Curse of the $500 million sunken treasureGreg Stemm's company found the richest trove of sunken treasure ever, writes Fortune's Tim Arango. Now comes the hard part: Keeping it.(Fortune Magazine) -- On April 10, a Gulfstream G-V took off from the British territory of Gibraltar en route to Tampa with a load of Colonial-era silver and gold coins salvaged from a centuries-old shipwreck. On May 16 a chartered Boeing 757 made the same journey, its cargo hold jammed with even more coins - this time over half a million of them, weighing about 17 tons.

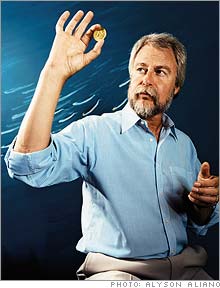

Today all those coins are locked up at a secret location in Florida. And if those who discovered the loot are to be believed, there's plenty more where that came from - some estimates put the total haul at $500 million, which would make it the richest find of sunken treasure in history. Where is this treasure, exactly? Odyssey Marine Exploration, the Tampa-based company that found it, won't say. The company won't even reveal the name of the sunken ship; the site is code-named Black Swan, after a book of the same name about unpredictable but consequential events. All we really know about Black Swan is that it's in international waters 100 miles west of Gibraltar under 3,600 feet of ocean - and that the Spanish believe it all belongs to them. It's a wonderful drama, straight out of a Clive Cussler thriller: precious metals, races against time, undersea robots, and international intrigue. How that intrigue turns out could be a watershed for Odyssey and its shareholders. Wait. Shareholders? That's right, Odyssey (Charts) is a public company. The idea of searching for sunken treasure might strike some as a boyish fantasy - fine for Cussler et. al., but not for a sophisticated modern corporation. And Greg Stemm, co-founder and co-chairman of Odyssey, probably wouldn't disagree with that. "Let's see. You have no experience, and you're going to buy a research vessel to look for shipwrecks. Oh, sure, I'll invest in that," says Stemm, a trim, gray-bearded man of 50 whose only remotely relevant work experience before getting into the business in 1986 was running a dinner cruise in Jamaica. (He also worked in advertising and was once Bob Hope's press man.) But Odyssey has proved seductive to investors - even after a Securities and Exchange Commission investigation forced Stemm and his partner, Odyssey's co-founder, John Morris, from their first company, Seahawk Deep Ocean Technology, in 1994 for allegedly overstating the value of artifacts it recovered from a wreck off the Florida Keys. Stemm and Morris fought the SEC in court and won - which paved the way for the pair's return to the ocean's depths. There's plenty to find down there. Unesco has estimated there are about three million shipwrecks worldwide, but in only a fraction of cases - fewer than 1,000, by Stemm's reckoning - does it make economic sense to send a $4 million underwater robot to look for treasure. "There's billions of dollars scattered on the ocean floor - that's a fact - and we have the technology to find it," says Stemm, working through a seafood lunch in a Tampa mall five minutes from Odyssey's offices. "The business model is very simple. The execution is complex." The company holds a pitch meeting every Thursday in which its researchers, each of whom covers a part of the world, toss out ideas culled from studying old maps and ship logs. It's a slow process: Odyssey has been in business since 1997 but, pre-Black Swan, had found just one big revenue-generating trove. That was the 2003 discovery of the S.S. Republic, a Civil War-era steamship that sank in a hurricane off the coast of Georgia in 1865. According to an SEC filing, as of the end of last year Odyssey had sold $33 million worth of coins from the Republic, and it has plenty more in its inventory. "It might take us 20 years to sell all the coins from the Republic," Stemm says. Odyssey, which doesn't issue financial guidance nor hold quarterly earnings calls, is still waiting for sustained profits: In 2004, when the coins from the Republic first hit the market, the company earned $5.2 million in net income on revenue of $17.6 million. By last year revenue had slipped to $5.1 million, and the company lost $19.1 million. Then, in mid-May, on the day after Black Swan was announced, Odyssey's stock jumped 81%. (The price fell in subsequent days, but as Fortune went to press, OMEX remains about 32% above where it was trading before the discovery announcement.) The goal is to find enough shipwrecks to sustain the business in other ways. Odyssey sells tickets to an exhibit at Tampa's Museum of Science and Industry, which features a replica of Zeus, a submersible robot that uses a claw and suction device to pick up artifacts from the ocean floor; every one of the Republic's thousands of coins was retrieved that way. And the company is close to announcing a TV show Stemm describes as "Jacques Cousteau meets Deadliest Catch," the latter being the Discovery Channel show about crab fishermen in Alaska. "Another shipwreck or so and we'll have enough inventory for the foreseeable future," says Stemm. For that to happen, Odyssey will need lots of luck - and, as the kingdom of Spain has made clear, really good lawyers. When news of the Black Swan discovery hit newspapers in mid-May, Spanish officials sprang into action. On May 31, Madrid made a claim in U.S. District Court in Tampa - a legal maneuver aimed at forcing Odyssey to reveal details about the ship. Jim Goold, a Washington, D.C., attorney and underwater archaeologist who represents Spain, told Fortune, "There's very strong reason to believe that what Odyssey has done is strip a sunken Spanish ship of valuables. That's why we're seeing an extraordinary effort to maintain secrecy." That's one interpretation of Odyssey's silence. Another is that it's simply afraid of a gold rush. "This is an industry that no one cares about until someone finds something," says professor David Bederman, a maritime-law expert at Emory University School of Law and an Odyssey board member. "If you're lucky enough to find something, everyone will make a claim, whether it's legitimate or not." Back in Spain a judge ordered a criminal investigation, and when Odyssey's vessel Ocean Alert, a 240-foot boat loaded with millions of dollars of sonar equipment, was leaving the Port of Gibraltar in July, armed members of the Guardia Civil boarded the ship and forced it to dock in the Spanish port of Algeciras. "Odyssey's crew and attorneys were forced by the Spanish officials to sit in the scalding sun for approximately seven hours without food or water or use of the restroom," according to a court filing. Authorities seized the hard drive belonging to a company attorney and the notebooks of a reporter for the Gibraltar Chronicle, who was along writing a story. The company's other ship, Odyssey Explorer, a 251-footer that deploys the Zeus, remains effectively blockaded in Gibraltar. (The company often charters boats to foil amateur treasure hunters, who tend to track Odyssey's two-vessel fleet rather obsessively.) The controversy created a media storm in Spain. "It's probably as big a story as our subprime meltdown is here," Stemm says. In the States the story took on a political tinge. Noting that presidential candidate John Edwards is an investor in Fortress (Charts), the big hedge fund that is one of Odyssey's largest shareholders, a New York tabloid blared: "Avast, matey! Is John Edwards a pirate? The Spaniards say yes, and they want their plundered loot back." Odyssey stores most of its shipwreck take in its conservation center, a squat building near the company's headquarters. The walls are covered with undersea photos, including a tantalizing shot of coins scattered at the Republic site called "Carpet of Gold." On shelves are bric-a-brac from other explorations: old medicine bottles, shot glasses, religious artifacts, and porcelain. In the fridge are still-corked bottles of beer, peaches, and gooseberries from the Civil War era. "It's all about sharing the excitement with the public," Stemm says. What you won't see in the conservation center, for now, are the real valuables, the coins that fuel Odyssey's business. Those are kept at that secret location - the same place that holds the Black Swan haul as it awaits various court decisions. If the company prevails, it'll have that massive hoard to draw on for years to come. But even if it loses, Black Swan won't be Odyssey's last big project. Up next is a deal with Britain to salvage the H.M.S. Sussex, a Royal Navy ship that sank in the Mediterranean in 1694 carrying gold for the Duke of Savoy. Estimated value: a cool $1 billion. |

|