What price glory?

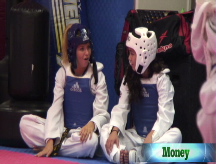

Two athletes - one American, one Chinese - are striving for Olympic immortality in the same sport. But the cost has been high, in both money and family sacrifice.

|

| Charlotte Craig, U.S.Olympic Taekwondo team |

|

| Luo Wei, Chinese Olympic Taekwondo team |

| MMA | 0.69% |

| $10K MMA | 0.42% |

| 6 month CD | 0.94% |

| 1 yr CD | 1.49% |

| 5 yr CD | 1.93% |

(Money Magazine) -- Although they live on opposite sides of the world, Charlotte Craig and Luo Wei share the consumer habits typical of their generation. Craig, a shy 17-year-old from Murrieta, Calif., texts her friends on her cell. She goes to the mall. She paints her fingernails black and her toes pink.

Six thousand miles away in Beijing, Luo, 25, wears Nike sneakers. She loves fragrances such as Burberry London. And she splurges on cell phones, like her new $285 Samsung.

Oh yeah, one other thing these young women have in common: In a half second, both of them can knock you flat with a spinning hook kick to the side of your head.

Craig and Luo are world-class practitioners of the martial art of taekwondo. And both are headed to Beijing in August to represent their country in the Olympic Games. Craig, a bronze medalist at the 2007 World Championships, will be one of four U.S. team members (the other three are siblings Steven, Mark and Diana Lopez). And while Craig isn't favored to win gold - reigning world champ Wu Jingyu of China has that honor in her weight class - she has a good shot at bronze or silver.

Luo, who took home gold at the 2004 Athens Games, had hoped to repeat her medal-winning performance until she was sidelined by injury. Now she's an alternate for the Chinese team and would need a minor miracle to put her back in contention.

The young women have never competed head to head - Craig, at five feet, five inches tall and 108 pounds, is a fin/flyweight; Luo, five feet, 11 inches and 148 pounds, is in the middle/heavyweight division. But on the mat or off, both routinely display the traits that define Olympians. Innate physical gifts, of course. A hunger to succeed. A willingness to put in several hours a day, year after year, of intense training.

But elite athletes like Craig and Luo need something else: money, and lots of it. The bills for coaching, training facilities, tournaments and other expenses easily add up to tens of thousands a year. For young American athletes, that financial burden falls squarely on their parents; for Chinese youth, the government picks up the tab - if they're good enough.

Either way, the Craig and Luo families have learned it takes gold to make gold. And both have sacrificed much along the way to make their daughters' Olympic dreams possible. To get to a similar place, though, they've taken very different journeys.

In an odd way, their stories mirror those of their countries and their economies - one is an example of a family's rugged individualistic effort; the other an illustration of the difficulties and opportunities in transitioning from a society totally supported by the government to one in which old-fashioned free-market ingenuity is the swiftest route to success.

When Luo Wei was in third grade, she competed in her Beijing school district's track meet - and placed first in each event. "I was really surprised when she won," says her mother Luo Zeyu, 49, through a translator.

But her daughter's achievement was more than cause for parental pride; it presented a financial opportunity as well. In China, where the government is focused on solidifying the country's international standing as a sports powerhouse, children who show promise as athletes enjoy benefits ordinary kids do not: a chance to land a salaried position on a government-funded sports team and a big advantage in the intensely competitive university admission process.

So Zeyu enrolled Wei, then eight, in a sports boarding school, where four hours of rigorous daily training was piled on top of a full academic schedule. It wasn't cheap. While China aims to provide free education, funding shortages can result in private-school-caliber fees for favored institutions.

Zeyu initially paid more than $400 a year for Wei's school; by middle school the cost was up to $1,500, at a time when 97% of urban Chinese households made $3,500 or less. Nothing ventured, nothing gained, explains Zeyu, quoting a Chinese proverb. Literal translation: "You have to risk the baby to catch the wolf."

That Zeyu could afford her daughter's tuition was a testament to her own talents, and the opportunities afforded by a changing China, where a series of economic reforms over three decades has transformed the Communist nation into a hotbed of capitalism.

After graduating from high school in 1976, Zeyu got a job assembling audiocassette recorders in a factory, earning less than $1 a day; by the late 1990s she had worked her way up to a sales and marketing position at a state-owned manufacturing firm that paid as much as $30,000 a year, putting her in the top 1% of urban Chinese households.

Her marital life wasn't as blissful; her marriage to Wei's father broke up after their daughter was born in 1983. She married again and had a boy, Sun Hao, in 1991 but was widowed a few years later.

Despite Zeyu's hopes for her daughter, however, Wei never became good enough to be competitive at a national level in hurdles, the track event in which she specialized. Homesick, the youngster considered giving up several times, only to be urged by Zeyu to keep trying. "My mother has always been there for me, encouraging me when I want to quit," Wei says.

Then one day, near the end of middle school, Wei and Zeyu were approached by a taekwondo coach looking for promising students, part of an effort by Chinese athletic officials to develop teams in newer Olympic sports with less entrenched competition. Neither Luo was familiar with taekwondo, which only became a full-fledged Olympic sport in 2000. "Is that what you see in those kung fu movies?" Zeyu asked the coach.

Luo Wei's long legs, which had helped her in hurdling, also made her well suited to the Korean martial art, which puts a big emphasis on kicking. Most points are scored with the feet - one point for a solid kick to the body, two for a kick to the head.

So at 15, Wei took up taekwondo. She gained tuition-free enrollment at the Beijing Shichahai Sports School, one of China's most prestigious, and began collecting a stipend from the provincial government that started at about $70 a month. She soon grew to love and excel at her new sport.

"Taekwondo requires not only your physical strength but also your mental strategies," Wei says. A mere five years after switching sports, she won gold at the 2004 Olympics in Athens.

Wei has since enjoyed handsome economic rewards that come to top athletes in China. First, there was the $28,500 in tax-free prize money that she got from the government for winning the gold medal (though China has had personal income taxes since the 1980s, governmental awards for sports achievement are exempt).

In addition, she earns around $17,000 a year as a member of the Beijing and national teams (95% of urban households make less than $7,700) and gets additional income from company sponsorships and government performance bonuses. Total earnings: up to $160,000 in her best year (2004). Meanwhile, the state picks up the bill for her expenses, including lodging, travel, training, even the acupuncture that's part of her physical therapy routine.

Combining Wei's sports earnings with Zeyu's salary has enabled the two women to become real estate mini-moguls (yes, you can own real estate in China). In 2003, Zeyu moved out of the one-bedroom apartment she got rent-free through her old job and bought, with her daughter, a three-bedroom apartment in Beijing for $170,000, putting 50% down.

Since then they've paid off the mortgage and the place has more than doubled in value, to around $400,000. Last year the two pooled $60,000 in cash to buy another apartment in a building reserved mostly for elite athletes. Zeyu moved out of the old apartment, which she now rents out for nearly $900 a month, and into the new one.

Zeyu lives large by Chinese standards. She drives a 2003 Buick Regal, purchased five years ago for $60,000. And while the apartment complex looks desolate from the outside, inside her place is comfortable and bright, with a big pink couch in the living room and a 50-inch flat-screen Samsung TV that cost $6,000.

Zeyu hasn't needed help from her daughter to acquire such luxuries. She's done quite well in her own right. In 1998 she shifted into civil engineering, bidding on projects such as a major port facility in the city of Dalian. Depending on the jobs her construction firm won, she has made as much as $70,000 a year. But now, she says, she's ready to retire this fall.

She won't get much help from the Chinese government. Her $150-a-month pension won't be enough to maintain her standard of living, and the country's strained Medicare equivalent won't cover most of her medical care. "We are in a transition period," says Liu Feng of the Financial Planning Standards Council of China. "Suddenly people are going from not having to take care of anything to having to take care of everything."

Luckily, Zeyu has probably saved quite a bit, though she won't disclose how much (in 2005 the average savings rate in China was 37% of household income, according to the McKinsey Global Institute, vs. 1% in the U.S.).

About 40% of her money is in a low-interest savings account; she sank most of the rest in a privately held logistics firm, which she hopes will provide her with dividend income in her old age. The balance, about 10% of the total, is in mutual funds. She's unwilling to invest more in funds because she doesn't trust the market. With good reason: China's Shanghai exchange endures stomach-churning swings - it lost half of its value from October 2007 to April of this year.

Wei, meanwhile, has suffered a setback of her own. In April 2007, four months after winning gold at the Asian Games, she suffered deep vein thrombosis, hampering her performance at the World Championships a month later. Her defeat in the semifinals put her out of contention for the Olympics.

Now an alternate for the team, she still trains intensively, starting with aerobics at 6:15 a.m. and ending with an evening session of physical therapy. "It's disappointing that when the Games are hosted in my city, I probably don't have a chance to play," she says.

If she wants to someday, Wei can probably become a coach for the team; in addition to her athletic experience, she earned her college degree in 2006 from Beijing Sport University. But she'd rather not talk about that.

She's not too keen on discussing her finances either. When pressed, she will share tidbits about investment strategies (2008, the Year of the Rat, is good for fast-paced trading, she says). Not that she has much cash to invest - like many people her age. Unlike her mother, she says, "I never save money. What's important is to make money, not to save any."

Which makes it all the more pressing for Wei to consider what she'll do and how she'll support herself once she's no longer competing. But it's tough when she's preoccupied with training exercises, axe kicks and a too-elusive dream of more gold - if not in 2008 then in 2012. "All I think about is performing well," she says.

Send feedback to Money Magazine