How health reform may help ... or hurt

Fixing health care has giant consequences. Here are the potential economic rewards for getting it right and the perils of getting it wrong.

NEW YORK (CNNMoney.com) -- Americans are being told daily that health reform isn't just the right thing to do -- it will also help save the economy.

"Health care reform is not part of the problem when it comes to our fiscal future, it is a fundamental part of the solution," President Obama said in a recent address.

The crux of the problem: The United States spends far more on health care than do other developed countries, but it often gets far less bang for its buck. Meanwhile, a large number of Americans either can't afford insurance or have insurance that doesn't adequately cover their medical costs.

The kicker, of course, is that rising costs are making the country's long-term fiscal picture very, very ugly.

For many, the Washington debate over the mind-bending details of different options obscures the issue of what's at stake. What is the threat to the economy if no action is taken? What happens if a health system overhaul succeeds ... and what are the economic perils if it fails?

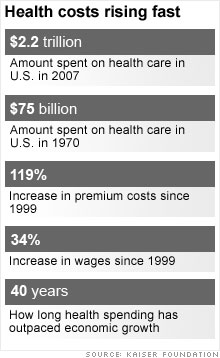

For 40 years, health care costs have grown faster than inflation and wages.

Today, the United States -- including the government, employers and individuals -- spends more than 16% of its gross domestic product on health care, or $7,421 per person, according to the Kaiser Foundation.

If health care costs grow unabated, the country is on track to spend more than 20% of its GDP on health by 2018.

In other words, 20% of the value of goods and services Americans produce will be spent on health care alone.

The more we spend on health, the less we'll have to spend on other things. That can hamper economic growth and means there will be less and less money available to support education, defense and other priorities.

Meanwhile, the country's already record high debt is set to swell to unsustainable heights due largely to rising health care costs, which expand federal spending on Medicare and Medicaid.

By 2035, the Government Accountability Office estimates that all federal revenue -- taxes and fees paid by individuals and businesses -- will be consumed by Medicare, Medicaid and interest on the public debt.

"Virtually all of our long-term fiscal challenge is attributable to the rapid growth in health care costs. And unless we get them under control, our budget is doomed," said Robert Reischauer, former director of the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) who is now president of the Urban Institute.

Lawmakers note that higher health care costs put U.S. businesses at a competitive disadvantage because they have to pay so much more to insure their employees than do their foreign competitors.

Indeed, among developed countries, the United States is the biggest spender. It spends 52% more on heath per person than the country ranked second, which is Switzerland. Despite that, the United States does not necessarily do better in terms of health care access, quality or outcomes.

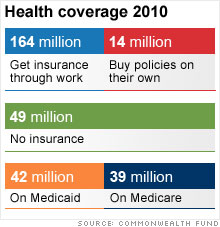

Meanwhile, the Commonwealth Fund estimates that currently 46 million people have no insurance, while another 25 million working-age adults are underinsured.

In a letter to lawmakers, the CBO made plain the consequences of letting health costs grow unrestrained.

"The country faces difficult and fundamental tradeoffs between limiting the growth of Medicare and Medicaid ... accepting a continuing increase in taxes ... and reducing other spending ... possibly to levels not experienced in this country in more than 40 years."

Arguably, there are three measures by which to judge whether health reform is successful from an economic standpoint. It would have to pay for itself over time; reduce health spending without compromising quality; and provide affordable, accessible care for everyone.

The CBO told lawmakers that a 1% reduction in the growth of federal health care spending each year for the next 20 years would pay for the cost of expanding coverage in the first decade and then provide savings that "exceed that cost in the next decade."

The desired end result of reform is less money spent for the same or better care and with better outcomes.

"If we do it right, it allows us to have a more efficient health care system ... and we can use the additional savings to invest in something, educate someone or pursue some other national goal," said Douglas Holtz-Eakin, a former CBO director.

Obama economic adviser Christina Romer estimates that if the annual growth rate in health care costs slows by 1.5 percentage points a year -- which she concedes is a high bar -- real GDP could increase by more than 2% in 2020 and by nearly 8% in 2030.

But GDP isn't the only measure of well-being.

"If people get better access to health care those people are better off," said Robert Book, a senior research fellow in health economics at the Heritage Foundation.

But the physical dividends pay off economically as well. That's because it's easier to generate income when you're healthy. And it's easier to stimulate the economy with your income when you're not bankrupted by a medical crisis.

One reason health reform hasn't happened yet: It is painfully hard to figure out how to do it right.

And economically, there are serious risks if health reform is done wrong.

For Book, reform will have failed if everyone gets covered but has to wait for essential care. "People will be sick, less productive and not get what they paid for," he said.

He believes taxing a portion of workers' health care benefits could lead to a more efficient use of health services. But, he said, using other tax increases to fund reform could place a drag on GDP.

If that happens, that will "mak[e] it far more difficult to escape the debt trap," wrote Harvard economist Kenneth Rogoff in a Financial Times op-ed.

To Holtz-Eakin, who advised John McCain in last year's presidential race, failed health reform would mean that "everyone gets coverage but we don't change the underlying cost dynamics. Health care spending goes up and we haven't solved our deficit problem."

In that scenario, health reform would make the deficit worse -- which "could prove the straw that breaks the camel's back," Rogoff wrote.

And the deficit could get worse even if lawmakers pass measures that can pay for health reform in full.

Here's why: some of the biggest savings from reform might not be realized for at least a decade because they will require key changes in how medicine works. In the interim, however, there is a risk that lawmakers will undermine those savings by tweaking reform policies -- such as succumbing to political pressure to defer scheduled payment cuts for providers.

If lawmakers are really serious about putting the federal budget on a sustainable path, the CBO said, that just won't do. ![]()