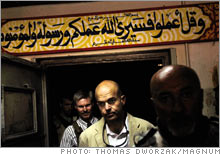

In Iraq, one man's Mission ImpossibleA former Silicon Valley exec turned Pentagon boss wants to put Iraq back to work. But he's run into many roadblocks - including his own government.(Fortune Magazine) -- It's 120 degrees in the heart of the Sunni "triangle of death," and a few dozen U.S. soldiers in full combat gear ready their weapons outside a warehouse. The bombed-out buildings nearby, the cracked pavement underfoot, the Apache helicopters circling overhead: B-reel for a war gone sour. A man in a dark suit and gold tie yells in Arabic for a worker in stained coveralls to open the rusted metal doors. As a handful of soldiers rush in and take defensive positions, an American wearing hiking boots, khakis, and a blazer ushers his entourage inside.

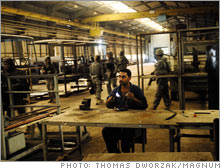

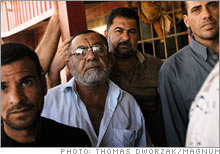

"Most people back home are shocked," the American says, peeling off his wraparound Oakleys, "shocked when I show them an image of an Iraqi working at a modern factory." The dark, cavernous warehouse is an assembly plant of the State Co. for Automotive Industry near the ancient town of Iskandariya, about 25 miles south of Baghdad. Most of the 50 or so workers in sight are welding or screwing or hammering pieces of metal on windowless armored buses. Few pay attention to the American civilians wearing full body armor or the phalanx of soldiers there to protect them. The not-so-quiet American is Paul Brinkley, a fast-talking 40-year-old deputy undersecretary of defense. The onetime Silicon Valley executive has spent the past year trying to reopen parts of what he calls "Iraq Inc." - the nearly 200 state-owned factories that once manufactured everything from toilets to toothpaste to tractors. This bus factory is his favorite success story. "When we first came here last year," he says, "it was a ghost town. Everyone was just sitting around drinking tea." One of the little-known consequences of the American-led regime change four years ago was that most of the country's half-million industrial workers lost their jobs when the Baathist government, which had run the factories, collapsed. American administrators, who believed the Soviet-style system was antiquated, inefficient, and, well, socialist, had no interest in restarting the factories. Pure, unvarnished, American-style capitalism was the answer. But while waiting for Adam Smith, says Sabah al Khafaji, the director-general of the bus factory, some of his former workers joined the insurgency. "At least they paid," he says through a translator. Brinkley has another idea. A balding systems engineer with four patents to his name and backslapping Texas charm, he says his strategy isn't rocket science: If you have a decent job, you're less likely to plant a roadside bomb. But the implementation of that strategy has proved far more complicated and controversial than anyone expected. Money to get the factories restarted has been hard to come by. Finding buyers for the goods in the U.S. has been even harder (only one company, a small Memphis retailer, has signed on so far). And that's on top of the Herculean challenges of doing business in a war zone where electricity is erratic, supplies are scarce, and employees can get blown up on the way to work. Even people in his own government snipe at him. Brinkley has been called a "Stalinist" hell-bent on fixing a broken system and a "well-intentioned guy on a fool's errand." Two members of his own team, relieved of duty by Brinkley in late July, have called the yearlong effort a failure. In a 12-page memo submitted to the Defense Department's inspector general, they also accused Brinkley of erratic behavior, public drunkenness, mismanagement, sexual harassment, and wasting taxpayer dollars - charges Brinkley vehemently denies. While the attacks have clearly hurt Brinkley, he admits he's disappointed with his pace. Only 16 factories have been restarted, creating about 5,000 jobs. "This isn't going well," he says. Those 16 include a leather factory in Baghdad, a clothing factory in Najaf, a plant in Ramadi that makes porcelain sinks, a flour mill near Tikrit, and the bus facility. All are operating on a much smaller scale than in Saddam's day and in most cases paying lower wages. In the 1980s the bus factory produced six to ten vehicles a day. "Last month we built six," says al Khafaji, adding that he can employ only 1,000 of his former 4,000-man workforce. "The free market has been tough on us." To survive he has had to diversify. Thanks in large part to Brinkley's Task Force to Improve Business and Stability Operations, al Khafaji's factory now builds towers for refineries, fabricates steel to repair bridges, and, under a $6 million contract with the U.S., assembles modular buildings and produces armored buses for the Iraqi military. Of course, no one will confuse this place with a Toyota plant in Kentucky. The workers wear sandals, the machinery is from the 1970s, and most of the welding is still done by hand. The buses themselves probably wouldn't stand up to Western quality standards. Inside one of the coaches the screws don't seem fully secured, the welding appears uneven, and the upholstery doesn't fit. "We are in the Stone Age," says one worker, putting down his Russian-made drill. He refuses to give his name for fear of being singled out by the insurgents: "No good can come from talking to Americans." Brinkley was there that day to hand al Khafaji a check for $1.5 million - or at least an oversized ceremonial version of one - so that he can buy new machinery. "What's the alternative?" Brinkley asks. "We've been at this for four years. A free market hasn't emerged. You've got over 50% unemployment. Can't we take it as table stakes that mass unemployment creates social unrest? If you're not going to try to put everybody back to work anyway you can, what do you do? Just pull out and leave them unemployed and angry?" "This is the real deal," a young sergeant tells Brinkley's group a few days later. "In the event of a likely explosion, know where the first-aid kits are. Also make sure your door is bolted shut, as sometimes they like to open the doors and throw a grenade in." It's a speech Brinkley has heard countless times. We're at the airport in Mosul, Iraq's third-largest city, on our way to the State Co. for Drugs & Medical Supplies. It's an hour away, down some of the most dangerous streets in the country. As the nine-vehicle convoy winds in and out of traffic, the drivers of the armored Humvees swerve to avoid anything remotely resembling a bomb. "Left, left!" the sergeant yells. "That's where they hid an IED last week." The pharmaceutical factory sits atop a small hill, ten minutes from the nearest building. Rubble is all that's left of the company's saline production line, which coalition forces leveled in 2003. But inside is a modern drugmaking facility that could just as easily be in Maryland. The workers wear crisp white lab coats. Chemotherapy drugs pour out of state-of-the-art Italian machines. Tubes of hydrocortisone cream roll off conveyer belts. "We'll be ready for FDA inspection soon," the factory's director-general promises, adding that Iraqis have been spending $100 or more on drugs imported from Jordan that he now makes for less than $2. Modern factories were once the hallmark of Saddam Hussein's regime. Thanks to decades of oil wealth, Iraq was the most industrialized country in the Arab world. Government jobs - in factories, with the army, at universities - were guaranteed for life. Paychecks weren't high, but the cost of living was artificially low. Electricity was free, as was a college education and health care. Gas cost less than a nickel a gallon. Every household received monthly food rations. Things started going downhill when Saddam invaded Kuwait in the early 1990s. The country became isolated, debt-ridden, and so weakened by UN sanctions that it couldn't import many of the raw materials it needed. Iraqis blamed the worsening conditions on Saddam but assumed that once he was gone, the country would become even richer than before. So did the Americans. The Bush administration spent months before the war debating how best to remake Iraq's economy. The resulting plan was detailed in a 101-page document that called for the privatization of state-owned enterprises, the establishment of a "world class" stock exchange, and the imposition of a modern income-tax system. When he got to Baghdad in 2003, Paul Bremer, head of the Coalition Provisional Authority, wasted little time. He signed orders lowering Iraq's corporate tax rate from roughly 40% to a flat 15%, allowing foreign companies to own 100% of Iraqi assets other than oil, and welcoming foreign banks under the same favorable terms. All that remained of Saddam's economic policies was a law restricting trade unions and collective bargaining. So when Timothy Carney, the first U.S. advisor to Iraq's Ministry of Industry and Minerals, proposed reopening many of the country's factories, he was quickly shot down. Bremer's team believed in economic "shock therapy," making painful adjustments rapidly in the aftermath of a seismic social disruption like war. The population would be so stunned, so preoccupied with the daily pressures of survival, or so the theory goes, that it would be unable to resist. Mass unemployment? It didn't matter, Bremer's people said, since the CPA had agreed to pay workers about 40% of their former salaries - enough to keep them from starving but not enough so they'd stay on the dole. The Bremer plan produced shock but little therapy. Privatization, it turned out, probably wasn't legal; the CPA's lawyers thought it might violate international law if the U.S. facilitated the sale of the Iraqi-owned enterprises. The elimination of subsidies and the seizure of bank balances left businesses with no money to buy raw materials. Through successive Iraqi governments, most state-owned factories remained shuttered. Green beans is one of the few places in the Baghdad embassy compound to conduct a business meeting outside your office. (Another is by the pool behind what was Saddam's Republican Palace.) It's a Starbucks wannabe, with $5 mocha frappes and a portable boombox that plays everything from Indian pop to Johnny Cash - and, yes, it sells a soundtrack. Brinkley, whose team was allocated only a six- by 12-foot office by the embassy, conducts much of his business here. Sitting at a table one afternoon in August, sipping a cup of coffee - his fourth of the day - he was conducting a meeting about restarting the agricultural sector. He hadn't slept much the night before and was cranky. (A night owl, Brinkley will often head to the gym at 10 p.m., then go back to work until 2 a.m.) Back-to-back meetings hadn't helped. "Yesterday I was at a clothing factory in Mosul," Brinkley says, "and we were thinking, one way these guys could make a killing is if they could manufacture clothes out of organic cotton. And since organic cotton needs a field that hasn't had pesticides in three or four years, it would seem Iraq would be a perfect place to start doing that. What would it take to get the cotton industry going again?" The question doesn't sit well with Ronald Curtis, the economic development and agricultural policy advisor in Baghdad for the U.S. Agency for International Development. "I need to make it clear to you," Curtis says from across the table, "that I cannot work with any state-owned industry." "That's not what I'm asking," Brinkley snaps back. "I'm trying to create a market for agriculture. You shouldn't care whether the company buying the cotton is state owned or privately owned, as long as it pays a fair price." The meeting didn't last long. "Last summer these fights were even worse," Brinkley fumes on the way back to his office. Before joining the Defense Department three years ago, Brinkley was a senior vice president at JDS Uniphase (Charts), an optical-technology manufacturer near San Jose. There he ran the logistics, customer service, and information technology departments and helped move much of the company's manufacturing abroad. The Pentagon recruited Brinkley to help modernize the military supply chain. But he was soon analyzing its business and accounting practices - no small task, considering there are 2,000 business systems for processing financial transactions alone. His initial mission to Iraq last May was to simplify contracting to give Iraqi firms a better chance of providing goods and services to the U.S. military. While in Baghdad, Lt. Gen. Peter Chiarelli, then a top U.S. commander in Iraq, asked him to inspect the bus factory in Iskandariya. He said his men kept catching former factory workers setting roadside bombs. "So we put our team in a convoy and drove through extremely rough neighborhoods," Brinkley says. "People were standing on the side of the road staring daggers at us." When he saw that the factory was shut down, he asked why everybody was out of work. "Those are state-owned industries," he was told later. "If you restart them, you're going to be employing insurgents." When he got back to Washington, Brinkley tried to convince his superiors that by restarting Iraq's industrial base he could make a dent in Iraq's unemployment rate. He thought of it as turning around a company. By the end of last summer he had put together a team of turnaround experts, manufacturing consultants, and forensic accountants. They concluded there were at least 20 factories worth reopening. For less than $200 million, Brinkley argued, he could reopen these factories and put thousands of Iraqis back to work. But there were no Pentagon funds earmarked for such a project. Ditto at the State Department. And Iraqi law, thanks to CPA regulations still in effect, prevents investment in state-owned factories. It took more than seven months to get the Ministry of Finance to consider granting low-interest loans. It took even longer to get $50 million appropriated by the U.S. Congress. And outside investors weren't interested. Brinkley took about 100 executives to Iraq, at a cost of roughly $1 million; not one invested. "The big issue is security," says Joseph Saoud, an executive at Cummins, a U.S. engine manufacturer, who visited the bus factory in Iskandariya. The State Department continued to put up roadblocks. It asked the CIA to investigate the link between unemployment and attacks on U.S. forces. (The agency found no correlation.) The embassy in Baghdad even commissioned a Rand study to rebut Brinkley. It concluded, "Trying to give these enterprises a new lease on life will make Iraqis poorer without reducing the violence." Brinkley wasn't prepared for the sniping. "I thought to myself," he says, "Why are we even having this conversation?' But we did. And we still do. There are still people who will look you in the eye and tell you the problems in Iraq have nothing to do with economics - that it's strictly sectarian divisions and a desire of people to exact revenge. I find that argument absurd." Not far from Babylon, Brinkley and his deputies sit around a table with another oversized check, this one for $2 million. We're at the State Co. for Textile Industries in Hilla, and brightly colored curtains are everywhere. They cover the taped-over windows. They hang from the ceiling. They sit on top of a stack of pillows. Just as Brinkley stands to present the check, the lights go out. "Every time the power goes out, it takes my machines one hour to reset," Fagah al Dhahab, the factory's director-general, tells the group, his voice rising with frustration. "I used to make a lot of money, but how can I compete with the rest of the world when my power goes out every couple of hours? When we can't work 24 hours a day anymore because my workers are afraid to work at night?" The lights come back on, dim, then go off again. Al Dhahab says production was up in July, but if he had extra money for generators and fuel, his workers would be even more productive during the single 7 a.m. to 2 p.m. shift. Brinkley smiles and says that if al Dhahab is a "good steward" of the $2 million, more funding could be made available. Just then the governor of Babil province, Salem al Mesalmawi, bursts through the factory doors with a gaggle of reporters and photographers in tow. He wants to talk about priorities. "The security situation is only getting worse," he says to the cameras. "That should be the priority here for these Americans." Inside the darkened factory, some of the looms look as if they've been idle for a long time. Workers with unbuttoned shirts and angry faces surround Brinkley and the governor, blocking the exit. At first there are polite questions. Then it becomes a shouting match. "How do I feed my wife and kids?" one man yells in Arabic. "How can I survive on only 93,000 dinars [about $75] a month?" another asks. Eventually the police clear the workers out of the way, and the governor's motorcade speeds off. Brinkley walks quickly to his armored personnel carrier. The questions remain unanswered. "I am dead tired," Brinkley says one evening, stuffing his bulletproof vest into a duffle bag before catching a flight back to Washington. His normal ebullience is gone, replaced by a reflective, almost despondent mood. "When I talk to my kids every night, they cry about when I'm coming home." We're in the villa in the Green Zone where his team lives. The house is '70s-style grand, with mirrored walls, but his quarters are cramped. There's a twin bed along one wall, bunk beds along another, and two recliners in the middle. The hallway smells of sewage. The windows are blacked out. "I certainly don't want to come across like I'm selling anything," Brinkley says. "Iraqis just need to feel like, Here's a group of Americans who think we're okay. They haven't heard that. Ever." Brinkley says he will reopen more factories in September - just in time for Gen. David Petraeus's report to Congress on the effect of the recent troop surge. Petraeus, the commander of U.S. forces in Iraq, says Brinkley's task force is key to his efforts to stabilize the country. "It's all well and good to have a goal of a vibrant free-market economy with expanding employment opportunities, private investment, and everything else," the general says, sitting in his windowless office in the Green Zone. "But we're quite a long way from that in this country, no matter how optimistic you are. And if you accept that, and if you want to see people working and producing, then you have to start up some of these state-owned industries." Bob Looney, an economics professor at the Naval Postgraduate School who has studied Iraq's reconstruction, doesn't share the general's view. "What he's doing," Looney says of Brinkley's plan, "is an act of desperation more than anything else. You've got to take care of the security problem first. It's sad to say, but he's just wasting his time and our money." Brinkley says he's tired of having to rebut such claims. Sitting in his bedroom, he pulls a stack of letters out of a bag. They're handwritten in Arabic. "People thrust these in my hands when we were at the pharmaceutical factory the other day," he says. "I got some of them translated: 'Please give me back my job.' 'Please help me.' What are we supposed to do? Ignore it?" Maybe not. Brinkley has helped steer $180 million a month in U.S. contracts to Iraqi businesses. He has put at least some Iraqis back to work. But even at the bus factory, Brinkley's favorite success story, there are few buyers other than the U.S. government. And the mood is far from upbeat. One morning not too long ago, a bus full of workers on their way to the factory blew up. Four died, 24 were wounded. Brinkley doesn't think there's a link between his work and the bombing. Perhaps. That only makes the job of putting Iraq back to work all the more daunting. |

Sponsors

|