FORTUNE -- It was the winter of 2006, and EOG Resources executive vice president Kurt Doerr had to be wondering what the heck he was doing prospecting for oil in the frigid central plains of North Dakota. Sure, wildcatters had been pumping modest amounts of crude out there for decades. However, nobody had ever found a true gusher, and the timing seemed odd given that EOG's core business -- drilling for natural gas, not oil -- was absolutely booming. EOG's net income had just doubled, natural-gas prices were fresh off all-time highs, and cutting-edge technologies were opening up vast new gas fields like Barnett Shale in Texas.

Still, Doerr's boss, EOG chief executive Mark Papa, wanted to shift EOG's focus from natural gas toward oil. Even more surprising: Papa intended to drill for oil not in hot spots like Canada, Africa, or the deep water of the Gulf of Mexico, but in the continental U.S. If Doerr had any doubts about his boss's strategy, they were put to rest in May 2006 when EOG drilled its first major North Dakota oil well in Parshall, a tiny outpost about 50 miles west of Minot. As with EOG's Barnett gas wells, the Parshall oil well was drilled horizontally -- in contrast to the vertical wells traditionally drilled in the North Dakota oil patch. Doerr's crew drilled to a depth of 9,100 feet, stopped, and then curved out laterally to target a 40-foot-wide layer of porous, oily rock sandwiched between two thick layers of shale. "Our goal was to drill horizontally 5,000 feet," Doerr recalls during a tour of the original drilling site. "But we only got out 1,800 because of all the oil and gas we encountered."

To Doerr's amazement, the Parshall well immediately produced 450 to 500 barrels a day, about five times more than his best-case scenario going in. "I called up Mark and said, 'Wow, I think we've found something here.'"

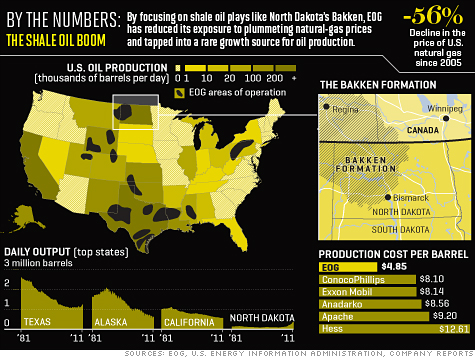

Five years later EOG (EOG, Fortune 500) is the largest oil producer in North Dakota, a state that now trails only Alaska, Texas, and California in onshore oil production. North Dakota production has increased from 95,000 barrels a day in 2005 to 360,000 today and has helped reverse a 20-year decline in domestic oil production. Indeed, the North Dakota oil boom is one reason U.S. oil prices, as measured by West Texas Intermediate Crude, have been running $15 to $20 a barrel cheaper than the Brent crude sold in Europe.

EOG's own production of oil and other liquid hydrocarbons has increased from 35,000 barrels a day in 2005 to 130,000 today, and with new fields coming online, Papa tells Fortune that he expects to be close to 200,000 barrels by 2012. Hitting that number would probably make EOG the second- or third-largest domestic producer in the U.S. "Five years ago we probably didn't even crack the top 50," Papa says.

The key to EOG's success has been technical smarts coupled with shrewd land acquisition. EOG has perfected horizontal-drilling technologies that, when combined with hydraulic fracturing, have opened up gas and oil reservoirs others once deemed too difficult or expensive to explore. The company's challenge going forward will be proving that the drilling techniques perfected in North Dakota can be applied with similar success to other North American shale oil formations -- and eventually to shales abroad. Moreover, with Papa nearing his 65th birthday and his second-in-command having just retired, new questions are emerging about whether EOG could wind up as a takeover candidate, much as onetime rival XTO Energy did a couple of years back.

The big switch to shale

The company made its debut on the Fortune 500 in 2009 at No. 350, with $7.1 billion in prior-year revenues. (As with most oil and gas companies, corporate revenues are closely tied to prevailing energy prices.) In 2011 the company checked in at No. 377, with $6.1 billion in sales. Fortune 500 rankings aside, the trajectory for EOG has been very much upward. EOG's earnings rose 17% in the first quarter, and its stock price has more than doubled since bottoming out at a recession low of $50 a share in February 2009. The company's balance sheet is also swimming in cash, with $1.67 billion at the end of March, up from $686 million at year-end 2009.

EOG's gas production, once the company's hallmark, has been flat at around 1.65 billion cubic feet per day, but that is by design. Spun off from Enron in 1999 (original name: Enron Oil & Gas), EOG was primarily a natural-gas producer during its early years and was one of the winners in Texas's Barnett Shale. To produce gas in the Barnett, EOG utilized horizontal drilling in combination with hydraulic fracturing, or "fracking," which involves pumping pressurized water into underground rock layers, creating fissures through which gas can flow.

(Though fracking has been around since the 1940s, the technique has become controversial lately, particularly among East Coast environmentalists who fear groundwater contamination from the drilling of gas wells in Pennsylvania's and New York's Marcellus Shale. EOG has a small operation in the Marcellus, and for his part, Papa -- citing a study by the Ground Water Protection Council, an organization of state water-quality regulators -- maintains that there has yet to be a single documented case of underground drinking-water aquifers contaminated by fracking.)

Over time EOG's chief began to worry that horizontal drilling was proving too successful. An engineer by training, Papa, 64, calculated that the quantity of new gas likely to be extracted from all the new shale gas plays like Barnett and Louisiana's Haynesville would saturate the market. Unlike oil, natural gas cannot be easily transported to overseas markets where prices may be higher. Indeed, since 2005, U.S. natural-gas production has increased 33%, and the price of natural gas has fallen from $9 to $4 per thousand cubic feet. "Our company had been built on an assumption that North American gas production was in inexorable decline and that gas prices would continue to rise. It took us about a year to recognize that the whole paradigm had changed."

Papa figured he had two options. He could sell the company before everyone else realized gas prices were about to crater -- which is basically what XTO did when it sold to Exxon Mobil (XOM, Fortune 500). Or he could listen to the EOG geologists and engineers who kept telling him that the same techniques EOG was using to produce gas from shale would work for oil too. He chose the latter, instructing his scientists to scour 70 years of North American drilling data and compile a list of shale formations where oil had once been found. "Maybe there's a company that drilled a well back in 1950," he explains, "and it found a shale containing oil but abandoned the well because there was no technology to access the oil."

EOG's scientists correctly identified North Dakota's Bakken Shale as the formation with the most oil potential. There was nothing lucky about EOG's determination, says Tim Parker, manager of T. Rowe Price's New Era Fund and a longtime EOG shareholder. "EOG is an engineering-driven company, and its great gift is identifying these plays early," says Parker.

Despite EOG's reputation for technical know-how, Wall Street investors were skeptical when Papa explained his plan to focus on extracting oil from shale as opposed to gas. The conventional wisdom back then was that oil molecules were simply too large to slip through fissures created by fracking. Papa tried to convince money managers that the fissures were in fact large enough for oil to flow and could be held open by grains of sand -- pumped into the rock with fracking water -- that acted like tiny ball bearings. "One guy said to me, 'Mark, you've got a good reputation on Wall Street as a credible person. But about six or seven of your peer companies have been in here in recent months, and they've all said EOG is barking up the wrong tree.'"

The dubious bet pays off

This "wall of disbelief" -- Papa's term -- did have one benefit. It allowed EOG to acquire mineral rights at bargain-basement prices, even after the cloak of secrecy surrounding the Parshall discovery had lifted. EOG holds 600,000 acres in North Dakota, leased at an average cost of $190 an acre, and another 595,000 acres in Texas's Eagle Ford Shale at a cost of around $450 an acre. Similar properties in the Bakken are now leasing for anywhere from $800 to $6,000, according to Papa, while Eagle Ford acreage goes for as much as $20,000. Papa believes Bakken and Eagle Ford will wind up as the fifth- and sixth-largest oilfields ever discovered in the U.S., each with about 4 billion barrels in recoverable reserves. To put that into perspective, the largest offshore oilfield, Gulf of Mexico's Thunder Horse, is expected to produce 1.2 billion barrels, and drilling offshore is more expensive. "It was pretty darn uncanny for them to sneak in and carpet-bomb all that acreage," says Parker.

The challenge for EOG going forward will be replicating its North Dakota success elsewhere. Papa maintains that 70% of what his crews learned in the Bakken can be applied to the Eagle Ford and other shale oilfields where EOG has acquired land, such as New Mexico's Leonard Shale, West Texas's Wolfcamp, and Colorado and Wyoming's Niobrara. "Our learning curve is now months rather than years," he says.

Analysts seem impressed. EOG's Eagle Ford operation has grown "from zero to 23,000 [barrels per day] of oil in less than 18 months," gushes Wunderlich Securities oil analyst Irene Hass in a recent report. She thinks Eagle Ford will surpass Bakken as EOG's top oilfield by 2013. One obstacle is the high cost of drilling. Rigs are scarce, and workers are in such demand that North Dakota roughnecks are earning $60,000 a couple of years out of high school, according to Frank Mosely, an energy economics professor at Minot State University. Another bottleneck is transportation. The cost of accessing existing pipelines is so high that EOG is able to save in the range of $5 to $10 a barrel by moving oil by rail rather than by pipeline.

Needing capital to fund its new drilling, EOG has raised $1.5 billion since late last year by issuing new stock and selling off some older gas fields. The stock sale didn't thrill Wall Street, as some analysts would have preferred that EOG borrow money rather than dilute existing shares. Papa, however, has always managed EOG's balance sheet conservatively -- understandable given the company's old link to Enron -- and he didn't want to take EOG's debt-to-capital ratio above 30%.

Beyond Bakken

What's next for EOG? Papa believes there are many yet-to-be-discovered shale oil plays in other parts of the world. One well-connected EOG shareholder tells Fortune that EOG has formed a partnership with YPF, Argentina's largest energy company, to develop a "very large shale oil deposit" in that country. A YPF spokesman confirmed the existence of a relationship with EOG, and EOG disclosed in June that it has taken a position in some shale oil acreage in Argentina.

With EOG stock up 16% this year to $106 a share, Papa nearing his 65th birthday, and second-in-command Loren Leiker having just announced his retirement, there's now some speculation that the company could be sold. As Goldman Sachs analyst Brian Singer put it delicately, Leiker's retirement will "raise questions" about whether EOG will "look toward consolidation" when Papa himself retires.

Papa dismisses any buyout talk. "I tell our shareholders and our prospective shareholders, 'Don't buy us as a possible takeout candidate,' " he says. "Why would we actively try to sell this company when we have all this growth ahead of us -- in a commodity trading at $110 a barrel?"

--Jon Birger is a regular Fortune contributor specializing in energy and investing topics.