When a staffer switches genders

Coping with major changes can flummox a workplace, but you can protect your bottom line and your employees by promoting tolerance and respect.

|

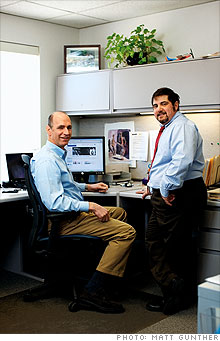

| Madison Co. supervisor Tony Ferraiolo (standing), with owner and president Steve Schickler. |

|

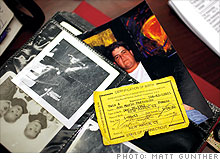

| Tony Ferraiolo's birth certificate and photos from his earlier life as a woman. |

(Fortune Small Business) -- Tony Ferraiolo will never forget his first day back at work after surgery. The 46-year-old supervisor's knees trembled as he entered the windowless headquarters of Madison Co., a switch and sensor manufacturer in Branford, Conn.

Under the curious gaze of his colleagues, Ferraiolo crossed the plant floor and settled into his office. A few minutes later, Madison owner and president Steve Schickler walked in and sat down. "So you're a 'he' now, right?" Schickler asked. Ferraiolo nodded. "Good enough," Schickler said briskly. "I'll let the managers know."

For Schickler, 50, there was no question about what would happen next. Ferraiolo would continue to supervise more than half of the plant's 50 employees. Life would go on as before, with one small difference: Ferraiolo would no longer use the ladies' room.

Schickler describes his decision to support the transgender employee formerly known as Ann Ferraiolo through the transition as a no-brainer.

"If you start limiting your choices in staff based on this kind of thing, you're cutting yourself off from a lot of good people," he says. "We could have lost a valuable manufacturing supervisor - it was as simple as that."

Most employers will never have to deal with a transgender worker: Estimates of the transsexual population in the U.S. are vague but relatively low, ranging from less than 50,000 to 600,000 (not including those who choose not to undergo sex reassignment surgery). Nonetheless, gender identity has become the latest battleground in workplace discrimination law, which no business owner can afford to ignore. And given that few small businesses boast dedicated HR teams, it's particularly important for management to set a tone of workplace tolerance and respect.

The concept of workplace discrimination as a federally prohibited practice emerged in the early 1960s with Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the creation of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission to enforce that statute. Initially Title VII prohibited discrimination by employers based only on race, color, religion, sex or national origin, but over the decades its interpretation has evolved in the courts and its mandate has been supplemented by Congress. For example, Barnes vs. Costle (1977) - in which an appellate court found that Title VII applied to a woman's claim that she had been sacked because she rejected her boss's sexual advances - helped broaden the definition of sex discrimination to include sexual harassment. Further legislation has added age, pregnancy and disability to the list of prohibited discrimination.

As a result, many kinds of employment prejudice can end up costing businesses dearly in court. And in a shrinking post-baby boom labor market, excluding skilled workers for any reason unrelated to the job is likely to put a business at a competitive disadvantage. That fact hasn't been lost on the Fortune 500.

In the past five years, 322 major companies, including Shell Oil and Unilever, have added gender identity to the classifications covered by their nondiscrimination or equal opportunity policies, according to the Human Rights Campaign Foundation, a Washington, D.C. nonprofit that advocates for the rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender Americans. The law is close behind: Twelve states prohibit workplace discrimination based on gender identity, and federal courts are increasingly favoring transgender plaintiffs who bring discrimination suits against employers.

"As society progresses, more employees are emboldened to seek rights and protections," says Michelle Phillips, an attorney who specializes in workplace discrimination cases.

Smaller companies face particular challenges in this regard. "Small businesses may not have the infrastructure in place to ensure that best practices are being utilized and to deal with complaints and investigations," Phillips adds.

Madison's human resources infrastructure consists of only one person, business manager Donna Dotson. Nonetheless, the company has been largely successful in accommodating its first transgender employee. Ferraiolo approached Schickler and Dotson about his decision to switch genders in late 2004. The realization had come, he says, months earlier when he saw a documentary about transgender people. He was astounded.

"I never knew a female could become a male," says Ferraiolo, who had identified as a lesbian for years but always felt painfully uncomfortable in his female body. "When I saw that video, I realized that was what I wanted and who I was." Within a week Ferraiolo had asked friends outside of work to address him as "he." But at work he was still regarded as a woman even though he had already changed his legal name to Tony.

Then Ferraiolo decided to undergo chest-reconstruction surgery, an elective procedure that he paid for out of his own pocket. He would need three weeks off from work. With some trepidation he told Dotson and Schickler, but neither was as shocked as he'd expected. "Tony was Tony," Dotson explains. "He was never all that feminine, so it didn't faze us too much."

From the get-go, Schickler and Dotson made it clear that they expected the entire staff to treat Ferraiolo with respect. Schickler met with Madison's five senior managers, who made sure that everyone got the message. "I think that anyone who might have had a problem with Tony's decision looked around and saw that the culture was going to be supportive," Schickler says. "That set the tone."

When Ferraiolo returned to work in March 2005, he had a man's chest and boasted an impressive goatee, grown without resorting to hormones. But becoming a man posed a thorny question that hadn't been discussed before surgery: Which restroom should he use?

For the first two weeks, Ferraiolo trekked to the bathroom at the gas station down the street. "I'm not the type to walk straight into the men's room," he says. "I'd supervised these guys for six years, and I didn't want to be rude." Eventually Ferraiolo and Dotson agreed that he would use the single-cubicle men's toilet in the front office.

It may seem trivial, but the restroom question can easily flummox managers who must balance a transgender employee's needs against those of the rest of the staff. Many specialists advise against asking a transgender person to use a segregated bathroom beyond an initial adjustment period, simply because it won't help reintegrate the employee. "If a person is presenting as a woman, we recommend she be treated as a woman, which includes using the women's restroom," says Janis Walworth, a consultant on transgender issues.

What if the employee hasn't had gender reassignment surgery and lacks the "right parts"? Walworth advises against anatomical requirements for restroom access, given that most gender reassignment candidates are required to live in their desired gender for a year before an operation. Moreover, many transgender people do not undergo surgery. "What's between your legs is irrelevant to doing the job," Walworth says. "Surgery is private medical information and shouldn't be anybody else's business."

The biggest adjustment for everyone at Madison was undoubtedly the change of pronoun that accompanied Ferraiolo's transition. "That was one of the most difficult things to do," Dotson says. " 'She' would flow out of your mouth before you could think about it." One colleague told Ferraiolo that it was against her religion to accept his new identity. She came around after some discussion, Ferraiolo says. But she calls him only Tony, avoiding pronouns altogether. Others still address him in the feminine.

"I think some people are just limited," says Ferraiolo. "Even if they knew how much it hurt my soul when they use the wrong pronoun, I'm not sure they would stop."

Ferraiolo has become a better manager since he changed genders. Before the transition, Schickler would often coach Ferraiolo on improving his people skills. "Tony was very aggressive before," he says.

Ferraiolo agrees. He remembers feeling angry all the time, and he would often shout at the workers he supervised. "I wouldn't have wanted to work for me," he admits. "Now I'm more relaxed, so I have better relationships with the employees."

Specialists in transgender issues recommend holding a staff meeting before the employee's transition, to answer questions from the staff and to make sure everyone understands what constitutes harassment. But what about clients? Ferraiolo supervises workers on the plant floor and rarely deals with outsiders.

Not so for Sarah Sands, 49, a transgender technical-services supervisor at Golden Artist Colors, a paint manufacturer in New Berlin, N.Y. Formerly known as Isaac, Sands transitioned from male to female in 2003. On her last day as Isaac, she sent a simple e-mail to customers announcing that she would return to work as Sarah. If anyone called asking for Isaac, Sands would take the call, inform the caller that she was now Sarah and ask how she could help. She found the response surprising. "The feedback I got was very positive, you-go-girl type of support," she says.

The lesson? Tolerance can be good business as well as good karma. "An employee with a visibly different lifestyle choice from the employer sends a message that this is an accepting business environment," says Phillips, the workplace discrimination attorney. "That often leads to more customer loyalty and better business."

Sands and Ferraiolo both had supportive bosses who were willing to help them through the transition. Had they been let go, however, they could have taken their employers to court. One recent precedent: Diane Schroer, a male-to-female transgender person and 25-year military veteran who successfully sued the Library of Congress for discrimination.

In 2004 Schroer applied at the library for a job as a terrorism specialist. Not having yet started her transition, she identified herself as David, her legal name at the time. When officials offered her a job, she told them she intended to become a woman before starting work. The offer was rescinded a day later.

With the ACLU, Schroer sued under Title VII. (Because no federal statute explicitly covers discrimination based on gender identity, plaintiffs often claim sex discrimination under Title VII.) Last September, the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia ruled in her favor, noting that the library had refused to hire Schroer "because her appearance and background did not comport with the decisionmaker's sex stereotypes about how men and women should act and appear."

Observers hailed the court's decision as a landmark. Schroer vs. Billington marked the first time a judge had explicitly ruled that gender discrimination was a Title VII-prohibited form of sex discrimination.

Back in Connecticut, Tony Ferraiolo's driver's license still bears an F for female, even though he sports a goatee in the photograph. To legally change his gender in Connecticut, he would need to submit a medical diagnosis of gender-identity dysphoria. Ferraiolo won't do that. "Some say dysphoria, some say disorder," he argues. "I say, nah, I was just born into the wrong body."

Whether or not employers agree with this assessment, they must tread a fine line between fostering mutual respect among workers and appearing to endorse what some perceive as controversial lifestyle choices. "This shouldn't be about trying to convince workers that being transgender is a wonderful thing," says Ramapo College law professor Jillian Weiss, author of Transgender Workplace Diversity. "It's about the employer arranging an environment that's positive and respectful toward everyone." ![]()

Unusual perks: Goldman Sachs covers sex changes

Discrimination landmarks: Legal precedents

Obama's first law: The fight for fair pay

Overtime pay: A ticking time bomb

-

The Cheesecake Factory created smaller portions to survive the downturn. Play

-

A breeder of award-winning marijuana seeds is following the money and heading to the U.S. More

-

Most small businesses die within five years, but Amish businesses have a survival rate north of 90%. More

-

The 10 most popular franchise brands over the past decade -- and their failure rates. More

-

These firms are the last left in America making iconic products now in their twilight. More