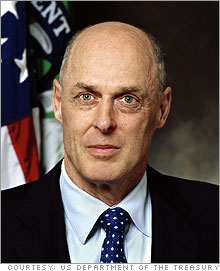

Paulson sees more bad news aheadBut the Treasury Secretary tells Fortune's Nina Easton that the economy is strong enough to withstand the volatility.WASHINGTON (Fortune) -- Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson predicts that the "current strained situation" in the markets "will take time to play out, and more difficult news will come to light. Some investors will take losses, some organizations will fail," he says in remarks that will appear in the forthcoming issue of Fortune. But, he stresses, global economic fundamentals remain healthy, providing a solid base for financial markets to continue to adjust. "The overall economy and the market are healthy enough to absorb all this," he notes.

This is the kind of carefully calibrated observation that has become the hallmark of Paulson's public remarks during a volatile summer. How to acknowledge bad news without feeding it is at the crux of a communications dilemma for the Bush administration. It's not an easy balance. Attempting to cheerlead a squirrely market is a dangerous enterprise, akin to "catching a falling knife" says former White House economics adviser Lawrence B. Lindsey, because "you risk looking impotent" if the market continues to fall. But saying nothing can carry its own risks, too, if the markets interpret that invisibility as a sign of no-confidence. And what administration officials say publicly can have almost as much impact on markets as what the Federal Reserve Board decides behind closed doors. That's a lesson that Treasury Secretaries sometimes learn the hard way. In the spring of 2003, ABC News' George Stephanopoulos asked Treasury Secretary John Snow a question about the relationship between the value of the U.S. dollar and American exports. The former railroad executive offered what he thought, according to aides, was a standard Econ 101 response: "Well you know, when the dollar is at a lower level, it helps exports. And I think that exports are getting stronger as a result, yes." Traders took Snow's remark as a statement of intent, which contributed to turmoil in the currency markets and helped send the dollar to a four-year low against the euro. Snow's verbal blunder was the kind of mistake Bush Administration officials are keen to avoid as they seek to calm turbulent markets. In an interview with the Wall Street Journal this week, Paulson acknowledged what everyone was thinking, that the turmoil "will extract a penalty on the growth rate" of the U.S. economy. But he tempered that cold water with warm words of reassurance that "the economy and the markets are strong enough to absorb the losses" without bringing on a recession. In his essay in Fortune, Paulson noted: "The lesson here is not new - in a long period of economic expansion and benign markets, there is a temptation to give way to excesses. This has been a wake-up call. It's a reminder that all participants need to completely understand the risks they take and be vigilant." During the worst of this month's market turmoil so far -- Aug. 9 and 10 -- Paulson kept a low profile, but was working behind the scenes to craft the government's response. Behind closed doors, he gathered market intelligence from Wall Street sources he knew from his long tenure at Goldman Sachs (Charts, Fortune 500). In between, he conferred regularly with Fed chairman Ben Bernanke, with whom he has developed a close working relationship (Paulson marked his one-year anniversary in the job a month ago; for Bernanke it was six months ago), and with New York Fed president Timothy Geithner, who had worked inside the Treasury building as undersecretary for international affairs during the last years of the Clinton Administration. He also fielded calls from Capitol Hill. When the Fed chose to communicate with the markets, it was in a kind of code -- choosing to inject liquidity in an unusual and specific way by entering the mortgage securities markets. Former Fed vice chairman Alice Rivlin characterized the move as "symbolic," since the credit market's troubles were rooted in housing woes. Added Lindsey, who also served on the Fed in the 90s: "What the Fed did was exemplary and textbook. And it sent a very important signal." No one expects the Fed to elaborate on its intentions. But Administration officials -- from the President on down -- are routinely called upon to comment on market turns. So communications aides have been forced to school themselves in the art of what to say -- and what not to say. In recent years, Treasury aides have trekked to financial exchange floors in New York City, Chicago, Tokyo, Shanghai and elsewhere to watch the volatile emotions of traders in action, an attempt to better understand the links between Administration comments and unintended market reactions. "The most valuable time we spent was talking to traders," said Tony Fratto, now deputy press secretary at the White House. "They don't care about what the policy is. They care about whether the market is going to move up or down in the next five minutes. Their lives are broken into 30-second increments." Paulson's August strategy is to make the same number of public appearances as he would during a normal market period. "That, in and of itself, is a sign of normalcy," says Michele Davis, Treasury's assistant secretary for public affairs and director of policy planning. On Aug. 1, while in Beijing, reporters asked Paulson to reflect on turbulence that had infected the markets over the previous 24 hours. He carefully repeated previous statements, to indicate a steady course. "Let me be pretty clear about what I've said before," the Treasury Secretary said. "When I said the housing market was at or near the bottom, I also have said that I thought this would not resolve itself any time soon, and that it would take a reasonably good period of time for the sub-prime issues to move through the economy as mortgages reset. But I said as an economic matter I believe this was largely contained because we have a diverse and healthy economy." He repeated the same message a week later. Still, the markets continued to reel. So the administration was taking a calculated risk when George W. Bush -- a President who has raised verbal gaffery to an art -- fulfilled a long-standing commitment to sit down with a group of economic writers for a free-wheeling discussion on the afternoon of Aug. 8, with markets suffering an unpredictable case of nerves. As the nearly hour-long session came to a close, White House aides could breathe a sigh of relief. While Bush botched the name of China's vice premier (conflating Wu Yi into "Wi"), the Harvard-MBA President skillfully fielded economic questions: The "underlying underpinnings of our economy are strong," "liquidity will provide the capacity for our system to adjust," "my hope is that the market..will be able to yield a soft landing." No harm, no foul. But the President's steady performance wasn't enough to soothe fear-stricken markets, which gyrated sickeningly over the course of the following two days, prompting the Fed to start injecting tens of billions of dollars into the financial system to ease fears of a credit crunch. By then, Administration officials had gone into radio silence, aware that anything they said might spook the markets. While some analysts criticize Administration officials for trying to up-talk a nervous market in the days leading up to that episode, Rivlin credits them with playing their appropriate roles. "That's what presidents have to say," she noted, adding that Paulson has consistently chosen "calming" words. The Bush team has always prided itself on "message discipline" in politics. When it comes to the unpredictable twists and turns of financial markets, that will be more of a struggle. For right now, though, Bush Inc. is attempting to operate under its own medical injunction: "First, do no harm." |

Sponsors

| |||||||||||||