Nuclear waste: Coming to a town near you?

The nuclear industry could be on the verge of a major expansion just as the government cancels a plan to store the waste. Where's it going to go?

|

| Nuclear waste being stored in a pool at a power plant in southern Texas. The waste is safe here for decades, but critics say a more permanent solution should be found before many more plants are built. |

|

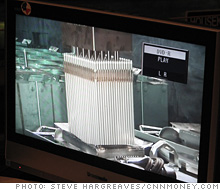

| Spent fuel rods seen through a camera mounted on the pool bottom. Each rod is filled with tiny uranium pellets, and is about the thickness of a pencil. The rods are grouped together in clusters of about 200 to form a fuel assembly, pictured here. |

BAY CITY, Texas�(CNNMoney.com) -- At a Texas power plant, two men in head-to-toe yellow jumpsuits are perched above a pool filled with still, crystal-clear water -- and nearly 20 years worth of nuclear waste.

The 40-feet deep pool, about the size of an Olympic-sized swimming pool, is the current home to thousands of uranium-filled fuel rods -- the radioactive byproducts of a nuclear reactor. The men are using a robotic arm to position the rods sitting at the bottom of the pool.

Pools such as this one are a temporary solution to a very long term problem: the hotly contested debate over what to do with the country's nuclear waste.

Storing nuclear waste on site in pools, or in what's called "dry casks" outside the plant, seems an acceptable solution for the next several decades at existing plants. But nuclear waste remains radioactive for tens of thousands of years, far longer than the manmade pools are likely to survive.

With global warming concerns and rising power demand, the idea of using more nuclear power is gaining traction. The Texas plant is among dozens nationwide that have applied to build more reactors.

But some say a more permanent solution should be found before more new plants are built.

"The industry wants to build now and worry about the waste later," said Edwin Lyman, a senior staff scientist at the Union of Concerned Scientists. But to build "dozens or hundreds of new plants when we don't have any plausible means forward on waste disposable is irresponsible."

Recycling the waste, as the French do, is often held up by lay people and politicians in the United States as a solution to this country's waste problem.

When waste is recycled, the uranium and plutonium can be separated out from used nuclear fuel and fed back into a reactor. Critics hate it because the process of separating out the plutonium enriches the element to something closer to what's needed to build a nuclear bomb. Supporters like it because it reduces the need to go out and mine new uranium for fuel.

But recycling isn't an ironclad solution for waste. It may reduce the amount of high level waste left over -- the French say it reduces it by a factor of eight, but others like Lyman argue it's more like a factor of two. Either way, there is still some waste leftover.

"There's no process that doesn't have waste at the end," said Steven Kraft, senior director of used fuel management at the industry's own Nuclear Energy Institute.

Or as Jonathan Burton, an expert in nuclear waste at the consultancy Accenture, put it, "There's only one solution that's OK, and that's geologic disposal."

Geologic disposal, or burying the stuff deep in the earth, had been the government's plan for decades. Although other methods of disposal were studied -- sending it into outer space, burying it in the polar ice sheets -- storing it in the earth was thought to be the best solution, according to the government's research.

By the early 1980s the government had decided to build a long term storage site for nuclear waste, and began collecting billions of dollars from electric utilities toward that end.

In 1987 it started looking solely at Yucca Mountain, a site on federal land some 90 miles northwest of Las Vegas that was thought to have solid rock formations, essential for containing the waste for long periods of time. In 2002 the government formally designated the site as its repository. Construction has begun, although now it's mostly just series of tunnels into the earth.

But Nevada residents never liked the plan, and were vocal about their opposition. When Harry Reid (D-Nev.) became Senate majority leader in 2006, the site's future came into question. Some critics also pointed to the geology at Yucca Mountain, saying the rocks were more porous than previously thought and noting the volcanic activity in the area.

Although the Nuclear Regulatory Commission is still reviewing the permit to store waste at the site and those in the industry hope it can still be built, the Obama administration now says Yucca Mountain is no longer an option. More than 25 years in the making, and the project seems dead.

Accenture's Burton believes an underground storage facility is still a possibility: "From an engineering perspective, I have every reason to believe one is," he said. Burton said it's prudent to build more plants as long as we're confident another repository can be built.

Energy Department said Secretary Steven Chu will be appointing a blue ribbon panel shortly to figure out what to do with nuclear waste.

That could mean reverting to the previous list of repository candidates, which named at least 10 other sites in states including Maine, Washington, New Mexico and North Carolina. It might also mean the space or polar ice cap idea is back on the table, but the spokesperson declined to comment.

Whatever the case, it shouldn't take another 25 years to reach a solution. ![]()