|

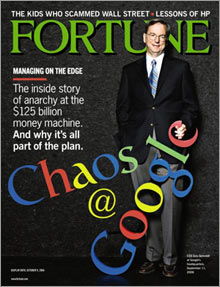

What is Google's second act? Google has exceeded everyone's expectations despite its laid-back culture and chaotic business manner, but many are left wondering what Google will do for an encore.

(Fortune Magazine) -- Two years after going public, Google's stock is up more than fourfold, and it's so profitable that despite helter-skelter spending on everything from mammoth data centers to worldwide sales and engineering offices, Google is generating more than $800 million in cash each quarter. In the process, Google is thrashing the competition - in market share, deals won, buzz - notably Yahoo (Charts) and Microsoft (Charts) It's also cozying up to a growing list of heavyweights you'd think would be warier, including News Corp (Charts)., Viacom (Charts), and ad-agency giant WPP (Charts).

(This is an excerpt from a story that appeared in the October 2 issue of Fortune. Read the full story.) If Google's engine is running fast, then naturally it's also running hot. That sheds light on all kinds of blunders which Google (Charts) likes to explain away as its Googley approach to business. (Googley being a cloying description these people actually say out loud. Frequently.) The company is figuring things out as it goes, and not quite as effectively as you'd expect from its stellar financial results. Its new products haven't made nearly the splash that its original search engine did. Critics have mocked its self-righteous "Don't be evil" motto when, for example, Google decided to scan copyrighted books for its book search index. Even Google's rocket-ship stock price has been grounded. After a run from $85 in August 2004 to $475 last January, it has puttered around $400 for most of the year. Says Benjamin Schachter, an analyst with UBS: "Investors are saying, 'Enough of what you're going to do. What does it do to the numbers?' " A one-trick pony? What concerns investors is whether Google can come up with a second act. There's nothing to suggest that its growth engine - ad-supported search - is in trouble. But it's clear from Google's tentative lurches into new forms of advertising and its spaghetti method of product development (toss against wall, see if sticks) that the company is searching for ways to grow beyond that well-run core. It's the reason, for example, that Google requires all engineers to spend 20 percent of their time pursuing their own ideas. For all its new products - depending on how you count, Google has released at least 83 full-fledged and test-stage products - none has altered the Web landscape the way Google.com did. Additions like the photo site Picasa, Google Finance, and Google Blog Search belie Google's ardent claim that it doesn't do me-too products. Often new services lack a stunningly obvious feature. Users of Google's new online spreadsheet program, for instance, initially couldn't print their documents. The calendar product doesn't allow for synchronization with Microsoft Outlook, a necessity for corporate users. Other major initiatives like Gmail, instant-messaging, and online mapping, while nifty, haven't come close to dislodging the market leaders. Much-hyped projects like the comparison-shopping site Froogle (nearly four years in beta and counting) and Google's video-sharing site have been far less popular than the competition. One of Google's biggest misses is its social-networking site, Orkut, which is a hit only in Brazil and -- as Marissa Mayer, Google's 31-year-old vice president of search products and user experience, says with an impressively straight face -- is "very strong in Iran." Sometimes promising new products are buried so deep within Google's sites that users can't find them. "You can only keep so many things in your head," acknowledges CEO Eric Schmidt. "Even if you're the No. 1 Google supporter, you cannot remember all the products we have." Neat toys are about more than creating Web pages on which Google can slap ads. Google Earth, the ubiquitous cable-news prop and workplace time waster that lets users view incredibly detailed geographic photos from around the world, has been downloaded more than 100 million times, and embedded in each download is a request from Google to place a toolbar, a Web gadget that includes a search box, permanently on a user's Web browser. That seemingly innocuous query is a gold mine for Google, because the ever present box increases the likelihood users will search on Google. The more people search on Google, the greater the chances someone will click on an advertiser's ads. Branching out This virtuous cycle of more users conducting more searches benefiting more advertisers is precisely what makes Google so irresistible to business partners -- even those who feel threatened by it. Martin Sorrell, the chief executive of ad agency holding company WPP, has been outspoken in his fear that Google could obviate companies like his. (Automated ad auctions entail less overhead than armies of schmoozing ad executives, goes the argument.) He titled a section of his latest annual report "Google: Friend or Foe?" In an interview, he suggests the short answer: "The bigger and more successful you get, the more people want to bring you down." But it's not that simple. WPP, Sorrell notes, is Google's third-largest customer, measured by the amount of advertising it purchases on Google for its clients. Working with Google and grumbling about it is quite in fashion. Viacom's MTV recently signed a deal for Google to distribute its videos to the Web publishers in Google's AdSense network, which lets the publishers run ads supplied by Google's advertisers. Comcast, which has been Google's ideological opponent in an acrimonious legislative battle over government regulation of Net access, is particularly pleased with the revenue it gets from having Google power the search results on its Comcast.net home page for broadband users. Google has begun to show how it plans to use its new data centers for advertising services that go beyond search. Brokering video ads for MTV is new terrain, as are the graphical display ads Google plans to sell for MySpace. The company is engaged in an 18-month-old experiment to auction text and graphical ads for newspapers and magazines. It's also in the process of integrating its biggest acquisition to date, a radio-advertising company called dMarc Broadcasting, which Google bought in January for $102 million in cash plus a potential performance-based payout of more than $1 billion. dMarc automates the process for delivering radio ads to about 10 percent of the country's 10,000 stations. By merging dMarc into Google's AdWords, Google's online system for auctioning search terms, it will offer its advertisers -- who so far hawk their wares in 75 words or less of written text -- the ability to deploy radio ads as well. With so many moving parts, it's natural to wonder if Google is truly a company for the ages -- or whether it's the next fast-moving, arrogant, one-hit wonder. To believe that Google will find its second act, you have to accept the hubris and the chaos, and that the brainiacs who got lucky once will do so again. (This is an excerpt from a longer story that appeared in the October 2 issue of Fortune. Read the full story.) |

|