to find a table set up on his deck, with six sets of different-sized throwing knives inside a case lined with red velvet. Along the perimeter of the deck are all the tools that beginners unfortunately aren't allowed to touch, including the Wheel of Death, a rotating throwing board that target girls get strapped onto during performances. The knives, which look more like knife shapes cut from cheap stainless steel, are surprisingly heavy but blunt. Adamovich begins by running a blade down the center of my palm: Unless you're a target girl with a piece of steel rushing toward you at 30 miles an hour, the knives aren't sharp enough to puncture the skin. (In ten years, using knives of all shapes, sizes and degrees of sharpness, Adamovich has never drawn blood.) The biggest threat for beginners is getting bruised by an errant throw bouncing off the wall. "That can hurt," he says. Throwing a knife uses the same motion as the Atlanta Braves' tomahawk chop. If you're right-handed, you drop the knife back near your right ear, then bring it forward, moving your arm in a straight line toward your right foot. Both Amy and I make the mistake of flicking our wrists, which causes the knives to spin too fast and hit the board at awkward angles. The first few throws don't stick and clatter to the deck like dropped dinnerware. Eventually the knives start to penetrate, though, and for the next 90 minutes Amy and I work our way farther out from the board. Adamovich lets us try tomahawks, which require more patience and strength because of their top-heavy heads. He straps Amy onto the Wheel of Death, where he hurls a few knives at her to gauge how much she flinches. (Surprisingly, not much.) I stick to tossing. I've become addicted to the rhythm of the "peel and throw" method. Knives stacked in my left hand, I peel them off one by one and throw, eyes never leaving the spot I want to hit. The repetition becomes relaxing, and Adamovich tells me that many of the students he teaches each year are doctors, who claim that the sport relieves stress. I'm just glad I hit the house of the Great Throwdini only once. --Maggie Overfelt Other Fun Schools --Mina Kimes COVERT OPERATIONS covertops.com; 800-644-7382 Discover your inner James Bond at Incredible Adventures' three-day class ($3,795), where you'll learn evasive-driving maneuvers, self-defense techniques, and weapons tactics. Many of the instructors have served in U.S. Special Forces teams. The highlight? Rescuing a "kidnapped" student in a live-fire (meaning paintball) assault. BULLFIGHTING bullfightschool.com; 619-709-0664 The California Academy of Tauromaquia, in San Diego, is the first bullfighting school in the U.S. and is staffed by established matadors. The initial training involves wheelbarrows with horns on them, but the final exam is you against a yearling heifer (which lives to fight again). A five-day package, including a field trip to Mexico, costs $2,000. DOGSLEDDING alaskadogsledding.com; 877-923-2419 Eighteen-time Iditarod finisher - and inductee into the Iditarod Hall of Fame - Jerry Austin has been running dogsled trips since 1976. Austin's Alaska Adventures, based in St. Michael, Alaska, offers a five-day mushing odyssey through the icy tundra that includes dogsledding, snowshoeing and hiking ($1,995). To write a note to the editor about this article, click here. |

|