Renewables: America's next heavy industry

How three manufacturers in three Midwest states are picking up where the auto sector is laying off.

|

| Molten iron is prepared for casting at Ohio's Minster Machine Company. The company recently expanded into making parts for the wind industry. |

|

| Minster Machine Chief Executive John Winch beside one of his firm's windmill hubs, the piece that attaches the blades to the tower. |

|

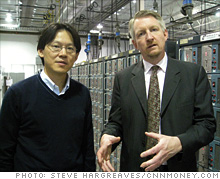

| EnerDel head Ulrik Grape and Chief Operating Officer Naoki Ota next to a testing bank for electric car batteries outside Indianapolis. |

|

| Saginaw, Mich. resident David Denno hopes to get a job at Hemlock Semiconductor, a local factory that's branched into making silicon for solar panels. |

MINSTER, OHIO (CNNMoney.com) -- About 200 miles south of Detroit, America's industrial heartland gives way to the Ohio countryside.

Here lies the tiny town of Minster, off I-75 past the Ford factory, the Mazda factory, the Jeep factory and the massive coal and nuclear plants that keep them all running.

Surrounded by farms, a family-run manufacturer is getting in on the business everyone from President Obama on down hopes will clear the air, wean the country off imported energy, and replace the fast-disappearing auto jobs: Making parts for the burgeoning renewable energy sector.

For the last two years, the Minster Machine Company has been forging the giant cast-iron hubs that keep the blades attached to the center of a wind turbine.

"The wind market for us was a diversification strategy," said John Winch, who followed his father, grandfather and great-grandfather in helming the 103-year old company. Minster Machine also makes the equipment that make the parts for the auto, medical and food industries, among others.

But it's more than just a diversification strategy. It's a bet that the market for renewable energy products will take off.

Because Minster Machine has skilled metal workers, its own foundry and a huge factory floor, making the hubs for wind turbines and other large wind components is an ideal area for the company to get into.

Minster Machine hopes to use all this, and proximity to wind farms on the Great Plains to expand, and that could mean more jobs. Wages at the company start at $17.50 an hour and go up from there.

"The renewable energy market could be akin to an industrial revolution-type event," said Winch. "We want to be in that space."

So do a lot of other firms.

Scores of firms in the renewable energy business have recently opened in the Rust Belt states. They hope to take advantage of a population known for its industrial skills, engineering ability and work ethic.

It's hard to say how many people these firms currently employ. The government doesn't yet track green jobs and the distinction between what's "green" and what isn't often gets blurred.

One study by the University of California, Berkeley estimated that green energy companies employ at least half a million people. That number could climb to 2 to 4 million over the next 15 years if the nation got 15%-20% of its power from renewable sources.

If those job numbers materialize on the high end of estimates, the nation's total manufacturing workforce would get boosted by about 25%.

In the Midwest, it's clear that local officials have high hopes for the industry.

"We very optimistic and very confident that this is a whole new industry and can be a key part of our economic development strategy," said Ohio's Lt. Gov. Lee Fisher.

There's certainly a lot of room to grow.

With fewer subsidies compared to Europe, the United States failed to attract many renewable energy manufacturers over the last few decades. Many experts say the country lags behind in this emerging space.

While the wide swath of land from Texas to North Dakota is one of the best places in the world to produce electricity from wind, more than 50% of the parts used in U.S. wind turbines are imported, according to Ed Weston, director of the Cleveland-based Great Lakes Wind Network.

With each turbine containing over 8,000 parts, that could represent a lot of jobs.

"This is craft work. These are the manufacturing trades coming back to life," said Weston. "This is not unskilled labor at all."

It may not be unskilled labor, but some studies suggest these new green jobs don't pay nearly as much as some of the jobs they are replacing, like union auto jobs.

Many green jobs pay only $11 or $12 an hour, according to Philip Mattera, research director at Good Jobs First, a labor-friendly research group. That compares to an average of about $19 an hour for production workers in heavy industries as a whole, he said. Meanwhile, an autoworker can make $30 an hour or more.

"Green jobs are not automatically good jobs," said Mattera.

One state government official said green manufacturers are reluctant to set up shop in union towns, fearing an inflexible workforce expecting higher wages.

Some are skeptical the new sector can take off as quickly as everyone seems to be hoping. "We haven't drank the Kool-Aid," said the official who did not want to be named.

Still, even the traditional manufacturing industry is welcoming the new business the green energy industry could bring.

"We are at the very beginning of this process," said Alan Tonelson, a research fellow at the U.S. Business and Industry Council, which represents smaller and mid-size manufacturers. "But this could spark the third or fourth global industrial revolution."

Just north of Indianapolis one company is trying to do just that.

In an office park nestled among the software and biotech firms ringing this diverse manufacturing city that has largely escaped Rust Belt status, EnerDel is aiming to perfect the battery that will let electricity replace gasoline as the main fuel in cars.

EnerDel, a division of Ener1 (HEV), is one of just a few American companies that has the technology to compete with the big Asian battery makers. Advances in this field happen quickly, and the company that comes up with a cost-effective design will likely reap huge profits.

The feeling of a company racing to compete is unmistakable here. Scientists feverishly work on the new technology and scurry to hide it from our camera as we toured their spotless facility.

"A trained engineer could tell what's in there just by seeing the size of it from the outside," said one worker, sliding what looked like, to this untrained eye, a box inside another box.

The company has applied for a $480 million loan with the government's advanced vehicle program. If the loan comes through, EnerDel plans a huge expansion, and would add some 2,800 employees to its current workforce of 150. A 3,000-person plant is about the size of a large auto factory.

"We're talking about a serious growth in people," said EnerDel Chief Executive Ulrik Grape.

Production jobs at the company start at $12 to $15 an hour. The pay for the many scientific jobs required in the battery field is far higher.

In Ohio and Indiana people love the idea of renewables. In a hip bar in downtown Indianapolis, a young woman and her mother couldn't agree on much: Whether the city has a good art and music scene, is a good place to raise a family, etc. But they did agree that people will embrace renewable energy companies both for the jobs and out of a desire to help the planet.

In Ohio the mood was similar, although people in both states stressed the situation for workers wasn't as dire as it is up north in Michigan.

"We've got a very strong manufacturing base," Jeff Buschor, a 48-year old mortgage broker, said over breakfast with other local businessmen at a diner near Minster. "Sure, the auto guys are down, but the others can keep the community up."

In Saginaw, Mich., the mood is quite different.

"This town has always had a multitude of supplier shops to the auto industry, and they're peeling off like onion rings," said Pat Johnson, a retired heating and air conditioning dealer. "It's kinda gloomy."

Fortunately for Saginaw, just a few miles west of town lies Hemlock Semiconductor, a sprawling silicon maker owned by Dow-Corning, a joint venture between industrial heavyweights Dow Chemical (DOW, Fortune 500) and glassmaker Corning (GLW, Fortune 500).

Hemlock makes the silicon wafers for electronic chips and, since 2001, solar panels. And they're expanding big time.

Polysilicon for solar panels now accounts for over 60% of the firm's sales, and Hemlock is the major supplier for seven of the world's top 11 solar panel makers.

The company recently announced a $1 billion expansion at its Michigan facility and plans for 300 to 400 new hires.

That's good news for people like David Denno, a former auto worker in Saginaw who's now looking for a job.

"That's one of the places I'm trying to get into," said Denno.

Firms like Hemlock may not pick up all the slack from auto sector layoffs, and they may not pay the higher union wages, but for Denno and others like him, they're hope that decent manufacturing jobs are still out there. ![]()